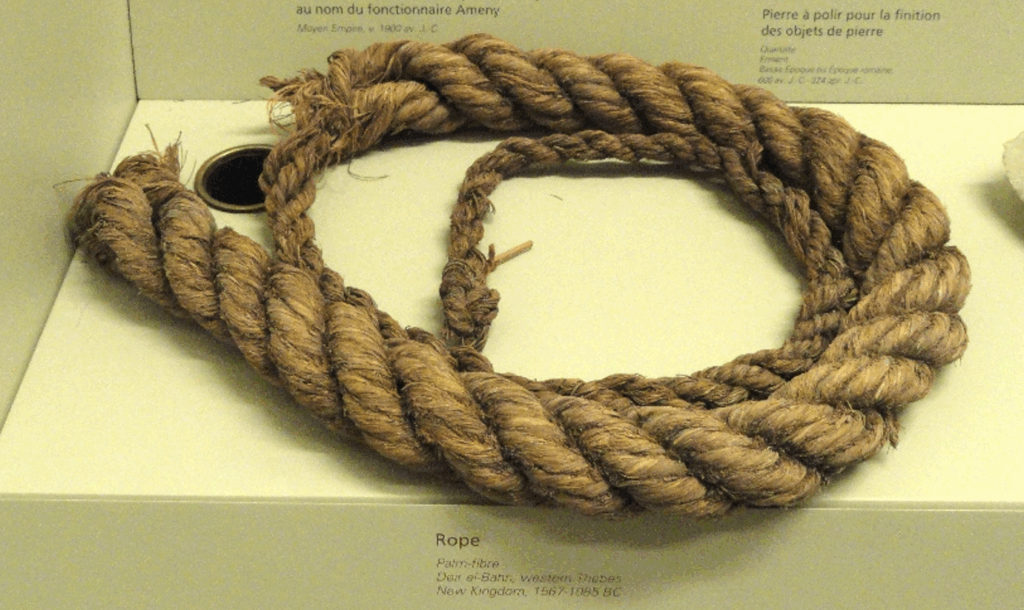

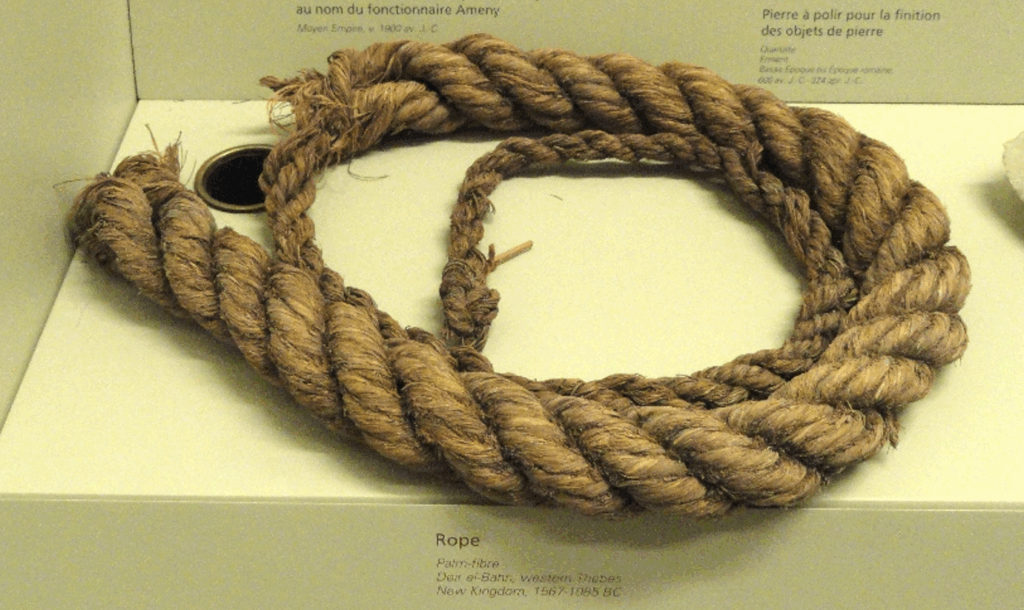

Three-strand rope of palm fiber exhibited in the Royal Ontario Museum, from Deir-el-Bahri, New Kingdom (ca. 1567-1085 BCE) Image public domain

By Garth C. Hall –

Ropes (more generally, “cordage”) were critically important tools in Egypt’s ancient progression through the pre-Dynasty period all the way to modern times. The artistry of cordage production is closely associated with the widespread artistry of fabric weaving — they both represent a spectrum of fiber selection, fiber processing, and twisting or weaving. The specialty of rope making utilized fiber for tying or pulling large and/or heavy objects where strength was required.

