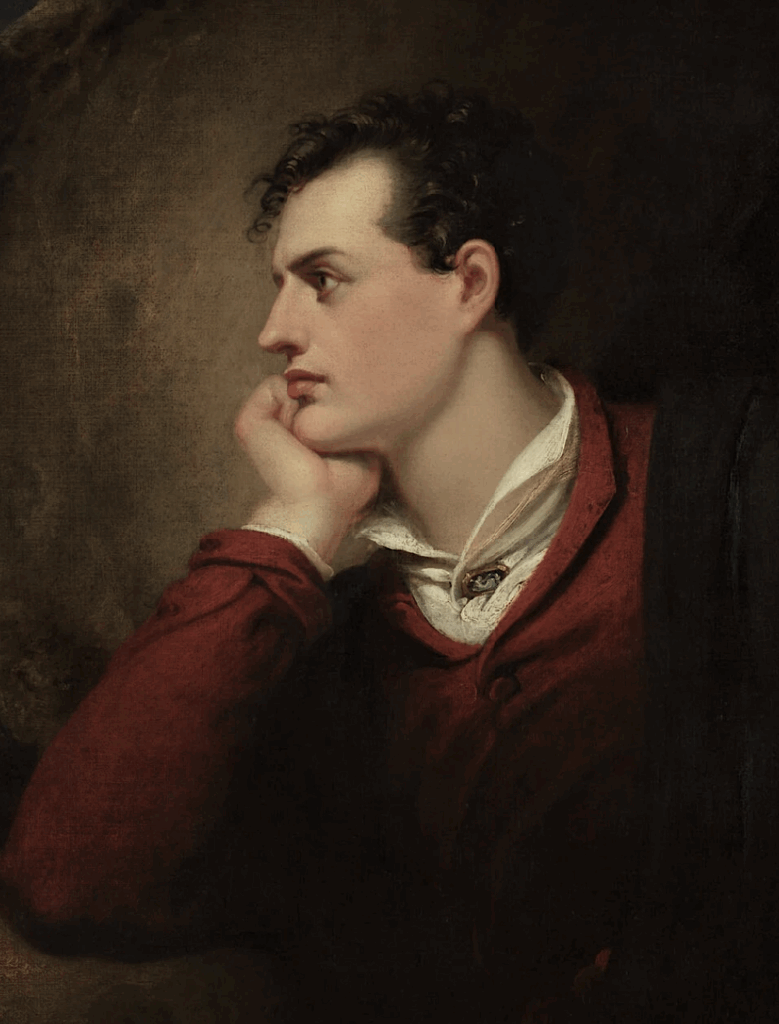

Lord Byron, Portrait detail by Phillips, 1813

By Sara Olsen –

Ovid: Metamorphosis XV.153 : “All Things Change; Nothing Perishes”

George Gordon Byron, whom we can now call an influencer of the 19th century and beyond to the present, was born in London, England, in 1788 to Catherine Gordon Byron and John Byron. Little known at that time was what a bright beam the future Lord Byron would shine on the culture and politics of the Nineteenth Century. He deliberately cultivated a romantic persona and an attitude of insouciance to finances but burned an intense literary flare through all his travels. His somewhat salacious behavior and romantic digressions and his many deep passions often gave him a dubious or at least uncertain reputation. But he forged lifelong friends, who in the end, protected his reputation, and he found a true purpose in his life by supporting the Greek cause of freedom and repatriating artifacts of their culture.

However, Byron had to overcome many obstacles along the way to his eventual success. He was born with a deformed club foot which must have been debilitating to him. His often bankrupt and debt-ridden father (who married for money twice) died abroad when Byron was 3, so he was left in his mother’s care. In 1798, he became the 6th Baron of Rochdale and inherited Newstead Abbey after the deaths of his grandfather and father. There is debated evidence that Byron was likely abused by his nurse in 1799 although the nature of the abuse is mostly lost. He met his half-sister Augusta Leigh, in 1801, who would become a prominent part of his life for awhile and the mother of an illegitimate child, likely his. He was admitted to Trinity College in Cambridge in 1805. He sold the Abbey in 1818 to finance his later travels and the rest of his life.

