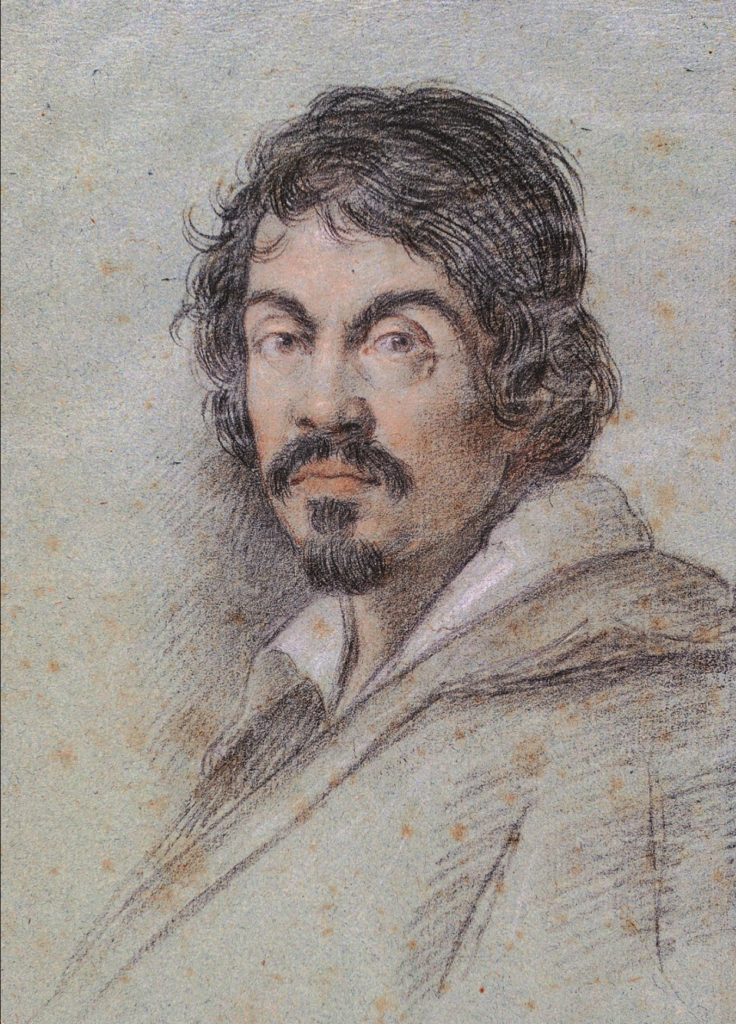

Ottavio Leoni, Caravaggio portrait sketch early 17th century,. Biblioteca Marucelliana, Firenze

By Leslie Ilic –

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, known universally as Caravaggio, was a genius Baroque painter. Much of his life, and certainly his death, is shrouded in mystery, due to the lack of contemporaneous accounts of his activities. But from what can be pieced together, it may be that lead poisoning was very likely a key factor in his mercurial nature – he may not have died outright from lead poisoning, but he likely lived with it longterm. Temperamentally, Caravaggio’s quickness to anger, violent outbursts, and his increasing use of tenebrism as his career progressed might be partly attributed to his heavy lead exposure.

When a skeleton was located in Porto Ercole in 2010 – claimed by Silvano Vinceti, the forensic scientist who exhumed it – to be Caravaggio’s bones and consonant with his age of 39 at death, these bones were found to be riddled with lead. “Caravaggio’s suspected bones come complete with levels of lead high enough to have driven the painter mad and helped finish him off. ‘The lead likely came from his paints – he was known to be extremely messy with them,’ said Vinceti, the forensic researcher who announced the findings” . [1] When lead is ingested, especially consistently over years, it creates a reservoir in the bones. When a body has lead in its bones, it means lead can be released consistently in the blood stream, even if a person has occasional relief from direct lead exposure. As Caravaggio aged, and the “frequency of severity of [his] legal scapes were increasing” ,[2] it went far beyond “the temporary self-poisoning of artists from the grinding and mixing of painting concoctions”.[3] Even though Caravaggio may not have been painting constantly, the lead accumulating within his body was ensuring consistent toxicity. As will be discussed below, as Caravaggio aged, his temperament became more volatile, his threshold for violence lower, and his paintings darker. There are some disagreements about the quality and certainty of Silvano Vinceti’s work, sensational at times, [4] but after DNA links to other members of Caravaggio’s family by Vinceti, a team from the Marseille Université used dental pulp from the remains to further establish the identity as Caravaggio, and further investigate his exact cause of death as connected to being weakened by an intense staphylococcus infection,[5] so for the purposes of this discussion, the bones with high lead level can be fairly reliably considered to be those of Caravaggio.

