By Kristine Wendt –

One of the most elusive art historical biographies belongs to Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. Having pieced together his biography from police records alone, historians have classified Caravaggio as violent, irascible, and quick to draw his sword. Moreover, surviving contemporary biographies, covetous and biased, have further skewed scholarly views, even suggesting the artist was an atheist and obsessed with death and decapitation. Most significant are the claims that Caravaggio’s darkness in his personal life was the catalyst in his use of the blackness so famous in his latter religious narratives.

Modern historians have also introduced Caravaggio as a belligerent and out of control man who had the personality of a psychopath. They have drawn these conjectures from examinations of his police records and the frequent encounters he had with the authorities; in doing so however, historians have constructed a biased and unjust personality profile for Caravaggio that is not far off from the biased accounts of his own contemporaries. There is an acknowledged lack of documentation that addresses his oeuvre, therefore making an accurate personality assessment extremely difficult to qualify. Scholarship has held fast to the idea that Caravaggio’s darkness in his paintings was a projection of the darkness in his personal life. This thesis argues against that theory by presenting evidence of his true character and explores not only artistic decisions for the darkness, but metaphorical and spiritual ideologies this darkness suggested. This is acutely notable in the above double psychological 1609-10 portrait of himself as a young David disgusted with himself as Goliath, the giant he had become.[1]

The study of Caravaggio’s paintings, explicitly his transition in style, is an integral part of understanding him as a man. It is crucial to establish the multifaceted reasons for Caravaggio’s increasing inclusion of dramatic chiaroscuro and densely black backgrounds especially in his late paintings. Despite this importance, the field of art history has neglected full exploration and analysis of Caravaggio’s darkness. Moreover, scholarship to date has not considered his darkness as a parallel to Renaissance ideals and Counter-Reformation demands for sacral art. My analysis extends beyond any existing research on Caravaggio’s darkness and considers the complex psychology underlining his depiction of it, also immersed in the most profound biblical contexts. Caravaggio was all too aware of himself as a sinner, and once he did not perform ablutions at the door of a Sicilian church because he said all his sins were mortal.

Before we examine Caravaggio’s persona through the scope of his masterpieces, it is equally important to look fastidiously at the artist in the cultural context of the Cinquecento and Seicento. At the turning of the seventeenth century, Rome was in a state of religious turmoil. During the Counter-Reformation the Catholic Church reorganized its doctrines and engaged in a counter attack against the emergence of Protestantism. A new art was sought with the explicit goal to recommit the populace to Catholicism. After the close of the Council of Trent’s 25th session, the tradition of sacred art had been altered. [2] In contrast to the once highly accepted style of Mannerism, the new doctrine formulated by the Church advocated Gabriele Paleotti’s theology and his predominant view that nature, above all things, was the purest form of truth. Thus, the new decrees forbade highly idealized beauty, exaggerated heroic figures, and the depiction of illusionary landscapes. Artists were to create sacred images based on truth as nature presented it, show Jesus and Mary in an age appropriate association, and avoid the addition of elements that merely boasted the artist’s skill or virtuosity. Moreover, the new art must confront the viewer with profound emotion to ensure a sympathetic spiritual experience. The Catholic Church believed a viewer could reach a level of divine spirituality through a painting created by the imitation of nature, which in turn would bring about a recommitment to the Catholic faith.

Concurrent with the refashioning of sacral images, the Catholic Church enforced the Roman Inquisition. The principle responsibility of the Inquisition was to prosecute acts of heresy and witchcraft that included Protestantism. Any other faction that caused a threat to the Catholic Church was also put on trial. It is estimated in Rome, from 1592-1606, the same years Caravaggio resided there, that six hundred fifty-eight public executions were carried out.[3] Like many other Romans, it is likely that Caravaggio was a witness to the public torture and public displays of violence, since he lived in close proximity to the Campo di’Fiori.

