1 “Sarcophagus of the Spouses” Etruscan Terracotta Couple, Louvre, ca. 510 BCE (Photo P. Hunt, 2025)

By Patrick Hunt –

One of the most fascinating cultures of the ancient Mediterranean is the Etruscan world. This culture is well-represented in major global museums, and the better the museum, the better represented are the Etruscans in the major collections. I offer here a few brief thoughts on a few of the singularities of Etruscan material culture.

I am certainly not alone having visited and studied the Etruscans and their extant material culture in at least a dozen museums many times with major collections in separate galleries devoted otherwise to the Etruscans, as well as spent years examining the major sites and some minor sites across Tuscany and Umbria. Over the years I have noted a few Etruscan cultural hallmarks that in some ways are almost unique to them. This seeming singularity can be deduced in first looking at museum collections of representative materials and then Etruscan sites, although I will be very selective in this brief Etruscan survey and show only a few museum objects or site images.

2 Glyptothek Museum – Antike am Königsplatz, Munich (Photo P. Hunt 2016)

First, these major museums with Etruscan collections include not only the British Museum (over 2500 Etruscan objects), the Musée du Louvre, (over 10,000 Etruscan objects) the Vatican collections (especially Museo Gregoriano Etrusco) with a collection ranging between 15,000 to 50,000 Etruscan objects; 4000 objects on display, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (over 1000 Etruscan objects), the Altes Museum in Berlin, the Glyptothek Museum – Antike am Königsplatz in Munich, the State Hermitage Museum of St. Petersburg (over 400 major Etruscan objects)), and of course the Museo Nazionale Villa Giulia (National Etruscan Museum) in Rome (over 6000 Etruscan objects). Then there are also the superb Italian regional museums of Tuscany and Umbria such as the National Archaeological Museum of Florence (Museo Archeologico Nazionale Firenze), the Archaeological Museum of Cortona (Museo dell’ Accademia Etrusca e della Citta di Cortona), the National Archaeological Museum of Tarquinia (Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Tarquinia), the National Archaeological Museum of Orvieto (Museo Archaeologico Nazionale di Orvieto), the Etruscan Museum Guarnacci of Volterra (Museo Etrusco Guarnacci), the National Archaeological Museum of Chiusi (Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Chiusi), the National Archaeological Museum of Cerveteri (Museo Nazionale Cerite), the Fiesole Archaeology Museum (Museo Civico Archeologico di Fiesole), and the Etruscan Museum of Vulci (Museo Nazionale di Vulci) to name but a few regional Etruscan collections in Italy. These Etruscan study visits do not even include the many site visits over decades – including to major necropoli like Monterozzi of Tarquinia, Banditaccia of Cerveteri, and Crocifisso del Tufo of Orvieto – to the twelve city state sites of the Etruscan League and many other smaller sites.

When you visit any of these Etruscan museums or collections, what are some of the obvious yet striking things about Etruscan culture you immediately notice most in these museums? What range of Etruscan objects and materials may be different than in other ancient cultures?

These museum collections of Etruscan objects fairly precisely reflect the material culture that has been amassed from rich tombs and necropoli, even though these necropoli and their individual tombs have been almost entirely depleted for a few centuries. This is true as well of Tarquinia except that its Monterozzi Necropolis underground tombs’ walls have the best-preserved Etruscan wall paintings of all Etruscan art, numbering several hundred mesmerizing vignettes in varying states of visibility and access.

3 Terracotta Architectural Detail of Temple Roof Pediment and cornices, Villa Giulia 6th c. BCE (reconst.) (Photo P. Hunt 2014)