Male Skeletal bones, about 39 years old at death, high in lead content, from Porto Ercole 2010: Caravaggio’s? (courtesy of Silvano Vinceti)

Caravaggio apprenticed to another painter at thirteen years old, which meant his exposure to lead started early. “Apprentices would have been expected to grind colors from natural sources for painting pigments, and the young Caravaggio must have spent hours preparing canvases and laboriously working at grinding and mixing powdered materials” .[6] Add to this that Caravaggio had no studio with apprentices himself – possibly only one in his lifeline – and thus had to grind his pwn pigments throughout his artistic career. While some materials used for paint were relatively harmless, many like lead white and orpiment and realgar – the latter with mercury sulfide – were quite toxic. Particularly those minerals ground for yellow and white, which were lead based (the mercury sulfide basis of cinnabar red is also highly toxic, but the discussion of its contributing effects are not the primary concern of this paper). “The greatest exposure to lead were most likely the painters, because of the use of lead-based colors, including lead carbonate (or cerussite, also known as “white lead”), lead carbonate 2PbCO3·Pb(OH)2 as a substance which was irreplaceable with the realization of the color “white” until the nineteenth century”.[7]

Powdered white lead carbonate pigment – 2PbCO3·Pb(OH)2 (image public domain)

When pigments are ground for use in paint, they are pulverized into incredibly fine powders, which made inhalation unavoidable. Caravaggio would have been surrounded by lead in the air around him, in addition to directly on his skin as he worked as a teenager, day in and day out. Lead exposure as he went through puberty would have been especially toxic. “[In children] lead probably is taken up at calcium absorption sites, which have increased activity at times of rapid growth” . Caravaggio’s lead exposure was worse as a young person than it would have been if he had been exposed later, and the constancy of exposure would have led to absorption in his bones. [8]

This early exposure also may have laid the foundation for his reputed hot temper later in life. “[Childhood] Chronic exposure to lead affects numerous neurotransmitter systems, increasing the spontaneous release of dopamine, acetylcholine, and gamma-amino butyric acid…these effects result in an increase of random synaptic signals..and decrease in the ability of the neuron to produce a synaptic signal in response to a true stimulus”.[9] Misfiring synapses create a wide variety of problems in the human brain: random bouts of euphoria or anger, lowered ability to experience fear or restraint, and behavioral abnormalities. Disrupted signals across the brain prevent the correct flow of information, can alter how people experience cause and effect, and can lead to strong emotions without provocation. It is clear from descriptions of Caravaggio’s nature that he went beyond ‘hot headed’ – lead might have played a part in how his brain developed, and his youthful exposure may have deprived him a sense of fear in dangerous situations, and any ability for self control in times of anger.

The continued exposure to lead as Caravaggio became an adult could have accentuated his problems. “In adults, workers with occupational exposure to Pb have shown to have…increased interpersonal conflict” . [10] Caravaggio’s lawlessness increased as he aged, his interactions with law enforcement are well documented. Caravaggio’s reckless disregard for rules and quick temper was likely exacerbated by the style in which he painted, because it involved the direct ingestion of lead. He was famous for incredibly fine details, often in lead-derived white paint, which meant he was licking his brushes, to get as fine a point as possible (a common technique). In ‘Boy bitten by a Lizard’, “Although the picture seems to have been painted for the most part in walnut oil, a sample taken from a white highlight of the shirt sleeve near the elbow shows this passage to have been painted in a mixture of oil and egg tempera, a medium which produced a cooler and more opaque white than would have been obtainable with oil alone” .[11]

The egg tempera would have been much more palatable, especially since lead is known to be sweet, which meant he could ingest quantities of white paint when working on details without filling his mouth with bitterness. Lead was not known to be toxic at the time, and Caravaggio continued to grind his own pigments, meaning he was continually increasing his exposure to lead and poisoning therefrom throughout his life. After inhaling pigments and ingesting paint, his disposition towards ‘increased interpersonal conflict’ was clear. “Caravaggio possessed a nature that was not easily subdued. His frequent fighting and sword-blustering suggested a bad temper and a short fuse, mixed with a fiery pride” .[12] A precise delineation between which facets of his personality were innate, and which were caused by lead are impossible to determine – but when considering how much lead he could have ingested, over how many years, it is very clear there the lead made an impact.

