By Patrick Hunt –

Introduction

Significant prior studies have summarized and at times specifically delineated the ways Vermeer employed music in his carefully-wrought and subtly staged mise-en-scène genre paintings. One of the most recent and fairly comprehensive is Marjorie Wieseman’s excellent Vermeer and Music: The Art of Love and Leisure, 2013, National Gallery, London, where Wieseman has curated Dutch and Flemish art and where her companion volume covered the concurrent 2013 exhibition by the same name. Additional prior studies include those of Cone, Harmon, Melo, Buijsen, and the extremely useful and detailed online corpus of Adelaide Rech in Essential Vermeer, among others.[1] This brief essay places Vermeer in context with other Dutch musical genre paintings and then selectively examines a few salient details of several Vermeer paintings with musical subjects, specifically The Music Lesson of 1663 and The Guitar Player ca. 1672.

Overview and Dutch Musical Contexts

As an overview before examining two selected Vermeer works, although a dozen out of 35 confirmed Vermeer paintings depict musical moments or allude to music in some form, the Wieseman National Gallery catalog only features five peerless Vermeer music paintings: The Music Lesson of 1663 (as catalog entry 21 pages 62-3, A Young Woman Standing at a Virginal ca. 1671, A Young Woman Seated at a Virginal ca. 1671, The Guitar Player ca. 1672 (as catalog entry 24 pages 68-9), and the other Young Woman Seated at a Virginal ca. 1670-72, but does not address details of The Concert ca. 1664, or Girl Interrupted at Her Music of 1660, or others where there are musical instruments only peripheral to the scene as in The Glass of Wine ca. 1658-61. This London exhibition catalog also covers many other contemporary artists of the 17th century, noted in the following discussion in more detail. Another Vermeer exhibition catalog from the Louvre in 2017, Vermeer et Les Maitres de la Peinture de Genre edited by Blaise Ducos, also covers some of the same artists and genre scenes. [2] I was fortunate to view both of these exhibitors, first in London in 2013 and following in Paris in 2017. This brief essay owes much to these exhibitions and their curators and authors as well as to Rech in The Essential Vermeer 3.0 and another resource, Art Facts.[3]

It is vital to place Vermeer in context – he certainly did not exist in a musical vacuum – with other contemporary artists in the Dutch Golden Age (ca. 1588-1672 or roughly most of the 17th century), [4] since music is a frequent subject or art least present in the burgeoning art of this time and place when the Dutch culture flourished in nearly every way including global reach partly brought about through the Dutch East Indies Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie or VOC) from 1602 onward.

For comparanda, almost a third of Vermeer’s output deals with music in some form or represents musical instruments for whatever reason, including themes of love and perhaps the healing power of music. Likewise in the genre paintings of other artists, as Buijsen and Rech note:

“…that Vermeer portrayed so many musical themes is not surprising in itself, ‘in at least ten percent of all seventeenth-century paintings, music makes its appearance in one way or another. In genre pieces, in which category Vermeer’s work is generally placed, the percentage is even higher. For example, about 20 per cent of Frans van Mieris’ works, 25 per cent of Pieter de Hoogh’s and almost half of Jacob Ochtervelt’s deal in some way with music.’ ”[5]

Wieseman’s 2013 exhibition catalog shows many of these similar paintings by Dutch artists including Jan Steen, Joost Cornelisz, Gonzalez Coques, Roelandt Savery, Louis Finson, Jan Miense Molenaur, Jacob van Campen, Frans Pourbus the Elder, Gerard ter Borch, Hendrick ter Brugghen, Gerrit Dou, Carel Fabritius, Pieter de Hooch, Thomas de Kayser, Gabriel Metsu, Frans van Mieris the Elder, Jacob Ochtervelt, Jan Olis, Godfried Schalcken, Harmen Steenwyck, Jan Jansz. Treck and Jacob van Velsen.[6] Similarly, in addition to Vermeer works the 2017 Louvre exhibition showcased either many of these same paintings or artists (not necessarily musically themed) including de Hooch, Metsu, ter Borch, van Mieris, Dou and Ochtervelt, but also other contemporary Dutch or German painters such as Caspar Netscher and Eglon van den Neer. [7] In these two exhibition catalogs from the last decade, the musical Dutch genre paintings most similar to Vermeer’s are by ter Borch, Dou, Metsu, van Mieris, Steen, Schalcken, and Ochtervelt, who in some cases may have set the precedent that Vermeer followed since he knew other artists and their work as both a collector/dealer and artist. According to Gower: “There is evidence that Vermeer paid close and critical attention to the pictures that passed through the art market in Holland.”[8]