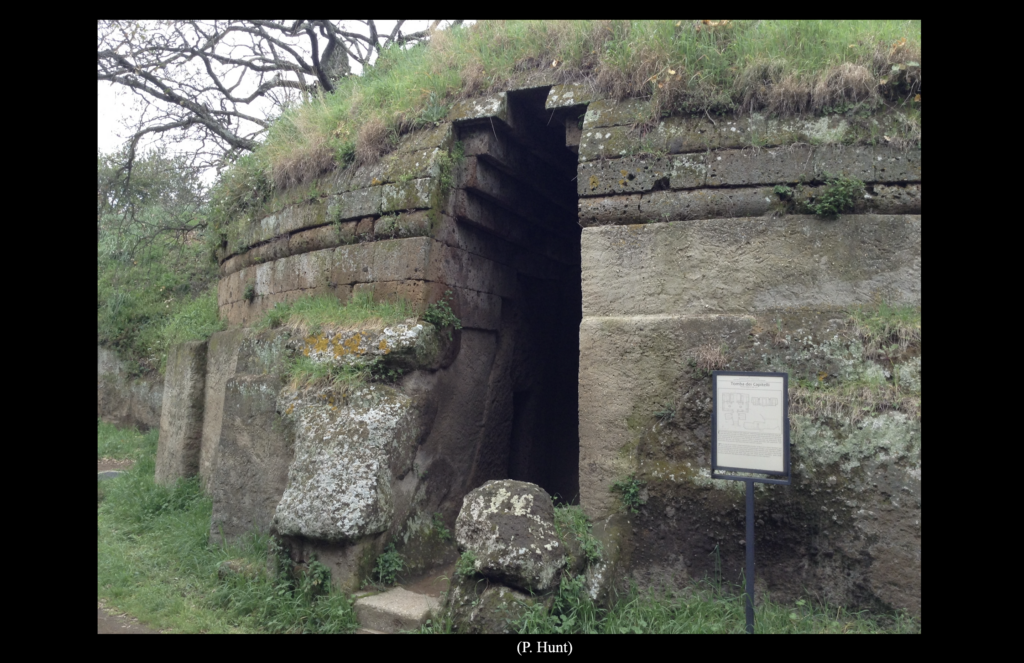

4 Tomba dei Capitelli, Banditaccia Necropolis Cerveteri, tufa blocks, ca. early 6th c. BCE (Photo P. Hunt 2014)

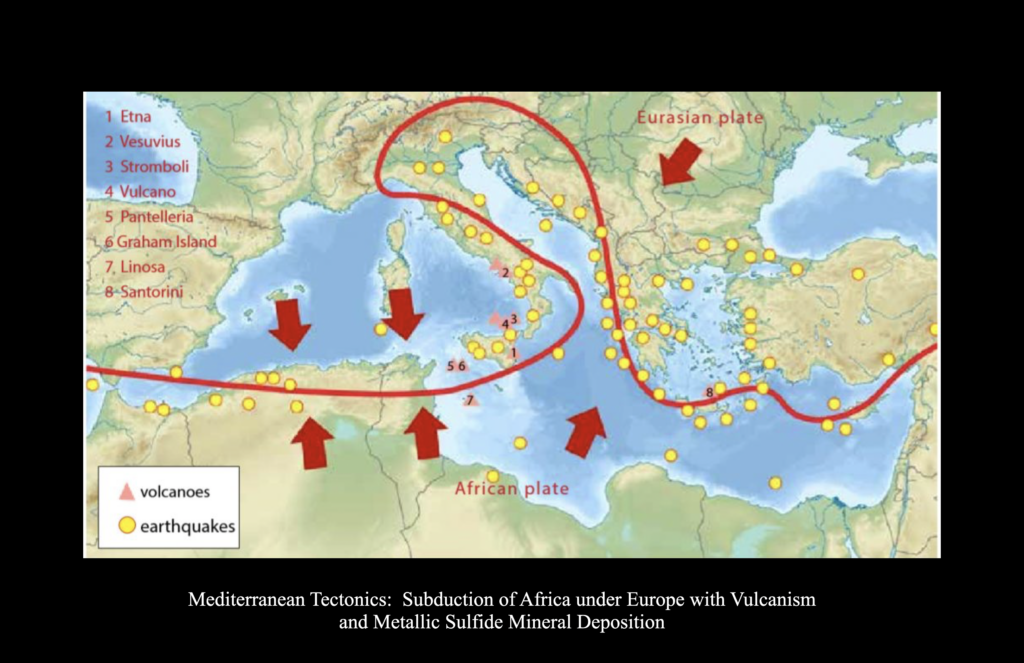

First, the majority of Etruscan sculpture in these collections is mostly ceramic (terracotta is fired pottery from “burnt earth”) or bronze instead of stone. Many Etruscan sarcophagi are ceramic, some are also carved from tufa and some are carved of Volterra alabaster, all of this material local to Italy. Unfortunately, there isn’t space in this brief article to go into detail of any one object. This Etruscan preponderance of terracotta or ceramic sculptures is partly because there is not much stone similar to what Greece and Rome utilized, since the geology of what Etruscans had available was mostly tufa – either soft and porous volcanic ash or similar soft sedimentary stone (e.g., note Fig. 4 above, Banditaccia Cerveteri necropolis Tomba dei Capitelli constructed of tufa blocks) – whereas the Greeks and Romans had enormous deposits of limestone and marble available to them, although Rome also extensively used volcanic tufa around the city of Rome. This phenomenon of Etruscan stone can be understood in Northern Italy as a consequence of plate tectonics, where the continent of Africa is a convergent plate pushing against Europe and subducting under it, and where the Aeolian peninsula of Italy was thus high in igneous and volcanic activity on its western coast (see Fig. 5 Italian map below on Mediterranean Tectonics). This subducting plate also ripped apart the crust of the northern Mediterranean and left remnant jagged peninsulae like Italy and the Balkans in its slow but inexorable action on the earth’s crust here.