Caravaggio had a history of violence, which became more pronounced as he aged. The exact amount of lead Caravaggio was exposed to (and quite probably consumed) is difficult to precisely pinpoint, but the effects of even a relatively low amount of lead are well documented. “Scientists have yet to place a threshold to identify the level below which lead exposure does not result in an intelligence quotient loss…neuro-imaging techniques appear to support the existence of organic damage and the emergence of different types of behavioral disorders…all-cause mortality, renal impairment, cardiovascular disease, infertility, and neurological disorders” . [13] Caravaggio did not employ apprentices, probably partially due to his erratic behaviors and general instability, making it difficult to work with him, which meant he was grinding his own pigments throughout his life. Any neurological issues caused by lead may also have contributed to his problems with his patrons, leading to his financial turmoil. Caravaggio clearly experienced disordered behavior, and the uncertain cause of his death, thought to be some kind of fever, possibly from an untreated raging staph infection, could also have been made worse by the quantity of lead in his system. “Lead exposure may also decrease lifespan…the mortality of 4292 subjects with blood lead levels of 20-29 µg/dl was compared to those with levels of <10 µg/dl. Subjects with higher lead levels has a 46% increased all-cause mortality, 39% increased cardiovascular mortality, and 68% increased cancer mortality”. [14] Chronic lead exposure may have changed Caravaggio’s behavior, and likely shortened his life. All the lead exposure was cumulative – grinding the pigments for paint and inhaling them in the air; his messy painting habit ensuring absorption of lead through the skin, and finally licking his brushes to a fine point to create his famous precise details in white lead carbonate paint.

Beyond his physical and mental health, lead may have also affected Caravaggio’s style of painting. One of the key effects of lead poisoning is reduced contrast sensitivity in a persons’ vision, which may be the root of Caravaggio’s use of tenebrism. “The drama of light and shade, the total dense gloom in his pictures was a particularly emphatic expression of the new axiology which treated shadow and darkness as a value” .[15] Tenebrism was one of Caravaggio’s most defining artistic signatures, spotlighting figures with sharp illumination for heightened emotional intensity. Caravaggio’s dramatic lighting was consistent with his naturalistic aims, but could have also been influenced by an impairment of his vision. Caravaggio’s paintings increased in contrast, and in violent imagery, as he grew older. “Later, driven by his peculiar temperament, he gave himself up to the dark style, and to the expression of his turbulent and contentious nature”. [16] In the ‘Penitent Magdalene’, Caravaggio’s abundant white highlights around her shirt and pearls, as well as the virtuosity of perfection of the glass perfume alabastron against the dark background, perfectly exemplify the tenebristic contrastive techniques he was developing. But even in this exquisite painting he could resist provoking the Catholic Church by using a sex worker as a model. It is impossible to quantify how much lead he would have consumed when working on the details, presumably using a single-haired brush, especially on the white lacing of her bodice and her bracelets, using his saliva to keep the brush hair to a fine point. Note the white highlights in Caravaggio’s ‘Taking of Christ’ (1602) and ‘Beheading of John the Baptist’ in Valetta Cathedral, Malta (both below). Lead was seemingly a key factor in Caravaggio’s masterpieces, both as a tool and likely as an ultimate impairment.

Caravaggio, The Taking of Christ, 1602, National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin (image public domain)

There has been informed speculation that Caravaggio was impacted by the lead content of his paints, [17] which was seemingly confirmed when the bones were identified in 2010 as having high lead content. Caravaggio was first exposed to lead as an apprentice, more detrimental because he was going through puberty, and continued to be exposed once he became a professional painter. It is not possible to calculate the exact extent of his lead poisoning, but from what was written about his temperament, and what we now know about lead poisoning and its effects, it is clear there is a correlation. Caravaggio’s irritable, irascible personality became more pronounced as he aged, as did the darkness and ferocity of his paintings, as many of his paintings in Malta and Sicily show from around 1608, paintings so dark extra light is required to view them, e.g., ‘Burial of St. Lucy’, ‘Nativity with Shepherds’, and ‘Raising of Lazarus’.

Caravaggio, Beheading of John the Baptist (1608) Oratory of Cathedral of Valetta (image public domain)

Caravaggio was unquestionably a revolutionary artist, but equally plausible, he may have suffered terribly from constant exposure to toxic lead when he painted. His overall health also undermined, he may have perished more quickly than a healthy person on the coast at Porto Ercole in 1610, as forensic analysis of the skeleton – both high in lead and bacterial staphylococcus traces – said to be Caravaggio’s bones make apparent. Even if somewhat speculative in this Porto Ercole skeleton’s case, exposure to lead for an artist who ground his own pigments would show just such devastating effects for a long-compromised immune system.

Notes:

[1] Tom Kington, “The Mystery of Caravaggio’s Death Solved at Last – Painting Killed Him,” The Guardian, June 16, 2010, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2010/jun/16/caravaggio-italy-remains-ravenna-art.

[2] Patrick Hunt, Caravaggio (London: Haus Publishing Ltd, 2012), 99-100.