1 Fourth Dynasty (Old Kingdom, ca. 2500 BCE) rope discovered with the Khufu ceremonial ship at Giza. Image by Jon Bodsworth, image in public domain

Over millennia before the common era, communities across the globe created multiple methods of tying things together for specific purposes. Plant fibers were used frequently, if not predominantly, as alternatives to animal hair, hide strips or sinew. A question explored by some archaeologists is how far back in time did humans (or other hominins) develop uses of plant fiber for cordage (apart from uses for clothing or decorative weavings)? Archaeological work, for example at Abri du Maras cave in France (Hardy, et al, 2013) identified unnaturally twisted fibers among a wide variety of lithic, bone and other remains dated (based on bone analysis) at 91-72 thousand years before present (91-72 kya). The authors point out that more work and analysis is needed before definitive conclusions can be reached about the source of fiber found and the purposes of its use.

From a much later date, ca. 3300 BCE, shoes from the well publicized and documented Alpine “Ice man” discovery also known as ‘Oetzi’ reveal use of twisted plant fiber twine from linden (Tilea sp.) tree bast, although clearly less than a centimeter in width. (Fleckinger, 2011). These are also the oldest shoes ever found to date.

2 Oetzi Shoe interior of linden tree bast fiber Iceman Database (https://www.iceman.it/en/oetzi/the-iceman, Illustration courtesy of South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology

Plant fibers almost always decay rapidly except in rare circumstances such as in the Oetzi discovery. Very few findings of pre-common-era cordage are available to be examined today. In contrast, ancient woven cloth using plant fiber are relatively common discoveries associated with burials in some locations — for example linen wraps associated with mummies in Egyptian Dynasty-era tombs.

Fundamental Questions

This paper focus on Egyptian ropes and seeks to answer a few fundamental questions:

- Given that ropes were important in ship building and operation, were ropes also of critical importance in construction of pyramids, tombs and monuments?

- Did the Egyptians benefit from learnings or products developed elsewhere?

- What do we know about the materials used and their qualities?

- What were the methods of rope-making?

- Did ropes have any ceremonial or religious value?

Nautical Use

A clear incentive for rope usage (for trade and naval purposes) was finding ways to tie masts and sails to capture wind energy, as opposed to relying only on human rowing energy.

Well beyond Egypt, cordage was important to ancient seafaring communities around the Mediterranean. In contrast, seafaring in East Asian seas (Schottenhammer, 2012) occurred later, with ship building beginning in the Han Dynasty (ca. 202 BCE-220 CE). Boat building and operation for trading is perhaps the prime example where cordage enabled progress. Operating ocean-going vessels would arguably have been feasible without cordage but clearly having the means to tie and flexibly orientate sails to changing winds advanced the practice immeasurably.

