By Jess Taylor –

In late summer 2007 we decided to drive due south from Istanbul to Antalya. On day three, driving deep into central Turkey from Iznik – the modern name for ancient Nicaea but later famous for its Iznik ware porcelain in the Ottoman period – we detoured southwest just after Kuthaya about 60 kilometers for an afternoon visitor the ancient town of Aizanoi and its unique temple of Zeus. Aizanoi in Western Turkey was in the region of Phrygia – originally a Hittite domain a millennium earlier – and adjacent to the Penkalas River.

Crossing over a still-functioning Roman stone bridge above the Penkalas River, one capable of bearing modern traffic, the famous temple loomed in sight above us as a rarity of archaeological preservation as we were stopped temporarily by a military checkpoint. Being so far off the beaten path, I’m not sure who was more surprised to find each other, them, or us, but after some lengthy questioning we were left alone to visit the ruins. Immediately afterwards a villager bounded from his home situated across the street and approached us. Speaking no English yet clearly proud of the heritage, he handed us a guidebook to the ancient city and invited us onto the grounds (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Cover of gifted guidebook published in 1998 by the director of the Museum Kütahya, Metin Turktuzun. Photo by Jess Taylor.

Ancient Aizanoi

Aizanoi (Αἰζανοί in ancient Greek, Aezani in Latin) is dubbed the “Second Ephesus” and in 2012 Aizanoi joined the Tentative Lists of UNESCO World Heritage.

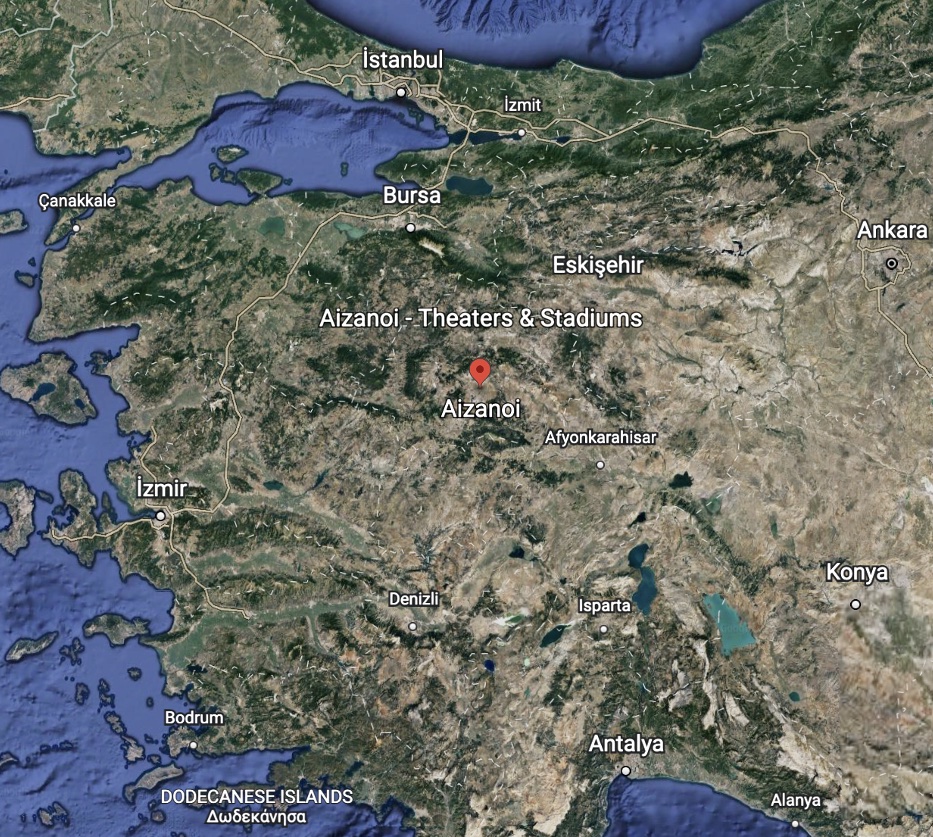

Aizanoi was originally a city of the western Anatolian Phrygian empire. It is located within current day Çavdarhisar, near Kütahya. The ruins are set in the high plains near the Penkalas River (now Kisiboğaz Creek) at an elevation of approximately 1000 meters (3,300 ft) (Figure 2).