In addition to vocal subjects, instruments depicted in these paintings include keyboards such as virginal (especially muselar), clavicimbel or clavichord, lute, cittern, guitar, flute, violin, viola da gamba, recorder (blockflute) for serious – often private – concerts as well as hurdy-gurdy, bagpipe, tambourine, drum, and rommelpot for other kinds of musical entertainment in tavern scenes or similar public events.[9] Whether to accompany contemplation and philosophy or love and seduction or merely frivolity and bacchanalia, the use of music is altogether compelling and seemingly ubiquitous in Dutch life in Vermeer’s time.

Select Vermeer Musical Moments

Selectively examining two of Vermeer’s most characteristic musical subjects, The Music Lesson (1663) and The Guitar Player (ca. 1672) respectively, emphasizes Vermeer’s famous attention to detail regarding music and instruments.

First, with the long perspective view of Vermeer’s The Music Lesson (1663, Royal Collection Trust UK, 73.3 x 64.5 cm) the background details in a black and white marbled floor-tiled room demand attention, especially the keyboard and the viol da gamba at rest in the middle ground. Virginals of the 17th century are usually small, often portable, keyboards of the harpsichord family, often the keyboard instrument of choice of young ladies in the Baroque Era, which may explain the instrument name as well, although another etymology suggests derivation from the Latin virga for the jack housing the plectrum of each key. This Vermeer keyboard is clearly a virginal of the muselar type where the the actual keyboard is on the righthand side of the string housing box which is also angled sideways or perpendicular to the player for space-saving reasons; muselar cases often also rest on tabletops as most have no legs. A virginal has one wire string per key which plucks the wire, resulting in a slight delayed action. The plectra are mounted in jacks on the invisible side of the keyboard case. Pushing down on the keys results in a light metallic timbre producing gentle or soft sounds which often cannot be heard on the other side of closed door, so a virginal was often intended as a fairly private instrument.

One of the most fascinating details in Vermeer’s Music Lesson is the almost certain identification of a famous keyboard workshop, the Andreas Ruckers shop in Antwerp, as the maker of the instrument Vermeer paints, complete with its decorative Arabesque paper design above the actual keys and on the inside top cover, the Latin phrase MUSICA LETITIAE CO[MES] MEDICINA DOLOR[IS], which translates “Music, companion of joy, balm of sorrow.” I might add that a variant reading could be “medicine for pain”. A near identical virginal has survived from the Andreas Ruckers workshop in Antwerp from ca. 1579-1652 as seen in the Koninklijk Oudheidkundig Genootschap (KOG or Royal Antiquarian Society Museum) in Amsterdam and at times on loan to the Riksmuseum in Amsterdam, its size also comparable to Vermeer’s depiction at 1.50 meters long, and .5 meter high, as noted in Wieseman (see image below within this text). Its Latin aphorism on its inside cover is very similar to Vermeer’s, reading MUSICA LABORUM DULCE LEVAMEN, translating to “Music, the sweet consolation of work.” Neither of these Latin quotations are unique to these two instruments. [10]

Additionally as mentioned, in Vermeer’s middle ground is a Baroque viol da gamba (also known as a a viol or “leg viol”, from Italian gamba “leg”) played between the legs, with the bow held “underhand” as opposed to a cello bow position. The shape of a viol da gamba tapers gradually “shoulders sloping to the neck” as opposed to a more rounded violin cello body “meeting…at right angles” to the neck.[11]