[3] ibid. Hunt, 100

[4] Elisabetta Povoledo, “Unearthing Doubts About Caravaggio’s Remains,” The New York Times, July 4,2010, https://www.nytimes.com/2010/07/05/world/europe/05italy.html.

[5] Michel Drancourt et al., “Did Caravaggio Die of Staphylococcus Aureus Sepsis?,” The Lancet Infectious Diseases 18, no. 11 (November 2018): 1178, https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(18)30571-1.

[6] Hunt, 7

[7] Michele Augusto Riva et al., “Lead Poisoning: Historical Aspects of a Paradigmatic ‘Occupational and Environmental Disease,’” Safety and Health at Work 3, no. 1 (March 30, 2012): 11–16, https://doi.org/10.5491/shaw.2012.3.1.11, 12.

[8] Danyal Ibrahim et al., “Heavy Metal Poisoning: Clinical Presentations and Pathophysiology,” Clinics inLaboratory Medicine 26, no. 1 (March 28, 2006): 67–97, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cll.2006.02.003, 87.

[9] ibid., Ibrahim, 87.

10] Pan Chen, Mahfuzur Rahman Miah, and Michael Aschner, “Metals and Neurodegeneration,” F1000Research 5 (March 17, 2016) 366, https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.7431.1.

[11] Larry Keith, “Three Paintings by Caravaggio,” National Gallery Technical Bulletin 19 (1998):37–51, 39.

[12] Hunt, 53-54

[13] Riva, 15. 13

[14] Herbert Needleman, “Lead Poisoning,” Annual Review of Medicine 55, no. 1 (February 1, 2004): 209–22, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.med.55.091902.103653, 217.

[15] Maria Rzepinska and Krystyna Malcharek, “Tenebrism in Baroque Painting and Its Ideological Background,” Artibus et Historiae 7, no. 13 (1986): 91–112, https://doi.org/10.2307/1483250, 106.

[16] Keith Christiansen, “Caravaggio and ‘L’esempio Davanti Del Naturale,’” The Art Bulletin 68, no. 3 (September 1986): 421–45, https://doi.org/10.2307/3050975, 453.

[17] Hunt, 100

References

Chen, Pan, Mahfuzur Rahman Miah, and Michael Aschner. “Metals and Neurodegeneration.”F1000Research 5 (March 17, 2016): 366. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.7431.1.

Christiansen, Keith. “Caravaggio and ‘L’esempio Davanti Del Naturale.’” The Art Bulletin 68, no. 3 (September 1986): 421–45. https://doi.org/10.2307/3050975.

Drancourt, Michel, Rémi Barbieri, Elisabetta Cilli, Giorgio Gruppioni, Alda Bazaj, Giuseppe

Cornaglia, and Didier Raoult. “Did Caravaggio Die of Staphylococcus Aureus Sepsis?”

The Lancet Infectious Diseases 18, no. 11 (November 2018): 1178. https://doi.org/

10.1016/s1473-3099(18)30571-1.

Hunt, Patrick. Caravaggio. London: Haus Publishing Ltd, 2004.

Ibrahim, Danyal, Blake Froberg, Andrea Wolf, and Daniel E. Rusyniak. “Heavy Metal Poisoning: Clinical Presentations and Pathophysiology.” Clinics in Laboratory Medicine 26, no. 1 (March 28, 2006): 67–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cll.2006.02.003.

Keith, Larry. “Three Paintings by Caravaggio.” National Gallery Technical Bulletin 19 (1998) 37–51.

Kington, Tom. “The Mystery of Caravaggio’s Death Solved at Last – Painting Killed Him.” The Guardian, June 16, 2010. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2010/jun/16/caravaggio-italy-remains-ravenna-art.

Needleman, Herbert. “Lead Poisoning.” Annual Review of Medicine 55, no. 1 (February 1, 2004): 209–22. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.med.55.091902.103653.

Povoledo, Elisabetta. “Unearthing Doubts About Caravaggio’s Remains.” The New York Times, July 4, 2010. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/07/05/world/europe/05italy.html.

Riva, Michele Augusto, Alessandra Lafranconi, Marco Italo D’orso, and Giancarlo Cesana. “Lead Poisoning: Historical Aspects of a Paradigmatic ‘Occupational and Environmental Disease.’” Safety and Health at Work 3, no. 1 (March 30, 2012): 11–16. https://doi.org/10.5491/shaw.2012.3.1.11.

Rzepinska, Maria, and Krystyna Malcharek. “Tenebrism in Baroque Painting and Its IdeologicalBackground.” Artibus et Historiae 7, no. 13 (1986): 91–112. https://doi.org/10.2307/1483250.