Cover image of Tony Hall book D-Day: Operation Overlord, 1993, Smithmark Books (Image in public domain)

By Timothy J. Demy –

I walked the beach alone. It was an early Sunday morning and for several hundred yards on either side of me there was no one. No sound, except for the gentle ripples of water edging slowly toward the dry sand. The only footprints were mine and they were quickly erased in the wet sand with the incoming waves. It was peaceful and quiet. One might think it had always been that way. Not so. As I knelt down to feel the wet sand and have it sift through my fingers it was hard to imagine what had happened there decades earlier. It was Omaha Beach, Normandy, the site of Operation Overlord, the largest amphibious invasion in history.

There are many memorable images of the D-Day beaches on June 6, 1944. Surely the most graphic were carried in the memories of the young soldiers, friend and foe, who fought there. The majority of those remained private, viewed, if at all, only descriptively in the company of other veterans or visually in the terrors of the night.

But there were and are other photographs, taken in the midst of the greatest amphibious battle and invasion known in human history and left to future generations—left to us. When we view them we do so in the quietness of a library, in the safety of our homes, in the marbled rooms of museums, in noisy classrooms, and on the calm of a computer screen.

As we gaze and consider each image that passes before us, we can do so with the click of the electronic mouse. How different those environments are from the one in which the photographs were taken and from the experiences of those who took the photographs. It wasn’t calm; it wasn’t quiet; and they certainly couldn’t hear the click of the camera shutter.

There are many quotes about photographs. Two common ones, each with its own unique history are: “A photograph is the pause button of life” and “A picture is worth a thousand words.” Both are certainly true of D-Day photographs—and some of the photographs were much more than pause buttons. To be sure, if a photograph is worth a thousand words, then there are some photographs that are worth a thousand looks—to pause, to look (and look again), to reflect, and to remember.

Photographs of D-Day are numerous—and every one of them tells a story that is worth at least a thousand words. To view them is to visually wade into a world or enter another world—a world of sacrifice, service, and adrenaline. It is a world of combat, chaos, and confusion. It is a world of terror and trauma and unimaginable levels of noise.

The best-known photograph of American troops on D-Day (Photo 1 below) is probably National Archives image 26-G-2343, an official U.S Coast Guard photograph taken by Chief Photographers Mate Robert F. Sargent. It shows U.S. Army troops of Company E, 16th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division—the “Big Red One”—wading ashore on Omaha Beach. It was taken from the back of a U.S. Coast Guard LCVP, the abbreviation for Landing Craft Vehicle, Personnel but known more commonly as a “Higgins boat,” named after its designer Andrew Jackson Higgins of New Orleans. Jackson originally manufactured shallow-water work boats to support oil and gas exploration in the Louisiana bayous.

The photograph of the landing craft with its ramp down and American soldiers headed to Omaha Beach is a one-frame visual summary of the event. Many would not make it ashore. The LCVP in the famous photograph was from the USS Samuel Chase (APA-26) that was manned by a Coast Guard crew. By the time the Samuel Chase and its LCVP neared the beaches of Normandy, the ship had already served in Operation Torch (North Africa, 1942), Operation Husky (Sicily, 1943), Operation Avalanche (Gulf of Salerno, 1943). After D-Day (Operation Neptune), it would serve in Operation Dragoon (Southern France, 1944), and then move to the Pacific Theater of Operations, participating in the Battle of Okinawa (1945).

Photo 1: “Into the Jaws of Death 23-0455M” Higgins Boat from USS Samuel Chase, Robt. Sargent, photographer (Image Public Domain)

During the initial landing imaged in the iconic photo, two-thirds of Company E became casualties. Only friends and loved ones would see it.