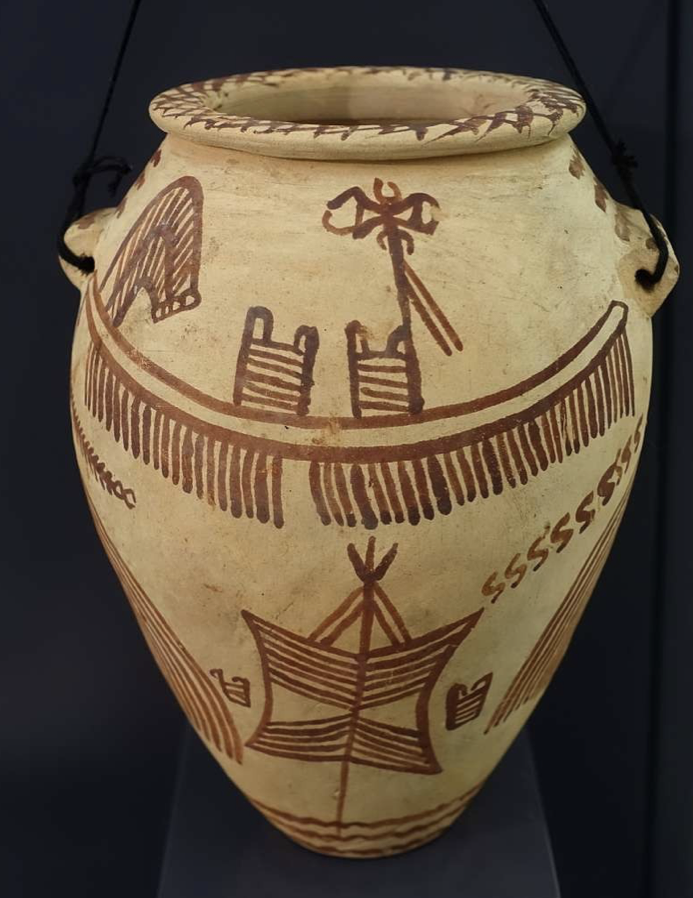

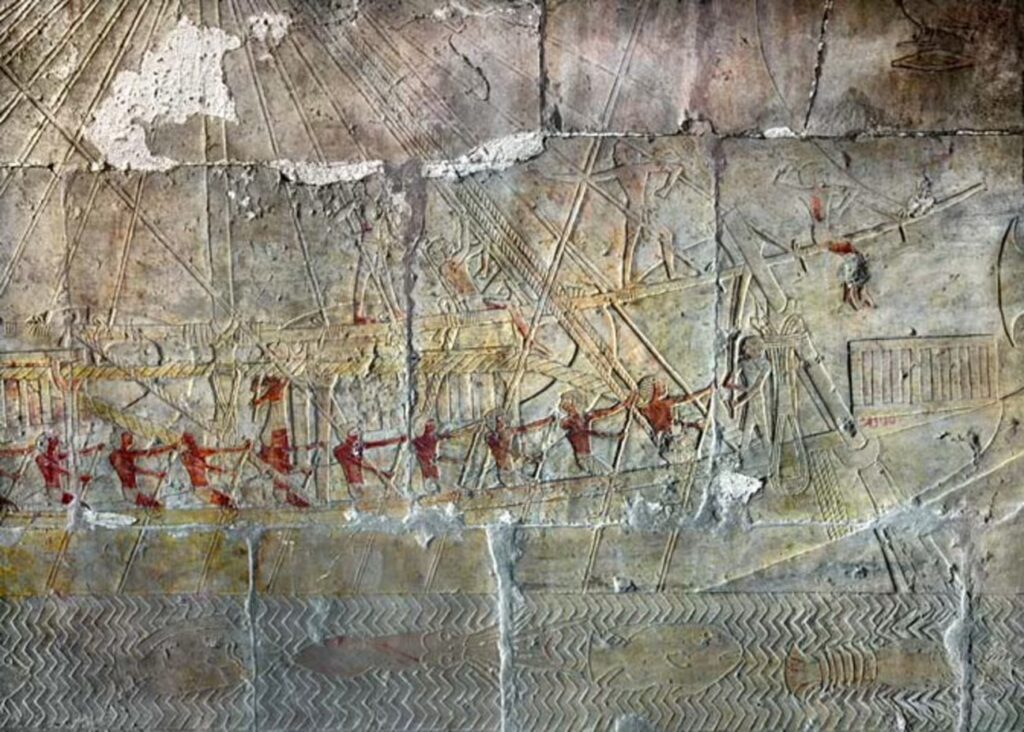

Evidence from depictions of boats such as that in Hatshepsut’s Deir el-Bahri funerary monument (constructed ca. 1478-1464 BCE) confirms the principle securing masts with ropes for fixing sails. Perhaps the most dependable “date-stamps” of sail usage on ancient boats come from depictions on contemporary pottery.Mark (2013) considered scenarios of sailing chronology from multiple sources and concluded, at least in the context of ancient Egypt, use of sails likely began in the Nagada-II era, in Predynastic Egypt.

3 Vase from a grave of the Nagada-II culture, Egypt, El-Amra, ca. 3500-3200 BCE. Marl ceramic, H 90. DSC05332, Martin von Wagner Museum -Würzburg, Germany