The name Aizanoi is possibly derived from the mythical hero named Azan, one of the three sons of the legendary king Arkas, and the nymph Erato. Azan is traditionally considered the forefather of the Phrygians who settled along the river near the cave of the local goddess Meter Steunene.

Aizanoi came under Roman control in 133 BCE and experienced its golden age during the second and third centuries CE.

An ancient settlement, evidence for occupation dates to the 3rd millennium BCE. In Hellenistic times the entire region alternated between the hegemonies of Pergamon and Bithynia.

Now very much set in quiet countryside, Aizanoi became an important political and economic center during Roman times. It was known for its production of grains, wine, and sheep’s wool and economic trade.

Most of the current ruins date from the Roman Imperial period. They are quite extensive consisting of the Temple of Zeus, five Roman bridges (two of which are still in use), an agora, two bath complexes, a unique stadium / theater complex, a trading building, cemetery, tombs, protective dams, quarries, and the sacred cave of Meter Steunene, spread across approximately 35 square kilometers. The relative position of the most important ruins is shown in Figure 3 (approximately 6 square kilometers).

Figure 3: Detail of the major Aizanoi Roman ruins showing the area with the greatest concentration, approximately 6 square kilometers. Photo captured from Google Earth and annotated by Jess Taylor.

Aizanoi began minting coins during the 2nd and 1st centuries BCE and continued through the Imperial period. Figure 4 displays an example of a coin with the head of Hadrian (left, obverse), a true Philhellene emperor and patron of Aizanoi (described later), and a customary depiction of Zeus of Aizanoi (right, reverse).

Figure 4: Silver tetradrachm 128-138 CE with Hadrian depicted on the left (obverse) and Zeus of Aizanoi on the right (reverse). Photo from forumancientcoins.com.

Becoming inconsequential after the 7th century CE, the ruins were rediscovered by European travelers in 1824. The grounds were surveyed between 1830 and 1840. The first excavations began in 1926 and remain active today. In fact, just announced in 2021, a tremendous Roman coin hoard was recently discovered at Aizanoi consisting of over 650 Roman coins.

Figure 5 & lead image: Temple of Zeus, Aizanoi, looking from north. Photo by Jess Taylor.

The construction of the temple began in the second quarter of the second century CE. The Philhellene Emperor Hadrian arbitrated an agreement that created the funding for the undertaking. The communications between Hadrian and the Aizanoi were so important that they were displayed in a separate inscription zone on the north side of the entryway (pronaos) of the temple (the opposite side of the temple as shown in Figure 5).

