Trafalgar Silver Vase, ca. 1806, estate of Lord Cottesloe (Image courtesy of Fitzwilliam Museum Cambridge)

By Timothy J. Demy –

Artistic trends and movements do not arise in a vacuum; they are birthed and shaped by the intellectual ideas, religious and cultural values, and current events of the era in which they emerge. Viewing an object in a museum or online is seeing the piece removed from its original environment and all that the environment entailed. But to have a greater understanding and appreciation of what is being viewed there should be awareness and knowledge of the society and culture in which it was created and used. Things beyond size, shape, decoration, and construction must be considered. Those are important but not sufficient for full understanding of what one is viewing. Understanding the origins and importance of an object are the first steps in moving beyond the level of being satisfied with the aesthetic appeal only of a piece or a collection toward a deeper connoisseurship. Questions and considerations cause us to slow down our movement through a museum gallery. When we do so, we are able to think, consider, and make connections are often missed.

The Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, England is always worth a visit. Founded in 1816, the museum is the lead partner of remarkable collections of the University of Cambridge Museums (UCM) and the Botanic Garden. More than half a million works of art and historical artifacts are held by the museum in its world-renowned collection. The museum’s size makes it a comfortable but not overwhelming experience as might be the case in some museums.

Fitzwilliam Museum Cambridge (image public domain)

A Fitzwilliam exhibition in the recent past (2023) titled “Refugee Silver: Huguenots in Britain” highlighted items from the museum’s collection that were crafted by Huguenot silversmiths from 1680 to the 1720s. Fleeing religious and political persecution in France following the 1685 Revocation of the Edict of Nantes (also known as the Edict of Fontainebleau) by Louis XIV, more than 50,000 Huguenots (French Protestants, mostly Calvinists) fled to Britain. Others sought refuge in the Netherlands, Switzerland, Italy, Germany, South Africa, and North America. This exodus came a little more than a hundred years after the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre of August 24 to October 3, 1572; during which up to 70,000 Huguenots were killed. The massacre was one event during a series of civil wars between Roman Catholics and Protestants in France in the late 16th century. In seeking “refuge” in Britain and elsewhere, these persecuted French citizens introduced into the English vocabulary a new term that remains well-known in the present day—“refugee.”

Silver gilt tea caddy, marked London, Aymé Videau, 1746–46, Fitzwilliam Museum, given by estate of the late Oliver and Peter Ward (courtesy of Fitzwilliam Museum)

Huguenot refugees came to Britain seeking safety, freedom, and the opportunity to practice their professions and trades—among them, silversmithing. Some came as much for economic as religious reasons. Louis XIV had ordered the melting of silver to pay for war expenses and the building of the palace at Versailles and this had direct economic consequences for many people. In their new homes in Britain, Huguenot silversmiths made a significant contribution to the cultural life of Britain. Silversmiths were not the only craftspeople to enter British life and culture—there were also those whose trade and skills were in carving, woodworking (boiserie), textiles, printing, and sculpting. Yet it is the polished work of the silversmiths that most visibly adorned the tables and other furniture in rooms of British homes. Their pieces blended distinctive Huguenot and French patterns with contemporary British style, retaining elements of the old country and blending them with elements of the new country. In so doing, they created a distinctive style and legacy. Among the more famous of the Huguenot silversmiths who came or whose family came to Britain were Paul de Lamerie (1688–1751), Pierre Platel (c. 1664–1719), and Lewis Mettayer (active 1700–d. 1740).

Silver Cup, Paul de Lamerie ca. 1717, Gilbert Collection Victoria & Albert Museum (image courtesy of V&A)

As precious metals, silver and gold have always had an exalted place among the decorative arts such that these metal artifacts were in a different aesthetic category from those of wood, porcelain, and glass. The high monetary value of gold and silver, as well as the ability to melt, recast, and redesign the objects created from them provided economic and artistic benefits in volatile times and with changing trends and fashions.