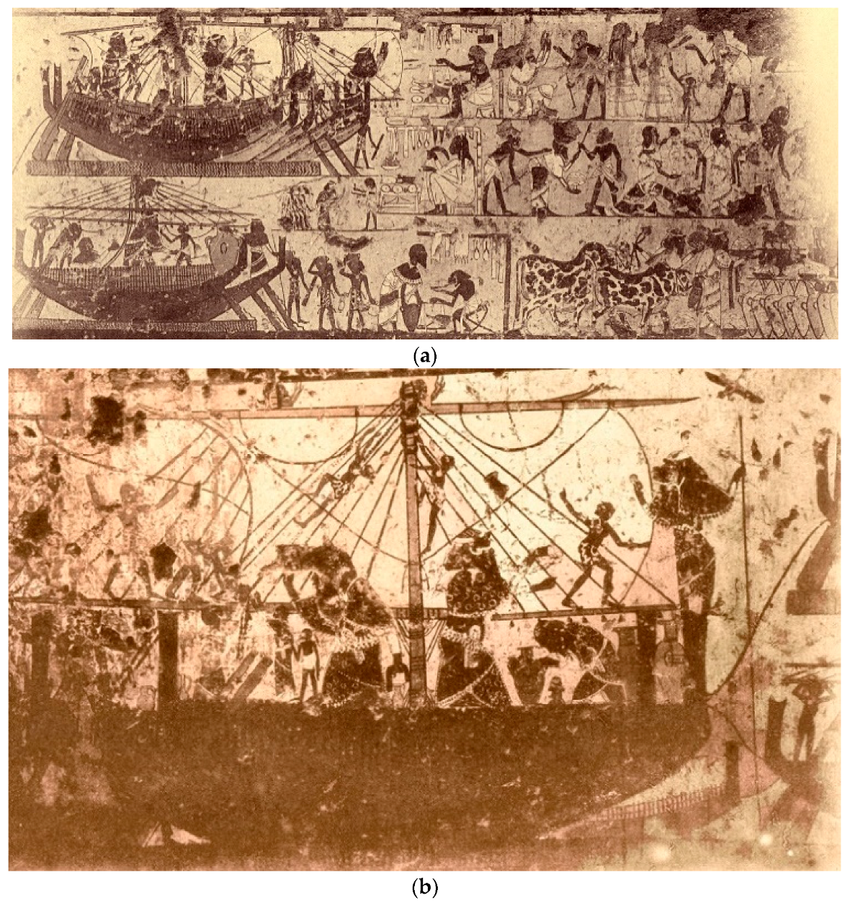

Beyond Egypt, but certainly within its trading orbit, two notable Mediterranean shipwrecks illustrate the time span of early trading by boats using, at least in part, wind energy. One is the ca. 1300 BCE Uluburun wreck, off southern Turkey. Pulak (2008) studied the wreck extensively and, among other results, portrayed a reconstruction of the boat including timber configuration, mast and yards (horizontal members for sail support), and undertook a detailed cargo analysis. Based on cargo analysis, among other observations, Pulak hypothesizes that the route of this boat may have included anchorages in Greece and Egypt. Pulak’s article above includes a drawing of Syrian boats, (a) plus (b) closeup below, with sails as well as oars, based on paintings in the tomb of Kenamun (Theban Tomb 162) at the time of pharaoh Amenhotep III, who ruled from ca. 1391-1353 BCE.

4 Paintings of Syro-Canaanite ships in the tomb of Kenamun (TT 162) at the time of pharaoh Amenhotep III, who ruled from ca. 1391-1353 BCE (courtesy of Shelley Wachsmann, 2019)

The second Mediterranean example is reportedly the oldest Black Sea intact shipwreck, dated to ca. 400 BCE (University of Southampton, 2018). Images of this intact wreck (lying in very deep water) by University’s Black Sea Maritime Project show rowing decks, rudder and mast.

Discoveries (Ward, 2012) of ancient cedar ships at former harbor sites along Egypt’s Red Sea coast date back as early as the Old Kingdom (ca 2494-2345 BCE) and support a narrative of ongoing nautical trading journeys southwards to the land of Punt, an area which is believed to be in the region of today’s Eritrea. Two large rudders and a number of stone anchors were among the discoveries at the ancient Medi/Wadi Gawasis harbors. Proximate discoveries include several stellae inscribed with Middle Kingdom hieroglyphs and, in nearby caves, a spectacular pile of ropes (described below as “Red Sea ropes”). Inscriptions on the stellae and on ancient cargo boxes discovered in these caves confirm trading voyages to Punt.

Mark (2013) hypothesized that Egyptian Red Sea voyages began later than their initial Mediterranean voyages. In the absence of specific archaeological discoveries to pin down relative dates of voyaging in these two spheres, Mark observes that Mediterranean voyages were less treacherous than Red Sea voyages, which were challenged by unmapped coral reefs, changeable winds and sandstorms. However, ultimately the rewards of southerly trading connections with led to considerable nautical trade in the Red Sea in the Middle Kingdom and later (Ward, 2012).