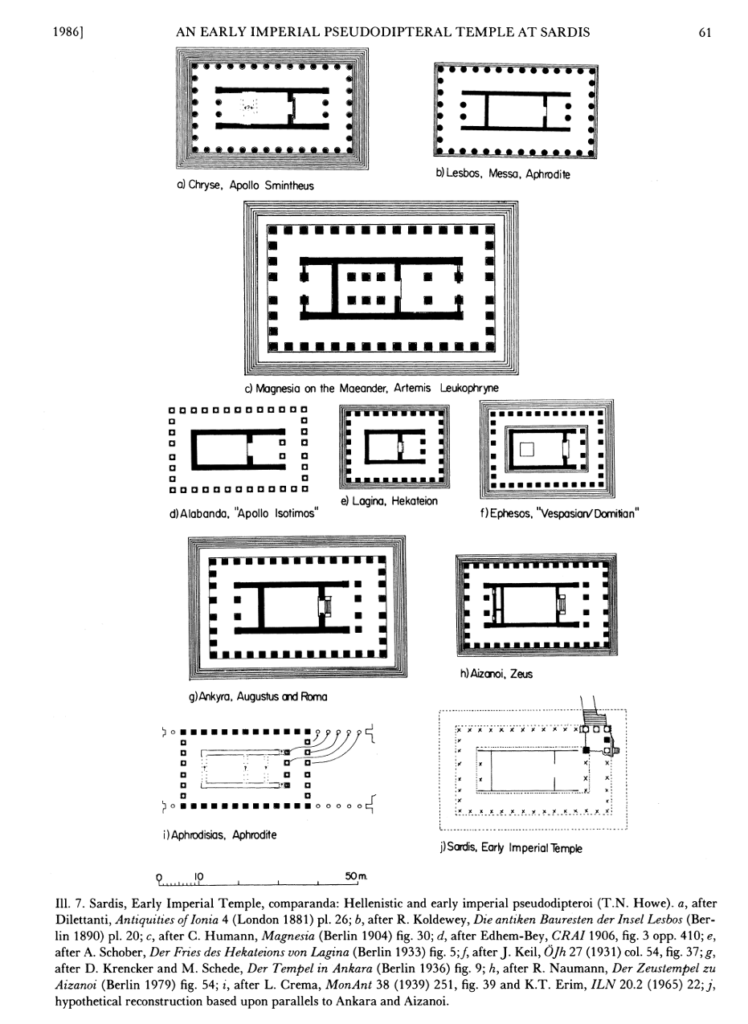

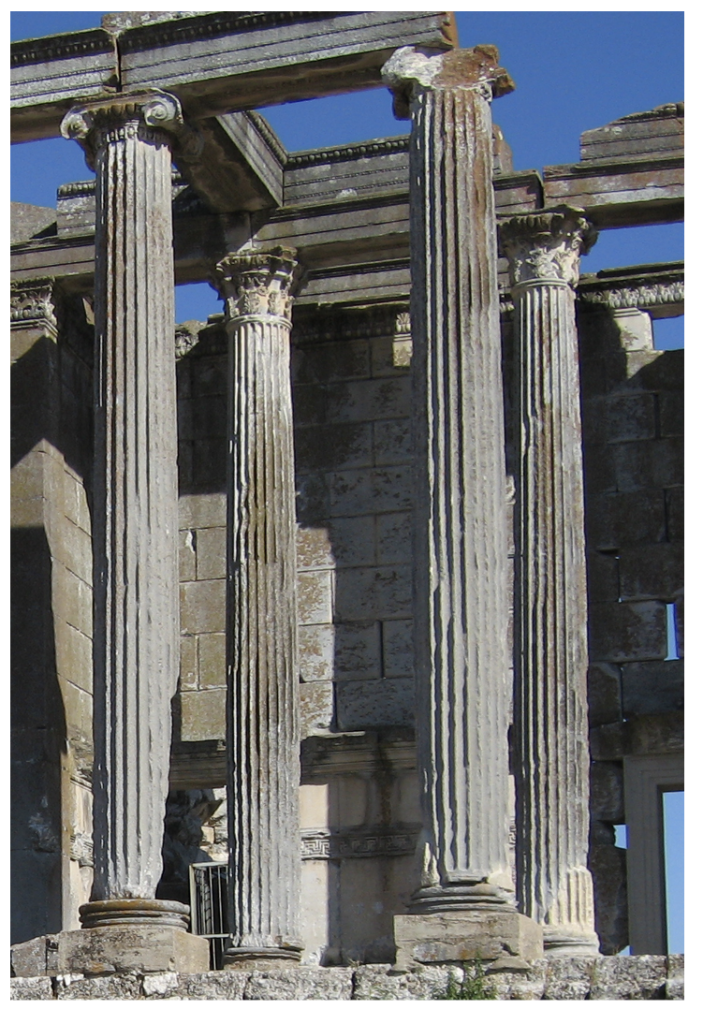

The colonnade (peristalsis) of the temple had eight Ionic columns across the ends and fifteen along the sides (35 x 53 meters). The distance between the columns and the walls of the inner rooms is twice as much as the distance between the columns making the building a pseudodipteros.