5 Map: Tectonic Geography and Geology of the Mediterranean (Image public domain)

One immediate consequence of the volume of igneous activity is not only the thick but workable tufa – often made of compressed volcanic ash – that covers much of Tuscany and Umbria, but also a high volume of sulfide metallic deposits like copper, gold, lead, zinc, iron and tin, providing the Etruscans with an enormous mining opportunity to make bronze by alloying copper and tin and even brass by alloying copper and zinc, an alloy in which they pioneered a different metallurgy than many other cultures. Few ancient cultures had such wealth of both copper and tin for bronze as well as gold and other metals. [1] Old volcanic calderas like Lago Bolsena and the volcano of Monte Amiata are just a few examples of this geology.[2] Note the Monte Amiata volcano (triangulated between Siena, Montalcino and Grossetto in the Maremma region of Tuscany) isn’t on this above map (Fig. 5) but is close to the coast opposite Corsica. Sulfur and mercury sulfide (HgS) from this “sacred” volcano known to the Etruscans were used in many Etruscan wallpaintings; the red mercury sulfide is known as the pigment cinnabar. Eerily, both cinnabar and sulfur are slightly fluorescent as well, which can be seen in dim light even in tombs like the Tomba dell’Orco in Tarquinia and the Tomba della Scimmia (Chiusi); there are still many modern mercury mines on Monte Amiata.

The wealth of the Etruscans can be partly seen in a vast array of bronze objects, whether ornaments and votives or sculpture. Greeks like Pindar (6th-5th c. BCE) and Strabo (1st c. BCE-1st c. CE) and later 1st c. CE Romans like Pliny (esp. Nat. Hist. 34-35) praised Etruscan bronze production in style and scale with colossal figures up to 50 ft high, many bronzes so highly-valued that the Romans looted 2000 bronze statues from Etruscan Orvieto (Velzna-Volsinna) in 264 BCE, most likely to melt down for coins and weapons. The recently-discovered 24 mostly intact Etruscan bronzes from the San Casciano dei Bagni baths are a stunning reminder of how many Etruscan bronzes must have existed. [3]

6 Monteleone Bronze Chariot Metropolitan Museum of Art New York. Mid-6th c. BCE (Photo P. Hunt 2025)

7 Piacenza Bronze Liver Model , ca. 2nd c. BCE, Museo Civici di Palazzo Farnese, Piacenza (Photo P. Hunt 2025)

The abundance of a range of Etruscan gold jewelry is also understandably dramatic. The Etruscan high volume of gold deposits also enabled them to excel in making jewelry, perhaps more than almost any other contemporary ancient culture in Europe and so voluminous that the Romans to the south who followed them were jealous, making sumptuary laws in Rome banning excessive jewelry that both Etruscan men and commonly wore. The copper of Etruria – was accessed for many millennia long before the Etruscans, even in the Copper Age since we know the ore for Ötzi the Iceman’s palgrave (unperforated axe) and other axes around Italy and the Aps also from around 5000 years ago derives from these same Colline Metallifere (“Metal-Bearing Hills”). One other evidence of this rich metal-bearing region is that the coastal town of Piombino means “Leadville” from Latin plumbum.

8 Terracotta Lifesize Apollo of Portonaccia (Veii), ca. 510 BCE, Villa Giulia (Photo P. Hunt 2014)

Another fascinating aspect of why so much rich Etruscan grave goods survived is because the Romans were superstitious about desecrating funerary places, fearful of the gods’ retribution since the Romans practically borrowed in entirety the intricate and pervasive Etruscan system of divination and omens they called the Disciplina Etrusca.[4].