It seems likely that pre-Dynasty and Dynasty-era Egyptian sailors encountered sailors from other lands in both the Mediterranean and the Red Sea. As mentioned above, ancient shipwrecks in the Mediterranean and Black Sea, as well as depictions of Syrian boats, suggest opportunity for Egyptian sailors to influence others, and vice versa. The same may be said of sailors in the Red Sea, especially involving predecessors of dhow-type boats. Ropes and sails may have been critical technology enabling nautical trading.

Ward (ibid.) points to the use of ropes in boat construction and well as in boat operation — tying sails to yards — and for use with stone anchors. The theory of boat construction expounded by Ward and other authors involves partial assembly at sites along the Nile and transport of sections overland for (re)assembly at docks on the Red Sea. Notre the image below from Hatshepsut’s Funerary Monument of the Voyage to Punt, a boat well-arrayed with ropes for the sails on sea-going Red Sea vessel.

5 Representation of ocean-going ships illustrating use of oars as well as rope ties for masts — from Hatshepsut’s Deir el-Bahri funerary monument. (courtesy Maritime History Podcast 009 and Cheryl Ward, British Museum, 2012).

Studies by Borojevic and Mountain (2013) using thin-section microscope images and scanning electron micrographs from the Red Sea ropes led to the conclusion that they were made papyrus, contradicting earlier studies by others indicating they appeared to be made of reed. One of the three-stranded papyrus ropes photographed in one of the caves appears (from a placed penknife for scale reference) to be approximately 5 cm in diameter. These two authors also concluded that the Red Sea rope samples closely resemble Middle Kingdom (2055-1650 BCE) papyrus rope found at Deir el-Bersha on the Nile and New Kingdom papyrus rope found at Deir el-Bahri, also on the Nile. Since papyrus is known to have grown along the Nile River, especially in the delta, not in the Red Sea area, the authors believe that the Red Sea ropes were sourced and woven in locations along the Nile and transported overland to harbors on the Red Sea.

Uses in Pyramid and Tomb Construction

Numerous books, papers, and videos have been published on methods of pyramid construction. The sources of rock used in construction of tomb burials (above and below ground level) are relatively well known and engender limited controversy. Use of quarried limestone and other locally available rock for bulk structures in ancient construction was prevalent. Sourcing and shaping of limestone blocks used for pyramid facing, from sites such as the Tura caves near Cairo, is well documented. Less prevalent but clearly important for construction of the sacred entryways and tomb chambers was use of igneous rock such as Aswan granite. In the latter case, quarrying, transportation and placement of granite blocks was particularly significant due to hardness of the rock, distances of transportation, and the fact that these blocks were usually much larger and heavier than other stones typically used in bulk construction. However, surprisingly little is known unequivocally about the methods and tools used to transport, lift and place quarried stones. Ramp construction along with use of sleds and rolling timbers, use of levers, and use of ropes are identified as likely methods in many publications. For example, Moores (2019) posits a range of illustrations and theories on feasible methods and tools.

In pyramid and tomb construction, direct evidence of rope usage is sparse in comparison with the rich documentation showing that ropes played an important role in boat manufacturing and operation. The fact that fiber ropes decay over time except when left in exceptionally dry or anoxic conditions leave us with few tangible remnants.

As an indication that ropes were used in pyramid construction, one important piece of evidence is presented by Hassan (1960), who reports on two Aswan granite “pulleys” located in excavations at Giza in 1932-35, each with length 24 cm and width 18 cm. His photographs of one of these items shows three smooth side-by-side grooves over which he understands ropes were passed. The pulleys were not full wheels, as modern day metal pulleys are manufactured, but rather a curved form that would redirect ropes pulled around roughly a quarter circle. Based on Hassan’s image of one of these Giza “pulleys”, its use must have been limited to ropes less than 6 cm in diameter to fit within the grooves.