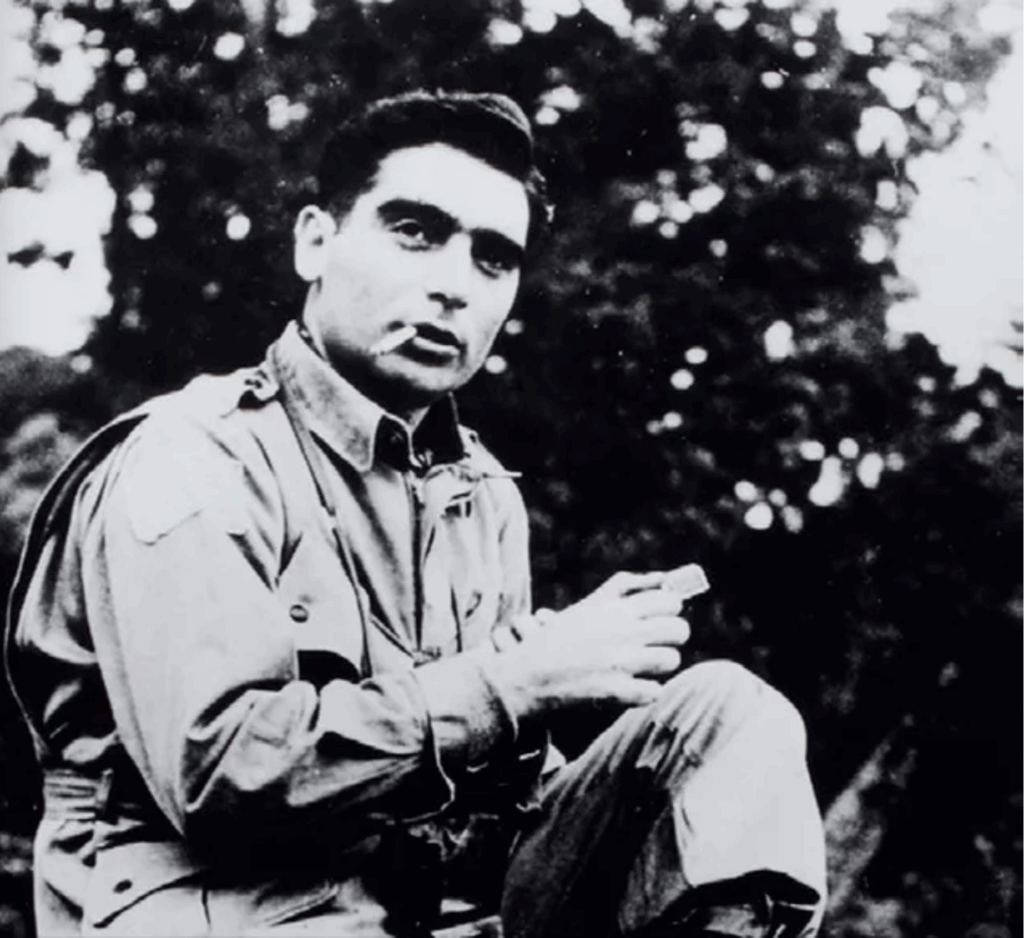

The photograph that remains with me is one that was taken by combat photographer Robert Capa (1913–1954). Photographing the war, Capa (Photo 2 below) understood the traumas and tragedies of it and any conflict. He would say at one point, “I hope to stay unemployed as a war photographer till the end of my life.”

Photo 2: Robert Capa, 1913–1954. (Photo courtesy of Robert Capa Contemporary Photography Center, Budapest, Hungary)

By the time Capa took his photographs on D-Day in the waters of the beaches of Normandy, combat photography was almost a hundred years old. The first war images known are from a series of fifty daguerreotype slides taken in 1847 in Saltillo, Mexico by an unknown American photographer during the Mexican-American War (1846–1848). For British and European viewers, the Crimean War (1853–1856) was the conflict that provided them with images of conflict. The American Civil War (1861–1865) produced some of the best-known early photographs of war through the efforts of photographers such as Mathew Brady, Alexander Gardner, and Timothy H. O’Sullvan..

That was all history. On June 6, 1944, D-Day wasn’t yet history—it was the present. For many young men, it was also their last day.

The D-Day image I can’t forget (Photo 3 below) is that of an American GI in the surf struggling to crawl ashore on Omaha Beach. Blurred and low resolution, it is one of Capa’s few surviving (and controversial) D-Day photos known collectively at “The Magnificent Eleven.” Less than two weeks after the photographs were taken, they were published in the June 19, 1944 issue LIFE magazine under the heading “Beachheads of Normandy: The Fateful Battle for Europe is Joined by Sea and Air.” (A detailed photograph of the GI in the water was published 10 years later in the June 7, 1954 issue of Life, p. 29).

Photo 3 (Omaha Beach Photo by Robert Capa © International Center of Photography)

Omaha Beach—there is a contested history of this Capa images, but no one contests that he was the photographer. The photo was likely taken about 0830 on the Easy Red Sector of Omaha Beach during the 13th wave of Americans of the 16th Infantry Regiment going ashore.

Now more than 80 years later, all but a few of the young men of D-Day (Allied and Axis) are gone. What does it mean now to gaze upon the images? Is it voyeuristic? Is it self-indulgent? Perhaps a bit. But even more so, it is to reflect and to remember—it is a responsibility.

Robert Capa said of photographs and photographers, “If your pictures aren’t good enough, you aren’t close enough.” He was close enough.

So were others—too close.

My best friend’s father was a survivor of Omaha Beach on June 6, 1944. He rarely spoke of his experiences, though he did do so with me a couple of times. Perhaps it was because he had known me most of my life and because I was a Navy chaplain. After the death of my father, I called him every year on Christmas Day, on Father’s Day, and on D-Day.

On the D-Day of our last call, he was in his 90s. Friendly, and outgoing as I had always known him to be to me, we talked briefly of D-Day. He told me “It was a long time ago, but you can’t forget.” I responded that it was because of that memory that I was calling once again as an American to say “thank you.” He said nothing for probably 30 seconds; he then responded firmly but quietly, saying simply: “We did the best we could.”

Such words and the images we have from that historic day are well worth our pausing to look and remember.

Further Reading

Balkoski, Joseph. Omaha Beach: D-Day, June 6, 1944. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2006, rep. ed.

Capa, Robert. Slightly out of Focus. New York: Modern Library, 1999.

Herrick, Charles R. Back into Focus: The Real Story of Robert Capa’s D-Day. Havertown, PA: Casemate Publishers, 2024.

McManus, John C. The Dead and Those About to Die, D-Day: The Big Red One at Omaha Beach. New York: Penguin Publishing, 2015.

Walton, Stephen. The D-Day Landings: IWM Photography Collection. London: Imperial War Museum, 2024.

Note: the National Archives R. Sargent photo 1 is copyrighted via WikiMedia Commons Potd/2012-06-06 (en)]

Timothy J. Demy is a professor at the U.S. Naval War College (Newport, RI) and retired Navy chaplain. He is a graduate of the University of Cambridge with a master’s degree in international relations. Elsewhere, he earned doctorates in historical theology and also in the combined fields of technology and the humanities. The author and editor of numerous books and articles, he is an avid bibliophile, classical music lover, and student of piano.