Formerly living primarily in French provincial cities, Huguenots were a strong presence in the merchant class. In addition to silversmiths, they were prominent in papermaking, silk and woolen weaving, stocking and glove-making, and the export trade.

When one looks at Huguenot silver, there is precision, style, sophistication and even flamboyance in the designs. They are intricate and visually appealing. One can find themes from Greek and Roman history and mythology as well as from the 17th and 18th centuries (and earlier). Although they retained distinctive elements of their own French culture and heritage, they also adapted them to British tastes and styles–especially those of the emerging wealthy British middle class. They understood the desire for luxury items and the styles that decorated them. In so doing, these Huguenot silversmiths created a new British style that became dominant in their new homeland and one that had a lasting effect on arts and crafts in Britain.

In the 18th century, consumer demand for new and luxury items rather than the stricter artist–patron relationship of previous centuries created a shift in those who purchased the work of silversmiths, now based largely in London. There were still aristocratic patrons, but the emerging middle class also dramatically expanded the consumer base for silversmiths. Now, the purchaser might or might not have a relationship with the silversmith as a regular patron. The popularity of new and fashionable drinks such as coffee, tea, and chocolate also created a demand for smaller pieces of silver than those used in formal dining.

The ascension of George I in 1714 and a coinciding period of peace between Britain and France from 1714–1744 allowed a wave of French arts and designs to enter Britain without political suspicions of the British consumer. This too enhanced the market for silversmiths. During the prime years of Huguenot silversmiths (1680–1760), the finished pieces were rarely the work of a single artist even though the “maker’s mark” stamped on the piece was that of one person, generally the head of the atelier as master silversmith. There was usually a long chain of other embedded workers crafting the piece before the silversmith whose mark appeared on the piece—designers, modelers, raisers, chasers, casters, engravers, and planishers.

By the late 1600s and early 1700s, engraving became much more elaborate. Heraldic engraving especially showed a change from heraldry engraved for identification and functional purposes to detailed aesthetic engravings. The trend continued well into the 19th century with pieces being created to commemorate battles and other historic events.

One example of this is the “Trafalgar Vase” The vase was one of 73 vases ordered by the Patriotic Fund which was a group of businessmen who were concerned with rewarding bravery during the Napoleonic Wars of 1803–1815. Ten vases was presented to ship captains involved in the Battle of Trafalgar (1805). The vase in the present image was presented to Vice Admiral Sir Thomas Francis Fremantle (1765–1818), Captain of HMS Neptune. It was designed by John Shaw and John Flaxman and made by Digby Scott and Benjamin Smith II for Rundell, Bridge, and Rundell, London. Note the Classical relief of one of the earliest Labors of Heracles, in this case the slaying of the Hydra of Lerna.

The Trafalgar Vase, ca. 1806, on loan for exhibition by the Estate of Lord Cottesloe (Photo by author)