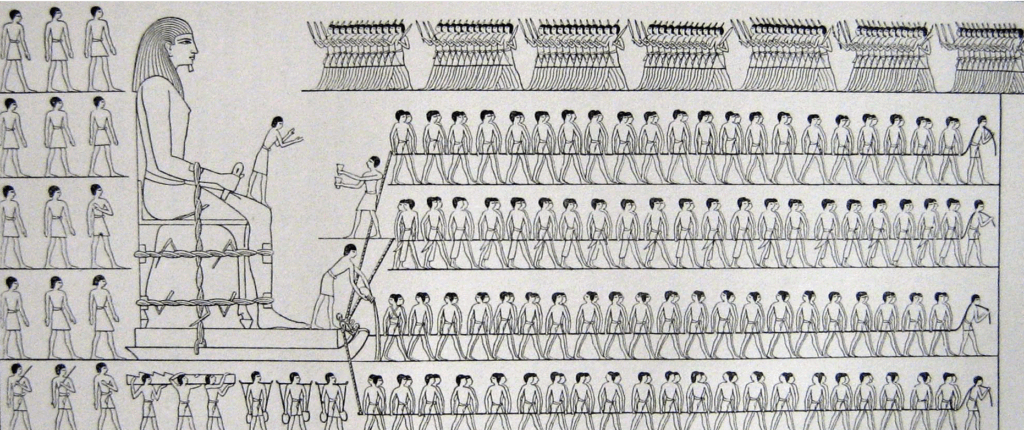

Some tomb painting and carvings are strongly suggestive of rope usage, although it is difficult to know the degree to which these depictions are realistic, symbolic or aspirational. The following drawing from a painting in Djehutihotep’s tomb (ca. 1880 BCE) shows rope usage, not only for securing the statue but also for sled traction. Of further interest is the depicted use of water poured on sand ahead of the sled to reduce friction.

6 Drawing of a painting in Djehutihotep’s tomb (ca. 1880 BCE) image in public domain

Discoveries of Ptolemaic era papyrus rope in the Tura Caves (ancient stone quarries) on the outskirts of Cairo are documented. Lucas and Harris (2012)[1] report that in1942 seven papyrus ropes were found in one of the Tura caves: [“… consisted of three strands, each of which had about forty yarns and each yarn about seven fibres. The circumference was about eight inches and the diameter about two and a half inches.”]

7 Tura Rope section in the British Museum (item EA64397). Attributed to Graeco-Roman Period. Author’s photograph, 2025.

These authors further report that in 1944 in another of the Tura caves a further rope of papyrus was found [“… which was about half the thickness of the previous one, with two strands, eight yarns per strand and three fibres per yarn.”] Barker and Mackey (1961) report on radio-carbon dating of the Tura ropes at 2130±150 years old (ca. 320-20 BCE). This is consistent with the British Museum’s attribution to the Graeco-Roman period.

Ropes of this description were located alongside limestone blocks excavated within the Tura caves (E.J. Hall, personal communication based on ca 1942 on-site observation). Although location of these findings indicates usage for hauling quarried rock, there appears to be no significant evidence as yet that these ropes, or their kin, were used significantly in monument or tomb construction beyond the quarries.

Although dated much later than the Dynasty periods in which pyramid and the majority of tomb construction took place, the Tura ropes may carry forward the rope making methods and use of papyrus developed more than a millennium earlier. Examples are the three-strand papyrus ropes from the Middle Kingdom (2055-1650 BCE) were discovered at Deir el-Bersha, on the middle Nile, as described above.

Materials Used

Although uses of animal hide for plaiting or weaving have been found, by far the most prevalent finds have involved plant-fiber ropes. Lucas and Harris (2012 ed.) report that rope findings from the pre-Dynastic periods involve use of reed. Cords from that period were found to be made of flax, grass, esparto grass (Stipa tenacissima) and halfa grass. Other cordage has been made from tree bast: long vertical inner bark fiber, as in Oetzi’s shoes mentioned above.

Those authors (Lucas and Harris) report also that from the First Dynasty (ca. 3100-2900 BCE), papyrus was used, with an example also from the Third Dynasty. Greiss (1948) identified and photographed a “thick” rope made of papyrus culms from the around the beginning of the First Dynasty (ca. 3100 BCE).

8 Men Splitting Papyrus, Tomb of Puimre, Thebes. New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty (ca. 1473-1458 BCE).Copied by Hugh R. Hopgood, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

A question that occurs to me is whether ancient papyrus harvesting placed rope-making using the culms as only a secondary purpose, the primary purpose possibly being to harvest pithy material within the culms for paper-making? An obvious factor would be papyrus abundance, especially in the lower Nile in early Dynasties, thus offering easy harvesting.

Lucas and Harris (ibid.) also report that a rope possibly made of halfa grass was found from the Sixth Dynasty, and one made of flax was found from the Twelfth Dynasty. Importantly, the authors observe that date palm fiber was by far the most common material used for rope making in ancient Egypt.