While at Trinity College, Lord Byron made a lifelong friend in John Cam Hobhouse, who was a member of the Cambridge Whig Club espousing liberal politics. Byron questioned his own writing ability, and apologized as his obliging ward and affectionate kinsman to Frederick, Earl of Carlisle, for his publication of “Hours of Idleness” published in 1807. Byron says of the publication, “Obtruding myself on the world, when without doubt, I might be at my age, more usefully employed”….”I have crossed the Rubicon”. “However, with slight hopes, and some fears, I publish this first and last attempt…It is highly improbable that I obtrude myself a second time on the public” (Byron’s Poems, 2 Preface). He had little self confidence in his poetry at this point in his life. Another lifelong friend met at Trinity was Thomas Moore. From his “Occasional Pieces”, Byron writes:

“My boat is on the shore, and my back is on the sea; But, before I go, Tom Moore; Here’s a double health to thee!

Here’s a sign to those who love me, And, a smile to those who hate; And, whatever ship’s above me, Here’s a heart for every fate.

Though the ocean roar around me, Yet it still shall bear me on; Though a desert should surround me, It hath springs that may be won.

Were’t the last drop in the well, As I gasped upon the brink, Ere my fainting spirit fell, Tis to thee that I would drink.

With that water, as this wine, The libation I would pour Should be peace to thine and mine, And a health to thee, Tom Moore.”

July, 1817.

Byron’s affection and trust in Moore would continue throughout his life. After graduation, Byron moved into Newstead Abby where a maidservant, Lucy, would give birth to his illegitimate child, the first of probably many that Byron fathered. Following this in 1808, possibly as much to avoid collections on his already large perpetual debt as to explore Europe, Byron leaves with John Cam Hobhouse for Portugal and the Mediterranean, the beginning of his adventures abroad and the exploration of his character.

Lord Byron and his friend John Hobhouse traveled to Greece in 1809, where Byron developed an emotional attachment tor ‘dearly beloved Greece’. (MacCarthy, 109). Athens at this time was ruled by a Turkish governor. While there, Byron met 19 year old Andreas Londos, who would become one of the Greek leaders of the War of Independence. Later Byron wrote to Londos, ‘Greece has ever been for me, as it must be for all men of any felling or education, the promised land of valor, of the arts, and of liberty throughout the ages’ (MacCarthy, 110).

Byron would see Londos again on his return trip to Greece and both would become deeply involved in the fight for independence. After viewing, with sad reflections, the wonders and cultural destruction happening in Greece by the unchecked collection of Greek antiquities from the Athenian Acropolis, the Theatre of Dionysius and the Temple of Zeus, Byron was angry. The British and other Europeans, especially Lord Elgin, had been collecting the marble sculptures of the Parthenon for a decade in what he saw as plundering. The loss of many of the hallmarks of Classical Greek culture by the taking of spolia was a pervasive activity of Europeans fueled from an entitlement rationale – although they would see it as deep love of the past – and Ottoman indifference. The collectors also maintained, in an argument Byron thought weak, that British sculptors and architects would benefit from having access to the marbles for instruction, when it was often more likely for self-enrichment. Byron lashed out, ‘I know no motive which can excuse, no name which can designate, the perpetration of this devastation!’ (MacCarthy, 113).

Originally, Lord Byron had called Lord Elgin foolish to be picking up the broken stones of the Parthenon. Many had been blown off the Parthenon in 1687 by the Venetian assault when the turks had stored their gunpowder inside but Elgin’s workers also prized many other marble sections off the temple. However, after seeing the devastation, Byron in his anger, compared Lord Elgin to the rapacious Roman governor Verres whom Cicero had so brilliantly prosecuted. Elgin, like Verres, perhaps thought he had the right to take what he wanted, the right to spoliation. The comparison to Verres was noted powerfully in England. Byron’s “Curse of Minerva” was another vehicle to protest the plundering. ‘Her eyes were filled with tears’ as she was upset about the violation of her temple. The devastation inspired Byron to write the second Canto of his epic Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage which was completed by the time he reached Smyrna and was published in 1812. In it, he again criticized Lord Elgin. The poem became a success and proved a vehicle to express to the British public the deepening destruction of Geek culture.

XI

“But who of all the plunderers of yon Fame, On high-where Pallas lingered, loth to flee

The latest relic of her ancient reign- The last, the worst, dull spoiler, who was he?

Blush, Caledonia! Such thy son could be. England! I joy no child he was of thine;

Thy free-born men should spare what once was free: Yet they culd violate each saddening shrine,

And bear these altars o’er the long reluctant brine.

XV

Cold is the heart, fair Greece! that looks on Thee, Nor feels as Lovers o’er the dust they loved,

Dull is the eye that will not weep to see, Thy walls defaces, thy mouldering shrines removed

By British hands, which it had best behoved To guard those relics ne’er to be restored:-

Curse be the hour when from their isle they roved, And once again thy hapless bosom gored,

And snatched thy shrinking Gods to Northern climes abhorred!