The social atmosphere of Rome had its own breadth of violence and brutality. Outside the glorious walls of the papal court and the illustrious courts of the wealthy cardinals, a poverty stricken and dilapidated Rome existed. Poor people roamed the streets begging, stealing, and fighting, including war veterans now out of work and impoverished. [4] The Ortacchio District was famous for its reckless crowds of drunken men, lower class paupers that swaggered in and out of the riotous piazzas, brawlers and bravi who drew their swords freely, and prostitutes who roamed the streets soliciting in the night. Men – soldiers and artisans needed for vast Jubilee projects – outnumbered women by a large degree. This was the Rome Caravaggio knew, and the Rome that he later represented in his religious paintings. Palazzo Madama was located in the Ortacchio District, where Caravaggio resided with Cardinal del Monte in the palazzo for several years, an island haven surrounded by licentiousness and abandon. Rome’s night life appealed to Caravaggio and his attraction may be traced back to the exposure to a similar violent and wild natured street life he was accustomed to in Milan in his youth when Spain oppressively ruled Milan against the will of the resentful people. Caravaggio spent four years in an apprenticeship in Milan where he would have been witness to the unruly nature of the city’s lower classes trying to survive after debilitating plague. [4] In this regard it is possible that as a teenager Caravaggio developed an appetite for adventure and a misguided idea of the law, also without a father figure since his father Fermo Merisi died during a plague year in 1577.[5]