The pseudodipteros style is considered a tradition of Roman design during the first century and a half CE. At least eleven pseudodipteros style temples are known to exist in late Hellenistic and early Roman Asia Minor. Figure 6 depicts a subset of these, including Aizanoi.

Figure 6: Depictions of ten pseudodipteroi temples located in Asia Minor. Reproduced from the American Journal of Archaeology (C. Ratte, AJA 1986, Reference #8), with permission.

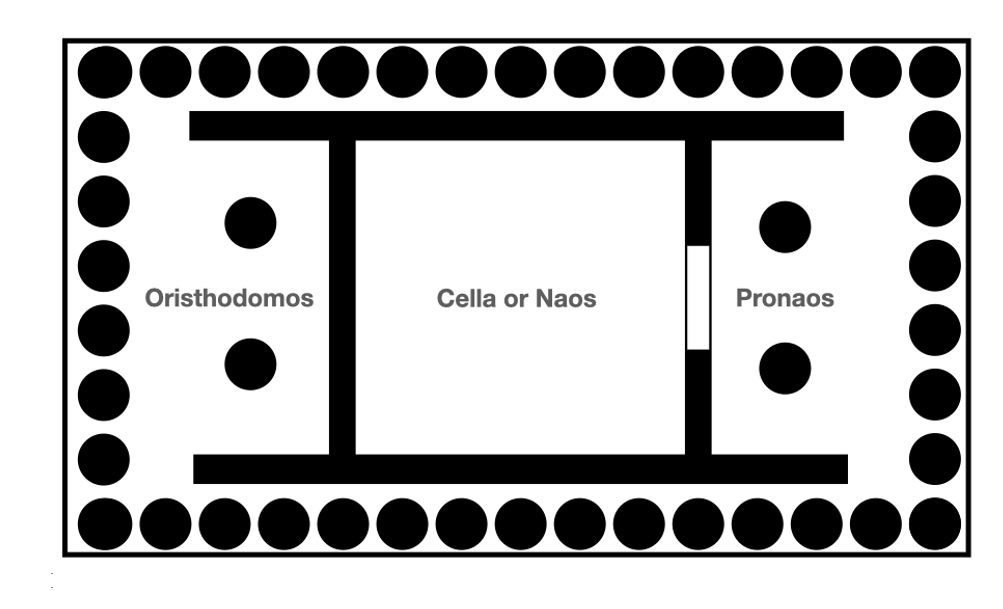

The inner rooms consist of a pronaos, which is a vestibule at the front enclosed by a portico, an inner chamber named the cella or naos, accessed from the pronaos, and an opisthodomos, which is a rear room or porch meant to balance the pronaos (Figure 7). The use of the opisthodomos was not standardized in antiquity but often had the most restricted access (for example it was used as the treasury in the Parthenon in Athens).

Figure 7: Depiction of the Pronaos, Cella (Naos) and Oristhodomos. Diagram by Jess Taylor.