Last but not least, because their tombs were dug out of tufa rock rather than merely buried in the ground as in Greece where seismic activity often crushed the grave goods, the best and highest quantity of preserved Greek ceramic objects – both Archaic black and Classical red-figure – was found in Italy, not Greece, especially in Etruscan necropoli like Vulci, Cerveteri and other sites mainly explored in the past few centuries. Even though the urban site of Vulci is still only about 5% excavated, new temples are being discovered and excavated from the 1950’s to the present (Vulci Cityscape Project 2020 on).

9 Satyr Rhyton, 4th c. BCE, Glyptothek Munich (Photo P. Hunt 2016)

10 Caeretan Hydria of Herakles, Kerberos and Eurystheus, ca. 525 BCE, Louvre (Photo P. Hunt 2025)

In Etruscan museums, one can also note a general equality of Etruscan women, many viewed on their own sarcophagi with their names inscribed. We can also easily observe the intimacy between men and women in the material representations of couples depicted on the ceramic our terracotta sarcophagi or urns in museums like Villa Giulia, the Louvre (see Fig. 1 above, “Sarcophagus of the Spouses”, Terracotta Couple, Louvre) or the Elderly Couple (Urna deli Sposi) of Volterra 1st c. BCE (Museo Etrusco Guarnacci).

11 Urna degli Sposi (Elderly Couple) 1st c. BCE in Museo Etrusco Guarnacci (image in public domain)

This intimacy and affection shown is contrary to Roman mores codified in laws that often forbade public display of affection and at times bemoaned the egalitarian status of Etruscan women compared to Roman matrons.

12 Gold Pendant of Achelous with pulviscula granulation, 6th-5th c. BCE, Louvre (Photo P. Hunt 2025)

13 Gold Jewelry “Grappolo” (grape cluster) earrings, 4th-3rd c. BCE Met. Mus. NY (Photo P. Hunt, 2025)

Overall then, what stands out in Etruscan collections is not only the abundance of Etruscan ceramic (or terracotta) sculptures and pottery rather than primarily stone – and also blackware bucchero pottery – mixed with imported Greek pottery. Then add in the astonishing volume of surviving bronzes from tombs relative to Greek and Roman bronze (which was so often melted down as they needed to recycle), which suggests the Etruscans not only had a higher volume of bronze to begin with, since they had both enormous copper and tin deposits, but also that the Etruscans didn’t need to recycle bronze because it was so commonly available. While the Etruscans did also build with tufa, much of their architectural detail was also rendered in terracotta. Plus, we are amazed when we view the stunningly-rich gold jewelry (using techniques of repoussé, molds, filigree, granulation, and a special granulation so small it’s called pulviscula or “powder”; hardly visible to the naked eye – note the Achelous pendant beard above in Fig. 10). This gold jewelry was found prolifically in Etruscan tombs (often along with imported amber from the Balkans) and the jewelry is also depicted in relief on the sculpture, so it becomes clear how incredibly wealthy the Etruscans were (and what survived partly thanks to Roman superstition and tufa necropoli). All this adds up to represent an ancient culture so blessed by nature partly due to its geographical context along the Tyrrhenian coast where vulcanism and igneous geology provided tufa and a wealth of precious metal to make bronze materials and a gold jewelry seemingly unsurpassed in antiquity.

Notes and References:

[1] Emeline Richardson, The Etruscans: Their Art and Civilization. University of Chicago Press, 1976 ed.; Ellen Macnamara. The Etruscans.Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991, 5.

[2] L. Vezzoli, C. Principe. “Monte Amiata Volcano (Tuscany, Italy) in the History of Volcanology, Part I. Earth Sciences History 39.1 (2020) 28-63; also see A. Sodo, D. Artioli, A.Botti et al. “The colours of Etruscan painting: a study on the Tomba dell’Orco in the necropolis of Tarquinia.” Journal of Raman Spectroscopy 39.8 (2008) 1035-41.

[3] James-Simon-Galerie, “The Bronzes of San Casciano dei Bagni: A Sensation from the Mud” Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, May 2025 (https://www.smb.museum/en/exhibitions/detail/the-bronzes-of-san-casciano-dei-bagni/).

[4] P. Hunt and P. Luna. “Reading Livers Through Reading Literature: Hepatoscopy and Haruspicy…” Stanford Archaeolog 2007 (courtesy M. Shanks) (https://web.stanford.edu/group/archaeolog/cgi-bin/archaeolog/2007/09/28/reading-livers-through-reading-literature-hepatoscopy-and-haruspicy-in-iliad-20469-ff-24212-ff-aeneid-460-ff-10-175-ff-cicero-and-pliny-on-divination-among-others/).