The powerful emotive success of Byron’s words in Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage influenced the British people to disapprove of Elgin’s removal of the marbles from the Parthenon. Much of the British public regarded the Parthenon to be of great historical importance to the culture of Greece. The British Museum, in consideration of public opinion, hesitated to buy the plundered marbles from Lord Elgin. Although the museum did eventually purchase the marbles, the controversy exists today as to whether the marbles should be repatriated especially since the original Greek building still exists and the Greek culture and language remain largely intact. The power of Byron’s words was starting to define his character and formulate his purpose. Later, Byron would return to Greece and again would be a strong supporter of and a voice for Greek culture.

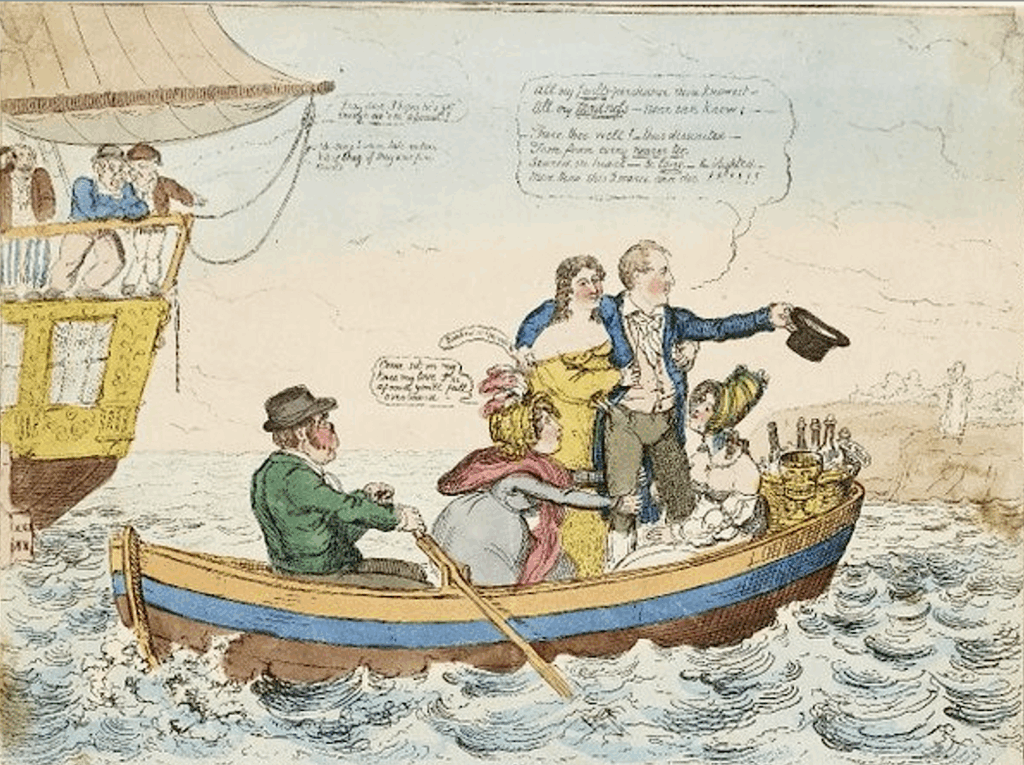

George Cruikshank’s satirical image of Byron leaving England ca. 1816 (image in public domain)

Interrupting his first Grand Tour (1809-11) with Hobhouse, Byron returned to London in 1811. His mother died soon after. Because of his birth and subsequent inheritance of his title, Byron was entitled to enter the House of Lords. Some of his causes in the House of Lords, such as class rights and religious justice, foreshadow some of his writings in Don Juan. He took his place among Whig politicians. However, Byron grew tired of the work of “senatorial duties” and became more interested in his social and amorous life. He had a vision that a poet could move the assembly and make changes. Noble language had power in his opinion…his memories and imagination of Greek oratory seemed romantic and very “Greek”. Byron’s words that “I concede with you in opinion that the Poet yields to the orator” shows how he valued Greek oratory (Trueblood, 31). After Byron’s initial success of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage in 1812, he decided to become a full-time poet and left the assembly. However, Byron’s time while in the assembly fueled his passion for liberty and gave him a deeper understanding of British as well as European politics. He wrote:

“Hereditary Bondsmen! know ye not, Who would be free themselves must strike the blow?”