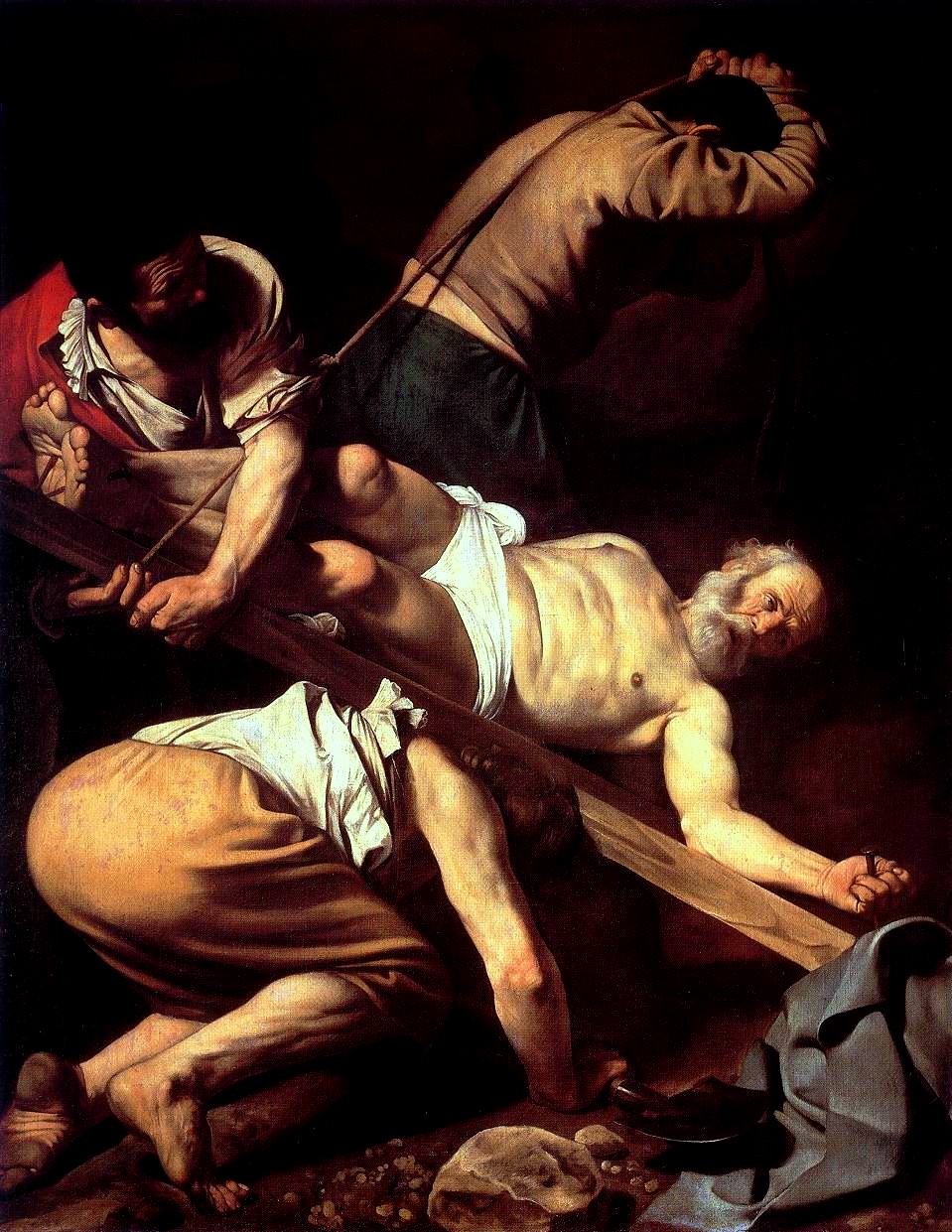

In Rome, Caravaggio was notorious for keeping company with some who could be called neer-do-wells or mostly unemployed bravi, and his free spirit led him to numerous confrontations with the law. It wasn’t long after his arrival in Rome that Caravaggio became notorious for swaggering around town with illegal weapons at his side. Even though he tried to claim being fully genteel through his mother Lucia Aratori, a minor gentlewoman, the absence of a license to carry a sword – a gentleman’s right – was a catalyst to his numerous arrests in conjunction with his unpredictable bellicosity. Together with the religious turmoil, the brutality of public executions, and the violence of Rome’s street life, it is plausible that Caravaggio’s antics were more mischief than acts of a sadistic psychopath. An evaluation of his artworks further may reinforce the supposition that Caravaggio was more often a sensitive, humble man who was deeply religious and had profound humility towards the poor and suffering if not always to heavy-handed authority. Police records tell us that he was an arrogant, hot tempered, malicious man with no regard for the law or people in general. His paintings tell us otherwise, with great empathy for the poor and for the humble people of the street. Pride is not so easy to find in his canvases but suffering is. His Crucifixion of Peter (1601) is not about triumphant hope but rather normal faith and doubt in the acute presence of suffering of an old man.[6]

The Saint Matthew series marked an extraordinary transition in Caravaggio’s style. The once vibrant and warm colors he used vanished in his mature religious works. The innocence once apparent in the figures disappeared and was replaced with signs of the harsh cruelty of life. Caravaggio accentuated age marks and the remnants of adversity are apparent in the faces and musculature of these figures. The soft backgrounds were replaced by the heavy application of black and strong use of chiaroscuro to thrust the figures into the foreground, where they protrude into the viewer’s personal space. Walter Friedlander postulated that a personal struggle may have been the catalyst for such a change “The marked change in the character of his expression might be taken as an indication that something happened, in his outward life or his inner experience, which influenced and altered the natural development of his personality, but we have no evidence as to what it might have been.” [7] Though it is probable that Caravaggio had deep personal adversity at this stage, I don’t propose that a negative event in his personal life, or the assumption he had a personal darkness, caused the change in his technique. I argue the radical shift in his style was in direct response to his introduction and belief in Gabriele Paleotti’s Discorso and the theology of the Orations. In addition, Caravaggio made alterations to his style for aesthetic and practical reasons that better suited the Discorso’s mandates for sacred art.

During his residence at the Palazza Madama and through his new church patrons, Caravaggio presumably was introduced to the Circle of the Oratory and the writings of Gabriele Paleotti. It is essential to consider Caravaggio’s religious style shifted when he became familiar with the theologies of Paleotti, and particularly, the Catholic Church’s demands for sacral images. This theory can be reaffirmed by examining the parallels between Paleotti’s texts and Caravaggio’s transition in style.