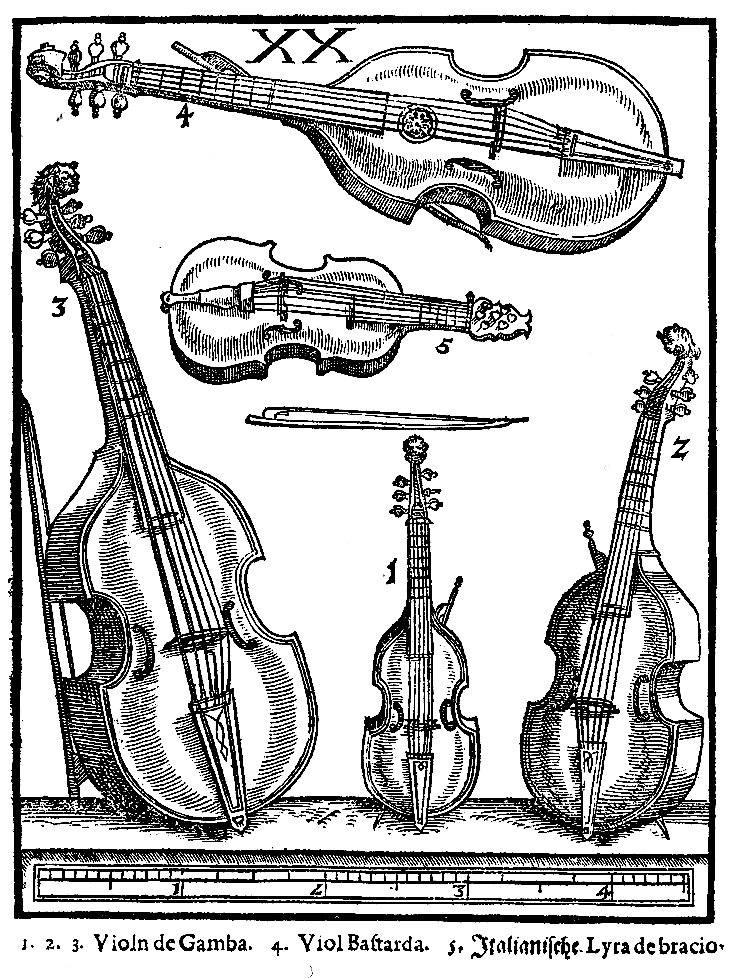

This viol is at rest in the Vermeer painting, laid down between the table, blue leather chair and the standing girl. Vermeer’s is a fairly similar image of contemporary instruments in collections such as a Baroque viol made of maple and spruce, ca. 1640-65, at the Metropolitan Museum, New York, 1 meter 15 cm length [12] (see image below in this text); or similar to another in the Royal College of Music Collection in London, made by Barak Norman between 1670-1740, maple and conifer at 1 meter 20 cm length. [13] The added viol family image (below) is from Michael Praetorius’ Syntagma musica ca. 1615.

Second, the equally famous Vermeer painting we know as The Guitar Player (ca. 1672, Iveagh Trust at Kenwood House, London, 53 x 46 cm) with its unusually offset young musician depicts one of the most joyful faces of a young woman in any art known to us, here playing her small guitar, in fact, the only depiction of a guitar in Vermeer. As Rech observes, Vermeer has deliberately blurred the strings to possibly imply they are vibrating, “painting movement rather than substance”, a “tour-de-force“ and done in an “unconventional manner which finds few parallels in seventeenth century painting.”[14] Plus, as Rech quotes Wheelock in the same passage:

“…the bright and direct character of The Guitar Player spoke more to the modern world of music represented by the guitar than to the conservative and contemplative traditions of the lute.” [15]

That her joy is directed toward or derives from someone outside the plane of the painting adds mystery but does not in any way detract from the magnitude of her emotion. Other details have been often analyzed: one can establish the haute bourgeoisie wealthy social position of the young woman including the gilded-frame painting behind her, a typical Vermeer painting-within-a-painting identified as a landscape of Pieter Jansz van Asch, A Wooded Landscape with a Gentleman and Dogs (ca. 1670) or a similar earlier landscape now in Grenoble by Herman van Swanevelt (1644) at Musée des Beaux-Arts de Grenoble, helping to ante quem date this Vermeer. The same yellow starched satin morning coat trimmed with faux ermine has been depicted in five other Vermeers, and the expensive pearl necklace both imply her wealth and status, as also the three books on the background suggest her education. [16]

As musicologists have debated,[17] the guitar itself may be the historical descendant of the ancient Greek kithara both etymologically (kithara to cittern to guitarra to guitar: initial k/g velar stop + medial t apicoalveolar stop /or dental fricative [θ, č] + terminal r coronal) and structurally as plucked or strummed strings over a sounding box, which in most ancient kitharai was a tortoise shell. The notes produced by these strings plucked or strummed could be adjusted as frequencies with harmonics along the length of the string as Pythagoras noted millennia ago. The Greek kithara was the instrument of choice for bards, singers and poets. In the 6th c. BCE, Sappho, who was arguably the greatest Greek lyrical poet, composed many love songs for the kithara and even invented a new type of plectrum, and is forever associated with love poetry and epithalamia (wedding songs, some of them no doubt plangent as an ancient Greek wedding could also be a bittersweet ending of maidenly life).