9 Three-strand rope of palm fiber exhibited in the Royal Ontario Museum. From Deir-el-Bahri, New Kingdom (1567-1085 BCE). Image in public domain (2011).

Rope Making Methods

Although each fibrous source material has different characteristics of significance in rope making, there are similarities in the way ropes were produced. All ropes designed for sustained use involved twisting collected fibers into a few strands, typically three or four. Fibers (for example fibers stripped from leaves or stalks of date palm, with generally short length) were twisted together into a strand using overlapping so that there were minimal discontinuities at any cross-section of each strand. In building each strand, the fibers were twisted in the same circular direction, say anti-clockwise. Once the (three or four) strands were prepared in this way, they were wound together, under tension, in the opposite circular direction — i.e. clockwise if the individual strands had been twisted anticlockwise. As in today’s rope making methods, when the strands are twisted while in tension, they lock together. Bohr and Olsen (2011) provide a mathematical analysis of optimal strand twisting and note that there is a geometrical limit to the helix structure such that, for each length of rope and strand diameter, the number of turns for optimal locking is roughly the same (irrespective of material used). In practice, rope makers everywhere find through practice the ways to apply tension and arrive at the optimal number of turns.

Especially for thick ropes, more than one artisan was needed to control the weaving and to apply tension. Twisting tools and weights were used. A ca. 2300 BCE depiction of two artisans applying twisting tools in rope making is found at the tomb of Akhethotep and Ptahhotep (as copied by Bohr and Olsen, ibid.).

It’s not clear from the archaeological record which ancestral communities first developed the methods used to make rope, using the methods summarized here. Trial and error, over perhaps many centuries, must surely have been applied. Since the oldest known ropes were found in Egyptian monuments, it is reasonable to assume that Egyptian artisans were at the forefront and that other communities, especially around the Mediterranean, benefitted.

Rope Strength and Durability

Given that discovered ancient Egyptian ropes have experienced various degrees of decay, it is not surprising that strength and durability estimates are unavailable or questionable. One narrative, of limited value due to absence of written documentation (E.J. Hall, personal communication), is that a sample length of the Tura cave papyrus culm rope described above (approximately 8 cm diameter) was taken to a British museum in the mid-to-late 1940’s and tested to tensile failure at 9 imperial tons (equivalent to 9 metric tonnes).

Papyrus (culm) strength was, by deduction given its uses described above, sufficient for the purposes of stone hauling and ship rigging even though other materials such as palm fiber may have exhibited greater breaking strength and perhaps durability.

Ropes made using papyrus culms appear to be relatively stiff and thus may be unsuitable for applications requiring tight bending (for example, around a timber post or a ‘Hassan’ “pulley” as described above). In comparison, modern hemp and manilla ropes are relatively flexible.

Starting with a well-tested modern-day product, hemp, and focusing on a reference rope thickness of 8 cm, a breaking point strength of approximately 30 metric tonnes[2] is specified in a commercial product – thehempshop.co.uk (accessed in August 2025). Hemp ropes are regarded as among the strongest of natural fiber ropes today but hemp ropes are not reported from ancient Egypt.

Imprints of hemp fabric and cordage have been found on pottery in China, dated as far back as ca 4000 BCE (Lu and Clarke, 2012). However, there is no evidence as yet that ancient Egyptian rope makers had access to this fiber.

Value of Rope

In the context of sourcing available material and the manual labor involved in rope making, ropes must have been highly valued and their sustained strength over many months or years of use must have been important. Veldmeijer (2009) relies on other sources in stating that a New Kingdom price for 100 cubits (about 50 m) of rope (of unspecified material and diameter) was equivalent to two head of cattle. Clearly, ropes were valuable.

Aesthetic and Spiritual Context

Rope making and uses are shown in numerous paintings and reliefs in royal tombs, such as that of Khaemweset, son of Ramesses II (Teeter, 1987). The majority of these tombs are of the Old Kingdom. Teeter observed that scenes of cord-making were usually placed adjacent to scenes of boat building or adjacent to agricultural activity, presumably indicating uses of the cordage.

More symbolically, one of many hieroglyphs is known as a “shen ring,” depicted as a stylized loop of a rope bound to a stick, typically completely encircling the name of a pharaoh or sometimes a god/goddess, thus eternally protecting that personage (Lightbody 2021).

Since even the Shen ring hieroglyph as a protective cartouche demonstrates the high value of rope and cordage in Ancient Egypt since predynastic times before the Bronze Age and throughout, this brief survey of rope and cordage in Ancient Egypt summarizes that long history of valuing binding material, even when organic and normally subject to decomposition, except here in an arid environment when ephemeral material can survive millennia in the desert in closed tombs or caves.