Vaulted Cellar

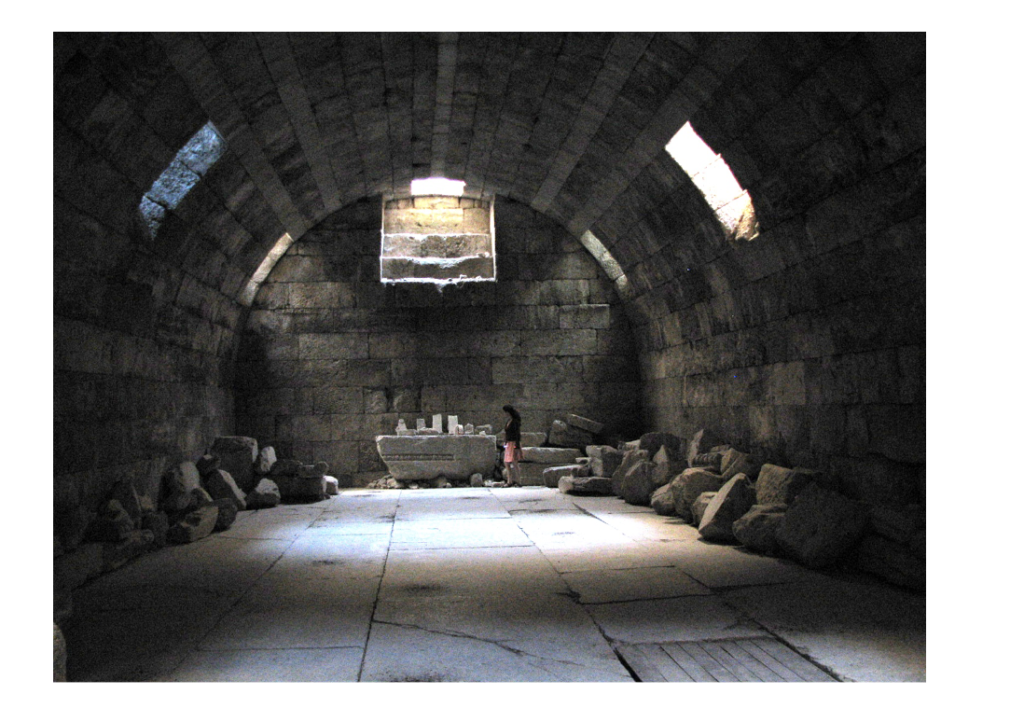

Most unusual at Aizanoi is the combination of a temple erected on an elevated platform that included a “stepped” stylobate (Figure 5) overlying a vast vaulted cellar (Figure 8). Nothing similar has been found in Asia Minor.

Figure 8: Vast cellar beneath the Temple of Zeus, Aizanoi. Photo by Jess Taylor.

Access to the cellar was through a staircase located in the opisthodomos. One would enter from the peristalsis, or colonnade, and pass between two ornate columns of the opisthodomos with their Roman composite capitals (comprised of a combination of Ionic and Corinthian capital styles) (see Figure 9 and Figure 10).

Double Sanctuary of Zeus and Cybele (Meter Steynene)?