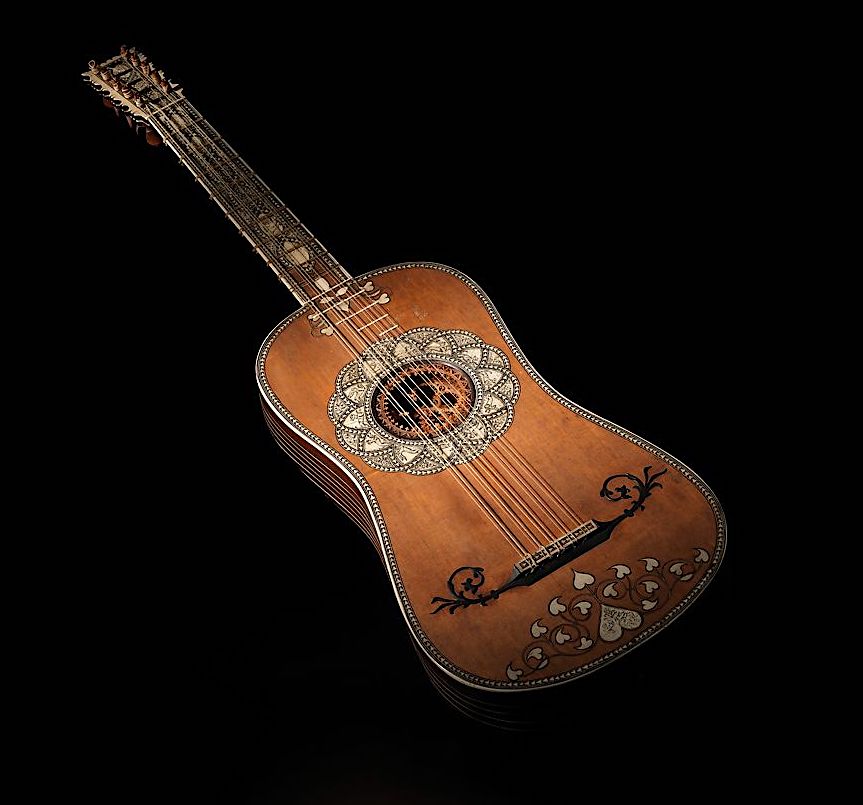

Vermeer’s knowledge about the guitar is shown, including in this case a Spanish vihuela guitar – a five course gut string instrument often tuned very much like a lute, complete with its bigote (mustache) bridge figure [18] and ivory and ebony purfling around its face and neck. The Baroque or Spanish guitar – a fairly novel instrument in 17th c. Netherlands – was often an accompaniment especially to the expression of love, which interpretation appears to be more than just a possibility in this painting. Intriguingly, vihuela is a Spanish term that essentially means “viola” as related to the viol family (viola de mà in Catalan), also represented by the viola da gamba, except this guitar of Vermeer is small and held, thus usually not played with a bow (although there is also a vihuela de arco) but strummed or plucked. Vermeer’s guitar has a gilded sound hole that shows his virtuoso mastery of light, here coming from the right, which is also unusual for him. For comparanda, note a Metropolitan Museum New York example from the collection as well as Wieseman’s image (see text image below).[19]

Observations that the music being played in the Vermeer painting is related to love are reinforced if the chord she seems to be playing with her fingers on the frets – depending on lute or guitar tuning, ambiguous here because it could be tuned either like a lute or like a guitar – can be identified as the key of E Minor, one of the most basic chords on a guitar which any guitar player will immediately recognize by the fingered fret position, suggesting Vermeer intended this observation or at least this ambiguity to the viewer as E Minor is a chord so often associated with love in all its vicissitudes of desire and longing as well as heartache and separation. But here regardless of the chord (although it is a profound philosophic antithesis if she is playing a minor key), it is joy recorded by Vermeer while she is playing the guitar (thinking about her lover?), a joy perhaps inspired by the sudden appearance of the very one so loved and missed up to this point. Modern philosophic interpretations of Vermeer sometimes imply his at least incipient knowledge or assimilation of Plato’s Ideals but this may be a stretch, however profound his art and our intellectual contemplative reactions to his mastery of painting, although we can visually understand how we can connect an intellectual thread from Plato onward in appreciation of the sublime in artistic achievement.[20]