In 1582 Paleotti released his Discorso which outlined his principles for sacred imagery. He discussed the importance of a tangible presence in sacred painting and the depiction of naturalism. He declared nature the ultimate form of truth and images were more powerful than words because they could educate the illiterate. Paleotti’s theology stated the painter’s job was to reach and educate the common man. His principles affirm Art’s function was to excite and stimulate profound emotion in its viewer and to reinforce devotion to the Church. His Discorso fulfilled the visions of what the church expected art to achieve. Paleotti’s most emphasized point was that the role of painters was to imitate nature. In this case the evidence is clear that Caravaggio’s point of view on art, as well as his uncompromising depiction of nature, derived in part from Paleotti’s theology.

A related connection between Caravaggio and Paleotti can also be sustained from the examination of his circle of patrons. In 1595 Caravaggio relocated to the Palazza Madama, the house of Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte. In the same year, del Monte was appointed co-cardinal of the Accademia di San Luca, alongside Gabriele Paleotti. Moreover, the 1627 inventory of del Monte’s home further informs us that Caravaggio was aware of Paleotti’s texts. Del Monte owned hundreds of books, among them various theological texts and discourses including Paleotti’s. [8] Caravaggio had access to the Cardinal’s library and these books, although not stated explicitly in records; a related connection can be made. It is also highly probable Caravaggio was introduced to Paleotti by the Cardinal. In this regard it can be substantiated with sufficient certainty, that Caravaggio was associated with the circle of the Oratory, in some capacity, and educated in Paleotti’s Discorso on some level.

In 1599 Caravaggio painted The Calling of Saint Matthew and The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew. It is in these paintings that the drastic use of chiaroscuro became dominant and remained a signature characteristic throughout his work. These two paintings set the precedent for Caravaggio’s religious oeuvre for the remainder of his life. Conversely to his early work, such as Cardsharps, Caravaggio eliminated all exuberance from the faces. His backgrounds previously shaded with soft gradations and lighter values were now engulfed in black, ambiguous, and cold. His heavy application of chiaroscuro provides relief to the figures making them appear more realistic than life. The austere concentration of one light source juxtaposed with the deep black, thrusts the figures into the frontal plane, invading the viewer’s space. The viewer has no choice but to react to such drama. It is plausible Caravaggio used black incessantly to push his figures forward and provide the overall narrative with a more profound emotion than lighter colors suggest.

It is equally as reasonable that he used the darkness and chiaroscuro for aesthetic purposes. It is crucial to examine the environments for which these darker paintings were intended for. [9] To take one instance, The Calling of Saint Matthew and The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew were Caravaggio’s first public commissions, awarded to him by the Contarelli Chapel in the church of San Luigi dei Francesi, likely with the help of Cardinal Del Monte and his circle. Unlike earlier works that hung in private homes which were well lit and exposed to variants of sunlight, chapels of the Seicento were inadequately lit. Moreover, these churches depended on sunlight and flickering candles as their primary sources of illumination. It is likely that Caravaggio was invited to the chapel to first observe the atmosphere, in order to account for the lighting and especially to note the location of where the paintings would hang. With this information it is probable that Caravaggio compensated for the lack of light in the church by making the majority of his canvas black, and illuminating the figures in such a way that even in the most faintly lit churches, the figures would be visible once eyes were accustomed to the pervasive dark, and thus his message clearly conveyed, highlighting his profound subjects rather than the unimportant background.

In relation to Caravaggio’s personality, his awareness of such complex solutions suggest he was a brilliant man with supreme ability to compensate for the absence of environmental light, through his application of color and his use of dramatic light.