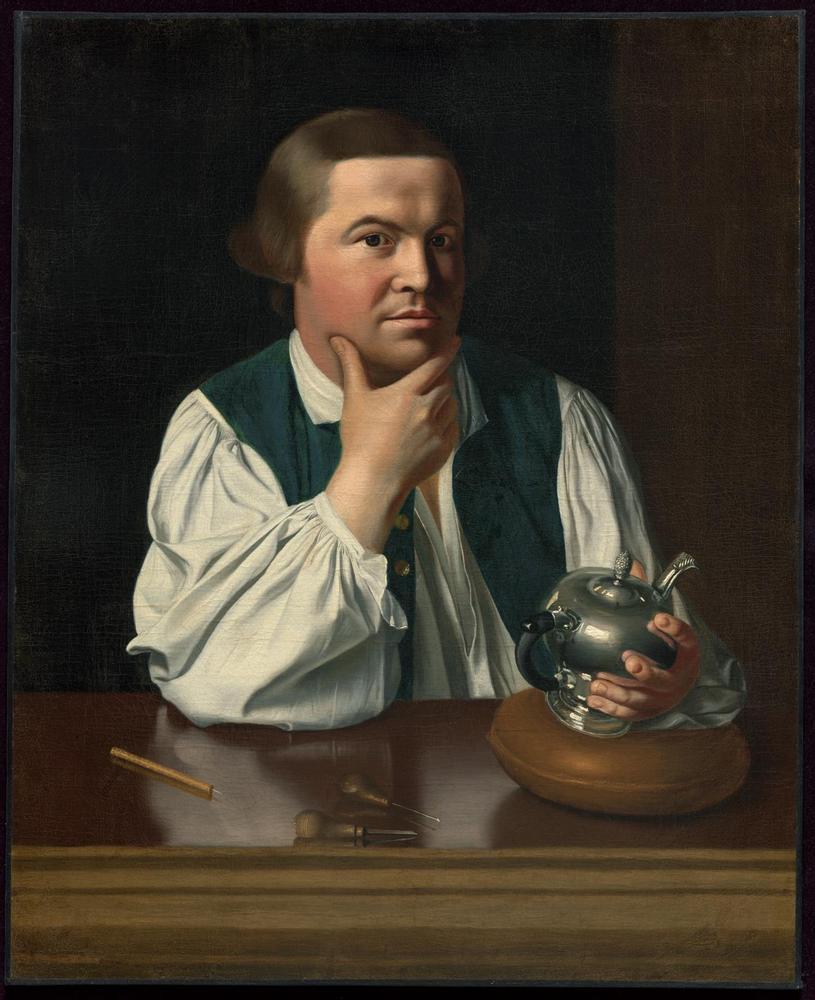

Not to be overlooked is the transatlantic flight of Huguenot refugees to the British colonies in America. Among those who came to North America was a goldsmith named Apollos Rivoire, who was born in 1702, in Riocaud, in the Gironde valley, near Bordeaux. Once in the American colonies, Rivoire (d. 1754) changed his name to Revere. He was the father of American patriot and silversmith Paul Revere. Other prominent silversmiths of Huguenot heritage (though not necessarily direct French émigrés) in America included Bartholomew Le Roux (1663–1713), Cesar Ghiselin (ca. 1672–1713), Rene Grignon (ca. 1672–1715), Simeon Soumain (1685–c. 1715), and Thauvet Besley (ca. 1691–1757).

Paul Revere, 1768 painting by John Singleton Copley, oil on canvas. Gift of Joseph W. Revere, Wm. B. Revere and Edward. H. R. Revere. Boston Museum of Fine Arts (Image public domain)

Although it is too generous to say that Huguenot silversmiths created the aesthetic trends of English silver in the 18th century, they certainly met the needs of the social élite in Britain as they looked to France for trends in style, whether it be in cuisine, architecture, fashion, art, or items of silver. French influence had been present in the second half of 1600s, especially in London, but the skilled Huguenots arrived at a time and in numbers to capitalize (literally) on growing consumer demands. In so doing, they left a remarkable and beautiful legacy.

Further Reading

Cottret, Bernard. The Huguenots in England: Immigration and Settlement, c. 1550–1700. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Gwynn, Robin D. Huguenot Heritage: The History and Heritage of the Huguenots in Britain. Eastbourne, UK: Sussex Academic Press, 2001.

Hartop, Christopher. The Huguenot Legacy: English Silver 1680–1760. London: Thomas Heneage, 1996.

Hayward, J. F. Huguenot Silver in England 1688–1727. London” Faber & Faber, 1959.

Ormsbee, Thomas Hamilton. “The Huguenot Silversmiths, 18th Century Refugees,” American Collector, July 1939 at https://www.collectorsweekly.com/articles/the-huguenot-silversmiths-18th-century-refugees/

**************

Timothy J. Demy is a professor at the U.S. Naval War College (Newport, RI) and retired Navy chaplain. He is a graduate of the University of Cambridge with a master’s degree in international relations. Elsewhere, he earned doctorates in historical theology and also in the combined fields of technology and the humanities. The author and editor of numerous books and articles, he is an avid bibliophile, classical music lover, and student of piano.