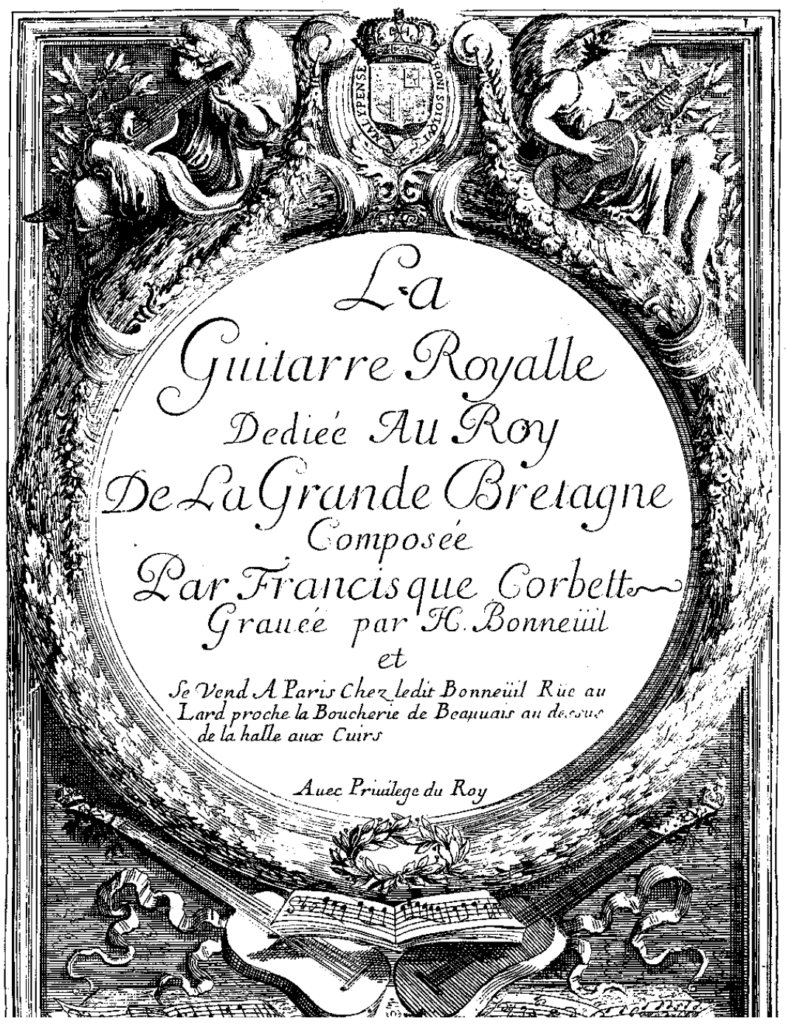

Regarding what kind of possible guitar music may be played in The Guitar Player, although this is conjectural because there is no way to know, one of the popular composers of the time who wrote music for the Spanish vihuela guitar was Francesco Corbetta (1615-81) whose many pieces include dance suite solos such as his “Almand (Allemand) in E minor”, his “Preludium in E Minor” and his “Corrente (Courant) in E Minor” – all of them with both plucking and strumming – and whose music was certainly present in the Netherlands.[21]

Yet Vermeer does not tell us the conclusion or the exact context, only the moment of seeing her while not seeing the object of her gaze. This is a synesthesic or eidetic (multisensory) moment because Vermeer has also given us a trope for sight as we see (visual) her looking (visual again) outside the scene while she touches (tactile) the strings that produce sounds (auditory) we can only imagine.[22] A rich eidetic sensory experience likely so connected to love’s awakening of the senses as the amatory call of Song of Songs 4:12 and 4:16 demands [23] may be mostly indirect, but the guitar player’s delight is anything but indirect even if we cannot see the object of her sight. Such is the genius of Vermeer.

Conclusion

Thus, while Vermeer’s musical subjects are certainly not isolated depictions comparing other Baroque Dutch music genre paintings of the 17th century, on the other hand his painterly command of detail is stunningly accurate in its fidelity to musical instruments of his day. Any philosophic intent of Vermeer is not addressed here other than to the allusion of the power of music faithfully recorded on the inside virginal cover of a likely Ruckers of Antwerp keyboard in The Music Lesson: “Music, companion of joy, medicine of sorrow,” which Vermeer does not contradict but subtly reinforces. Likewise, the joy on the face of The Guitar Player seems to verify this power, either as a synesthesic prelude to love or allusion to its awakening of the senses (here visual, auditory and tactile) or as an equally-powerful emotive solace. Whether or not Vermeer experienced these musical benefits personally or was a musician himself is immaterial to the genius of his rich visual art so carefully and uniquely rendered.