The content of Caravaggio’s Saint Matthew series also implies his deep understanding of the human condition, with a strong indication of his personal humility and tenderness, towards the suffering pilgrims and peasants of Rome. Perhaps Caravaggio related to his subjects because he too was once in a dire situation, penniless and despondent, when he first arrived in Rome. His relation to their sufferings however, may also be traced back to his early childhood years spent in Milan and Caravaggio, where he suffered the trauma of losing all the make figures in his life, including his father, when he was only seven. [10] The first two years of Caravaggio’s residence in the city was met with struggle and despair. He moved from studio to studio in hopes of gaining steady employment that would pay him a salary on which he could live comfortably. With no money and no commissions, Caravaggio wore tattered rags as clothes and his hygiene suffered and after being kicked by a horse he was also ill for months, recuperation inhibited by poverty. [11] It wasn’t until 1595 that Caravaggio’s fortune changed. When one has an intimate connection to a physiological and psychological state, such as Caravaggio did to the poor, it is clearly reflected in his or her personality. Moreover, his use of brown and ochre, paired together, reflect a humble and serene Caravaggio, not a violent madman. Brown is deeply penetrating to the psyche and perhaps the strongest empathic motivator on the color wheel and was also symbolic of humility in iconology. Caravaggio’s dominance of black used alongside warm browns, created a profundity that is inexpressible. The combination of brown on black creates a contradiction of emotion; black radiates melancholy and a deep disturbance, while brown reflects a calm and passive aura. The two together make a painting resonate with emotions that pierce the soul of its viewers. It is this concept that gave Caravaggio’s paintings the power to move souls.

It is important to note that Paleotti dedicated a passage in his Discorso to the importance of rendering subjects in a clear and simple fashion. Moreover, he discussed the effects of using a limited palette. “But when a saintly martyr practically materializes in front of your eyes in vivid color… one would have to be made of wood or stone not to feel how much more it intensifies devotion and wretches the gut.”[12] It is this exact theme, and profound effect, Caravaggio’s religious works carry with them. It is for these reasons I suspect Caravaggio was well entrenched in the theologies of Paleotti and had a keen understanding of Christian Mysticism.

Conclusively, when we examine Caravaggio’s surroundings, the environment in which these “dark” paintings were meant to hang in, and his personal experience with being poor and despondent, it is incontrovertible that Caravaggio’s darkness was , in part, the reflection of his highly sensitive, empathetic, and brilliant personality. His incorporation of emotionally penetrating hues and dominating black to emphasize the emotional experience was an intelligent technical approach to painting. Caravaggio’s darkness is not an indicator of a violent madman, rather it was the idea of a marked genius.

[1] Patrick Hunt, Caravaggio. (London: Haus Publishing, 2004) pp. 132-3.

[2] Christopher F. Black, Italian Confraternities in the Sixteenth Century, (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 134-279.

[3] Hunt, pp. 13-16

[4] Helen Langdon. Caravaggio: A Life. (London: Westview Press, 1998), pp. 9-33.

[5] Evelyn S. Welch, Art and Authority in Renaissance Milan, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 169- 241. For further reading on Milan in the Sixteenth/Seventeenth century see Helen Langdon, Caravaggio: A Life (Oxford: Westview Press, 2000), 9-32.

[6] Hunt, pers. comment, 2013.

[7] Walter Friedlaender, ed. Caravaggio Studies. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1955), p. 117.

[8] Zygmunt Wazbinsnki. Il Cardinale Francesco Maria del Monte. (Firenze: Olschki, 1994)

[9] Ed. Rolf Toman, Baroque: Architecture, Sculpture, Painting, (Tandem Verlag, Germany: H.F. Ullman, 2007), 12-18.

[10] Andrew Graham-Dixon. Caravaggio: A Life Sacred and Profane. (London: W.W. Norton & Co., 2010), 51-52.

[11] Giulio Mancini, Considerazioni sulla pittura, 1617-21 (ed. Adriana Marucchi and Luigi Salerno, 2 vols. Rome, 1956-7); Giovanni Baglione, Le Vite de’ Pittori, scultori et architetti, Rome, 1649; Giovan Petro Bellori, Le Vite de Pittori, scultori e architteti moderni, Rome, 1672 (ed. Evelina Borea, Torino, 1976), 27-28, 58-59 respectively.

[12] Gabriele Paleotti, Discorso Intorno alle Immagini Sacre e Profane, (Citta del Vaticano: Libreria editrice vaticana, 1582. and Milan: Cad & Wellness, 2002).