Notes:

Barker, M. and J. Mackay. “British Museum Natural Radiocarbon Measurements III. Item BM-79, Tura Caves.” Radiocarbon, 3 (1961), pp 39-45.

Bohr, J. and K. Olsen. The ancient art of laying rope. EPL 63, 60004 (2011). https://epljournal.edpsciences.org/articles/epl/abs/2011/06/epl13372/epl13372.html

Borojevic, R. and R. Mountain. “The Ropes of Pharaohs: The Source of Cordage from ‘Rope Cave’ at Mersa/Wadi Gawasis Revisited.” Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 47. (2013) 131-41.

Fleckinger, Angelika. Ötzi the Iceman. Bolzano: Folio Books, 2011, esp. 67-8.

Greiss, E.A.M. Anatomical Identification of plant fibers from ancient Egypt (with three plates). Bulletin de I’Institut d’Egypte, 31 (1948), pp 249-278.

Hall, E.J. served as an officer in the South Africa Engineers Corps in World War II and was stationed for a brief period in Cairo, Egypt, ca 1942. Associated with British forces making use of the Tura caves, he observed the papyrus ropes. Personal communication with the author occurred on several occasions over the period 1960-1970.

Hardy, B., M. Moncel, C. Daujeard, P. Fernandez, P. Béarez, E. Desclaux, M. Navarro, S. Praud and R. Galotti. “Impossible Neanderthals? Making string, throwing projectiles and catching small game during Marine Isotope Stage 4 (Abri du Maras, France).” Quaternary Science Reviews 82 (2013) 23-40. Elsevier.com.

Hassan, S. The Great Pyramid of Khufu and its Mortuary Chapel. Excavations at Giza, Season 1938-39, Vol X.Cairo General Organization for General Printing Offices (1960).

Lightbody, David Ian. “New Symbols of Hierarchy: On the Origins of the Cartouche and Encircling Symbolism in Egyptian Pyramids.” The Ancient Neat East Today 9.7 (2021).

Lu, X. and R. Clarke. “The cultivation and use of hemp (Cannabis sativa) in ancient China.” http://internationalhempassociation.org/jiha/iha02111.html

Lucas, A. and J.R. Harris. Ancient Egyptian Materials and Industries, E. Arnold, London, 4th ed. (1962).

Mark, S. The Earliest Sailboats in Egypt and Their Influence on the Development of Trade, Seafaring in the Red Sea, and State Development. Journal and Ancient Egyptian Interconnections. http://jaei.library.arizona.edu. Vol 5.1 (2013), pp 28-37.

Moores, Bob. Building the Pyramids. How did they do it? Universe (2019).

Pulak, C. The Uluburun Shipwreck and Late Bronze Age Trade. In Beyond Babylon: Art, Trade, and Diplomacy in the Second Millennium B.C. J. Aruz, K. Benzel, and J.M. Evans (eds.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art Exhibition Catalog (2008), pp. 288-305, artifact catalog: 306-310, 313-321, 324-333, 336-342, 345-348, 350-358, 366-378, 382-385. Also found at https://cgs.la.psu.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/27/2020/12/Pulak-2008-Reading.pdf.

Schottenhammer, A. “The ‘China Seas’ in world history: A general outline of the role of Chinese and East Asian maritime space from its origins to c. 1800. Journal of Marine and Island Cultures 1 (2012) 63-86. www.sciencedirect.com.

Teeter, E. Techniques and Terminology for Rope Making in Ancient Egypt. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 73.1, (1987) 71-77.

University of Southampton. “Black Sea expedition discovers world’s oldest intact shipwreck.’ Contact listed: Professor Jon Adams (2018). https://www.southampton.ac.uk/news/2018/10/oldest-intact-shipwreck-found.page

Veldmeijer, A. Cordage Production, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 1.1,( 2009).

Wachsmann, Shelley. “On the interpretation of watercraft in ancient art.’ Arts 8.165 MDPI (2019) 1-67.

Ward, C. Building pharaoh’s ships: Cedar, incense and sailing the Great Green. British Museum Studies in Ancient Egypt and Sudan, 18 (2012).

[1] Earlier versions of this publication date back to Harris (no coauthor) in 1945.

[2] Adjusted for listed diameters offered by the vendor and converted to metric tonnes.