Notes:

[1] Edward T. Cone, “Music: A View from Delft” The Musical Quarterly XLVII.4 (1961) 439-53; Edwin Buijsen, “Music in the Age of Vermeer” in Donald Haks and Marie Christine van der Sman, eds., Dutch Society in the Age of Vermeer, The Hague and Zwolle: Hague Historical Museum & Waansers Uitgevers, 1996, esp. pp. 106-23; Roger Harmon, “ ‘Musica laetitia comes’ and Vermeer’s Music Lesson” Oud Holland 113.3 (1999) 161-6; James Melo, “Review: From Boisterous Noise to Inner Silence: The Depiction of Musical Instruments in Vermeer’s Paintings” Music in Art 26.1/2 (2001) 147-50; Adelheid Rech, “Music in the Time of Vermeer” Essential Vermeer 2005 (http://www.essentialvermeer.com/music/music_start.html).

[2] Marjorie E. Wieseman. Vermeer and Music: The Art of Love and Leisure. London: National Gallery of Art, 2013, distributed by Yale University Press; Blaise Ducos. Vermeer et les Maitres de la Peinture de Genre. L’album de l’Exposition. Paris: Louvre Museum / Somogy, Editions d’Art, 2017. This author (Hunt) viewed both of these exhibitions.

[3] Vermeer, Art Facts: A Quest for Beauty and Knowledge, curated by Trace Bradley and other artists (https://art-facts.com/facts-about-johannes-vermeer/) and their related links online.

[4] Simon Schama. The Embarrassment of Riches: An Interpretation of Dutch Culture in the Golden Age. New York: Knopf, 1987; Helmer J. Helmers and Geert Janssen, eds. The Cambridge Companion to the Dutch Golden Age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018, esp. 268-88; Norbert Wolf. The Golden Age of Dutch and Flemish Painting. London & Munich: Prestel, 2019.

[5] A. Rech, 2005, quoting Buijsen, 106 (see note 1).

[6] Wieseman, pp. 13-16, 24,-25, 26-27, 29, 34-61; figs. 3-6, 15-20; Catalog paintings 1-20.

[7] Blaise Ducos, pp. 2, 6-21, 23-35, 37-39, 41-45, 47.

[8] Lawrence Gowing. “Johannes Vermeer” Paintings in the Louvre. New York: Stewart, Tabori and Chang (Workman Publishing Group), 1987, 452; also Walter Liedtke, “Vermeer Teaching Himself” ch. 2, in Wayne Franits, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Vermeer, Cambridge University Press, 2001

[9] Wieseman, 18-21; 73-76

[10] Wieseman, 21. Note this same Latin maxim MUSICA DULCE LABORUM LEVAMEN is also written below the double keyboard virginal on a Metropolitan Museum in that collection made by Hans Rucker the Elder (1545-98), made in 1581, in Antwerp, Gallery 684, Accession #29.90 (https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/503676).

[11] Percy Scholes, “Viol Family”, Oxford Concise Dictionary of Music, 2nd ed. 1964, 1977 printing, 603-04. See image in text from Michael Praetorius Syntagma musicum of 1615-19, fig. XX (also in Scholes, 604).

[12] Musical Collection, Gallery 681, Division Viol, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, R. A. Lehman Bequest, Accession # 2009.42; also see Herbert Heyde. “Recent Acquisitions, A Selection: 2008-2010.” Fall 2010. Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 68.2 (2010), illustration; also see Elizabeth Weinfeld, “Delicate Quiet Beauty: the Viola da Gamba” in MetMuseumOrg., June 25, 2014 (https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/of-note/2014/viola-da-gamba) regarding this same Met Museum instrument.

[13] Wieseman, 19

[14] See Jayson Kerr Dobney and Wendy Powers, “The Guitar.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/guit/hd_guit.htm (September 2007); also note A. Rech, “Musical Instruments in Vermeer’s Paintings: The Guitar” Essential Vermeer 3.0 (http://www.essentialvermeer.com/music/guitar.html).