Thomas Phillips. Lord Byron in Albanian Dress, 1813. Venizelos Mansion, Athens (British Ambassador’s residence) (Image in public domain)

Leaving England again on his second Grand Tour with friend John Hobhouse in 1816, he wrote reminding his readers to be true to the finest traditions of humanitarian ideals. These particular cultural beliefs ultimately appealed to the upcoming younger generation during the 1830’s and 1840’s.

“I’ve no great cause to love that spot on Earth, Which holds what might have been the noblest nation;

But, I owe it little but my birth, I feel a mix’d regret and veneration

For its decaying fame and former worth. Seven years

Of absence lay one’s old resentment level. When a man’s country’s going to the devil.”

When Byron began to cultivate what critics call the “Byronic Hero” phase of his life, his popularity increased somewhat although he was considered ‘Mad-bad and dangerous to know’ as stated by Lady Caroline Lamb in 1812. She later had a “tempestuous affair” with him (Steffan, intro. VI). Meanwhile, Byron’s other half sister Augusta Leigh gave birth to Medora, Byron’s child. Byron married Annabella Milbanke in 1815, and also had a daughter Ada Byron Lovelace, who seemingly never knew her father and yet became a famous mathematical in her own right. It was the 1813 publication of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage that made him a famous figure in London, popular at parties and drawing rooms filled perhaps at times with swooning women due to his very handsome face and his known amatory proclivities. Purportedly when in Rome in 1817, Lady Liddell told her daughter “Don’t look at him. He is dangerous to look at.”

In 1816, Lady Byron had separated from Byron probably because of his highly-publicized scandalous behavior (as well as his possibly sexual ambivalence), and this year Byron left England for Europe again. He traveled to Belgium and the Alps of France and Switzerland and spent time near Geneva with Percy Bysshe Shelley and Mary Godwin Shelley along with Claire Clairmont, half sister of Mary Shelley, who gave birth to Byron’s child Allegra. Byron went on to Rome Italy, then variously to Venice, Ravenna and Pisa. His daughter with Clair Clairmont, Allegra died in 1822 and Shelley also died in 1822 by drowning. Byron went on to the East with Hobhouse.

Arriving in Constantinople a second time (first visit on 1810) for a longer sojourn, Byron was now much impressed by the joining of the new and ancient. An English resident recognized Byron by his lameness and later published in New Monthly Magazine in 1822 his account of him as seen in a shop “selecting pipes, wearing a gold embroidered scarlet dress uniform…an ostentatious, yet vulnerable figure with his remarkable delicate features which would have given him feminine appearance but for the manly expression of his fine blue eyes. Taking off his cap, he had curly auburn hair and uncommon beauty of his face” (MacCarthy, 120). The duality of Byron’s personality and ambiguous sexuality stayed with him throughout his life. He was attracted to both women and men (or young boys) and vice versa.

While in Constantinople, Byron and Hobhouse explored some of the colorful but poor ‘low life’, learned the differences in the Whirling Dervishes -some mystics and some howling- and saw near naked wrestlers, behavior certainly to be disapproved of in England. Although Byron would decry the Turks occupying Greece in the last period of life while he was fighting for the Greek independence, he writes in Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage that “the Ottomans, with all their defects, are not a people to be despised in that they have a good educational system, honesty in financial transactions, and sophisticated culture” (MacCarthy, 122). Byron, years later, ‘could not empty my head of the East’ (MacCarthy, 124).

Lord Byron’s poem “Don Juan” was a war on the word ‘cant’, meaning shallow sentiment and hypocrisy. The public identified Lord Byron as a prototypical “Don Juan” amid the feeding frenzy when Lord and Lady Byron separated and Byron left England, actually forever. People were alarmed by the immoral liberties in the poem, but even Shelley admired Byron’s genius, for the immortality of nearly every word. Byron drew on his phases of the Grand Tour, his years in England, the scandals of 1816, and the fact that post-Napoleonic Europe restored reactionary monarchies and new repressions. Byron continually tested literary conventions with satire on public issues. He played it as autobiographical verse. Byron wrote to his friend, Thomas Moore, in August, 1822, that he was “changing the poet into a warrior of the pen”…the battle must be fought; and it will be eventually for the good of mankind” (Steffan, xiii). As in the opening stanza of Byron’s epic, he makes to clear that:

“I want a hero, an uncommon want, When every year and month sends forth a new one.

Till after cloying the gazettes with “cant”, The age discovers he is not the true one.”