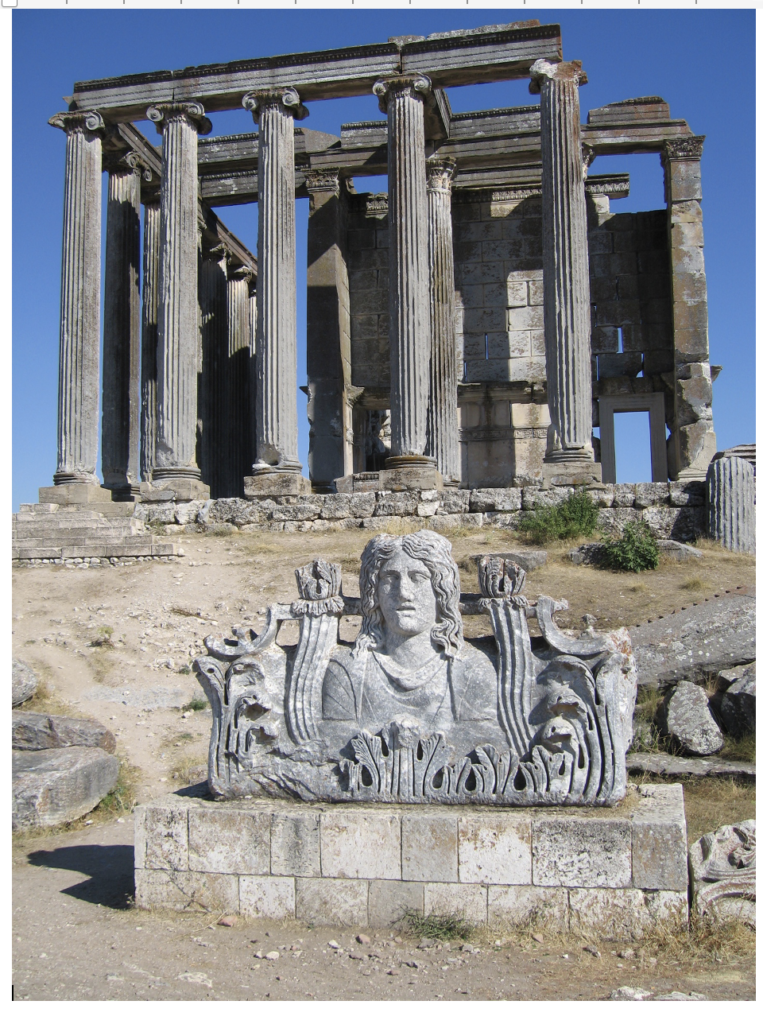

A large roof decoration (akroterion) from the northwest gable, on view in front of the temple near its place of discovery, depicts the bust of a female figure and was interpreted as a sign that the temple was dedicated not only to Zeus, but also to Cybele (Figure 9).

Earlier research postulated the cellar, which underlies the full length of the pronaos, cella (naos), and opisthodomos, was the cult room for the Anatolian goddess Cybele, who was worshipped in Aizanoi as Meter Steynene.

More recent investigation indicates that this earlier idea of a double sanctuary for Cybele and Zeus is unlikely, and the impressive cellar could have served as an oracle or as a storeroom for the harvest from the temple properties.

Figure 9: Roof decoration, possibly of Cybele (Meter Steynene), situated in front of the temple looking from the north towards the opisthodomos. Photo by Rachel Dinno Taylor.

Figure 10: Detail of the Roman composite capitals of the opisthodomos located behind the Ionic capitals of the peristalsis. Note the metal gate on the lower left marking the entrance to the cellar. Photo by Rachel Dinno Taylor.

A Hybrid Temple: Roman and Greek

The Aizanoi temple of Zeus exhibits a mixed or hybrid set of Roman and Greek temple features (Figure 11).

The Roman traits include a high podium with stairs approaching from one side only, monolithic columns (as opposed to drummed), the interior composite capitals in the opisthodomos and the pseudodipteros layout.

The Greek features include the Ionic capitals, the “stepped” stylobate residing on top of the high podium and the pronaos – cella / naos – opisthodomos inner room layout.

To date, the cellar feature is too rare to be categorized.

Figure 11: A hypothesized depiction of temple of Zeus at Aizanoi with a view towards the pronaos (looking south). Depiction by Franck Devedjian, Paris, 2019.

Worth A Journey?

The Aizanoi archeological site possesses great variety including functional Roman bridges, baths, commercial buildings, a stadium, and a theater. The Temple of Zeus is well preserved, displays a mix of Roman and Greek style and is especially unique with its vaulted cellar. And given the fact that the site is undergoing active excavation and restoration, a trip to Aizanoi is highly recommended!

Figure 12: One current use of the Roman baths. Photo by Rachel Dinno Taylor.

References

Aizanoi

- Aizanoi Çavdarhisar Guide, Donmez Offset – Muze Eserleri Turistick Yayinlari, Ankara 1998

- Unesco.org – Aizanoi Antique City

- Republic of Turkiye Ministry of Culture and Tourism – Aizanoi Ancient City

- Dailysabah.com – Ancient city of Aizanoi, home to Zeus’ Temple, to be restored, 2020

- Hypothesized Aizanoi Temple Depiction by Franck Devedjian 2019

- Hadrian / Aizanoi Coin

- 2021 Aizanoi Coin Hoard

Greek & Roman Temples

- Ratté, Christopher, et al. “An Early Imperial Pseudodipteral Temple at Sardis.” American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 90, no. 1, 1986, pp. 45–68, page 61 reproduced here by permission.

- Illustrated Dictionary of Historic Architecture, Edited by Cyril M. Harris, Dover Publications, New York 1983

- Vitruvius Pollio – The Ten Books On Architecture, Harvard University Press, 1910

- Worldhistory.org – Plan of the Parthenon

- List of Ancient Greek Temples