[15] Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., Vermeer and the Art of Painting, New York and New Haven: Yale University Press. 1995, 149–150 (quoted in Rech in n13).

[16] The guitar player’s wealthy social position was noted by Elise Goodman “The Landscape on the Wall in Vermeer” ch. 5 in Wayne Franits, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Vermeer, Cambridge University Press, 2001; according to some the Jansz painting was identified by Gregor Weber, others like Bert Meijer suggest a wooded landscape by Herman van Swanevelt; the books symbolize education as Walter Liedtke suggests. Much of this is summarized in Essential Vermeer 3.0 (http://www.essentialvermeer.com/catalogue/guitar_player.html#.XMd1-i-ZMUs).

[17] Emanuel Winternitz. “The Survival of the Kithara and the Evolution of the English Cittern”, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 24.3/4 (1961) 222-29; Carla Zecher, “Ronsard’s Guitar: A Sixteenth-Century Heir to the Horatian Lyre”. International Journal of the Classical Tradition 4.4 (1998) 532-54.

[18] Ian Woodfield, The Early History of the Viol, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1984, 6, 38-60, 92; Jonathan le Cocq, “Reviewed Work: Performance on Lute, Guitar and Vihuela: Historical Practice and Modern Interpretation by Victor Anand Coelho”, Music and Letters 80.1 (1999) 105-08; Bernadette Nelson, “Adventures and Enchantments: New interpretations of Spanish Music” Early Music 35.1 (2007) 141-44.

[19] Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Guitar Collection, ca. 1630-50, five course Spanish guitar attributed to Matteo Sellas (1599-1654), active in Füsssen, Germany and Venice, Italy, Gallery 684, spruce, bone, parchment, ivory, Accession # 1990.103; Wieseman, 20

[20] e.g., Robert D. Huerta. Vermeer and Plato: Painting the Ideal. Bucknell University Press, 2005

[21] cf. selected Corbetta guitar pieces performed Jakob Lindberg, Baroque Guitar, 1997, on PrestoMusic BIS CD-799 Digital (https://www.prestomusic.com/classical/products/7937362–corbetta-guitar-music#tracklist) including the Preludium, Almand and Corrente. Note Rech’s mention of Corbetta’s Varii scherzi di sonate per la chitara spagnola published in Brussels 1648 (http://www.essentialvermeer.com/music/guitar.html).

[22] Patrick Hunt, “Sensory Images in the Song of Songs.” Beitrage zur Erforschung des Alten Testaments und des Antiken Judentums, Band 28 (188-94). Peter Lang Verlag, Frankfurt, 1996, 147-54, including Sappho and Samuel Taylor Coleridge eidetikos; Patrick Hunt, “Subtle Paronomasia in Canticum Canticorum.” Beitrage zur Erforschung des Alten Testaments und des Antiken Judentums, Band 20 (147-54). Peter Lang Verlag, Frankfurt, 1992, 69-78.

[23] note Martha Hollander, “The Cambridge Companion to Vermeer”, Historians of Netherlandish Art Reviews, Nov. 2002 (https://hnanews.org/hnar/reviews/cambridge-companion-vermeer/) regarding Elise Goodman “The Landscape on the Wall in Vermeer”, ch. 5 in Wayne Franits, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Vermeer, Cambridge University Press, 2001, although what some call a “Petrarchan conceit of a woman in a garden” antedates the Italian poet by at least two and a half millennia, as the medieval “enclosed garden” or cloister garden recalls Song of Songs 4:12 “A garden locked (גַּן נָעוּל) is my sister, my bride, a garden locked a fountain sealed,” and 4:16 “Awake (ע֤וּרִי), O north wind, and come, O south wind! Blow upon my garden that its fragrances may be wafted abroad.” (New Revised Standard Version tr., M. Coogan, ed., New Oxford Annotated Bible, 3rd ed., 1991 printing, 964). Also cf. Patrick Hunt, “Sensory Images in theSong of Songs.” IOSOT Congress (International Organization for the Study of the Old Testament) Paris, College de France, University of Paris-Sorbonne, 1992 (abstracts). For other Near Eastern allusions to the enclosed garden paradise motif, also see Patrick Hunt, “Persian Paradise Gardens: Eden and Beyond as Chahar Bagh.” Electrum Magazine July 2011 (https://www.electrummagazine.com/2011/07/paradise-gardens-of-persia-eden-and-beyond-as-chahar-bagh/).