However, Byron’s Don Juan is the contemporary but controversial “new” romantic hero — for the most part essentially good hearted, forever young and perpetually innocent (or naive) character. Byron’s Don Juan persona that he himself followed in his life never really changes nor does his character develop. The poem becomes like a situation epic (Steffan,xiii). The character of Don Juan has a wide range of levels, and Byron has him performing with Byronic flair and speaking Byron’s poetry. The sales of Don Juan were brisk. Lord Byron was a celebrity and a legend, which could be either helpful with his political views because of his popularity or be a detriment because of the often negative judgement against him by the more conservative elements in society, including the Church of England. In Don Juan the hero figure is mostly patterned after Lord Byron himself, full of mystery, passion and sins. Other Don Juans more akin to one like Mozart’s earlier Don Giovanni (1787 libretto mostly by Lorenzo da Ponte ) were possibly more predatory and more morally bankrupt. Byron’s may be driven by romantic liaisons that were not so lopsidedly macho.

Yet Byron’s Don Juan narrative was “shockingly new and was an assault on shallow sentiment which was tinged with hypocrisy (Steffan,Viii). Much of the British reading public loved it, perhaps as an escape from daily life, as did Percy Shelley, his contemporary, who commented on the “building up of drama” as a positive element. Everything was fair game from Kings to Spanish maids, Greek pirates, Russian armies, British lords and ladies and his own life (Steffan, intro X). Byron was making a name for himself and was applauded for his poetry, and even asking for indulgence over his transgressions.

Richard Westall, Lord Byron, 1813, National Portrait Gallery London (image in public domain)

However, Byron, in his disgust for Lord Elgin, did worry that some of the stanzas he had written for Don Juan about Elgin might be suppressed by his publisher, John Murray. Byron asked his friend and literary agent, Thomas Moore, to retrieve the stanzas so they would not be suppressed and to give them to John Hunt for publishing. Hunt then published them in 1822. The public, weary of war in Europe, relished the adventures of Don Juan in which there was passion as well as subversion, pleasure as well as damnation, both lust and love, and finally, a lopsided adoration by the readers. Byron quipped in his final days that he hoped had many more Cantos to go in the Don Juan of his life as well as in verse.

In July 1823, Byron left Genoa for Greek Cephalonia, landing in August at Argostali, then sailed on a Greek ship Mistico, avoiding capture by the Turks, to Missolonghi, Greece, in late December or early January, 1824. Meeting up again with his friend, Andreas Londos, who was very much involved in the liberation effort, Byron then joined the forces in Greece, taking charge of a brigade. Lord Byron however developed a fever – likely form either malaria or possibly typhus soon after and died on April 19, 1824, soon becoming a Greek national hero. His “martyrdom” for Greece became a symbol of patriotism. He did not fail in his devotion to the Greek culture. Byron’s body was taken back to England where he was buried in the family plot near Newstead Abbey, his family home. Then, 145 years later, his remains were moved and buried in Westminster Abbey.

Missolonghi in engraving – later from 1888 (image in public domain)

From Byron’s birth, family life and his inheritance; to his university experiences with friends; to his travel and time in politics; to his affairs, both female and male; it is evident that Byron was searching for his true identity and purpose as a poet and as a person. Lord Byron’s success and acceptance as a political voice and poet in Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage coupled with his affairs in love and lust especially associated with his narrative and somewhat autobiographical poem Don Juan resulted in Byron emerging as a great Romantic poet whose voice reached many in the turbulent times of Europe. With confidence in his identity as a poet, Byron eventually returned to Greece to find another purpose in life of becoming a hero for a just cause, in this case Greek independence from the Ottoman Turks. He had transformed into a great Romantic poet, shaped by his past and experiences and his poems into becoming a needed voice for freedom, human rights and cultural preservation. Before his death in Missolonghi, on his birthday, January 22,1824 in Greece, he wrote:

“On this day, I complete my thirty-sixth year: Tis time this heart should be unmoved

Some others it hath ceased to move, Yet though I cannot be beloved, Still let me love.

6

The Sword-the Banner-and the Field, Glory and Greece around us see!

The Spartan borne upon his shield Was not more free!

7

Awake! (not Greece-She is awake!) Awake my spirit-think through whom

Thy life blood tracks it parents lake And then strike home!

9

If how regret’st thy youth, why live? The Land of honorable Death Is here- up to the Field! and give Away thy Breath.

10

Seek out-less often sought than found, A Soldier’s Grave-for thee the best,

Then look around and choose thy ground And take thy Rest. ” (Stafford, 664-665)

Byron died at age 36 in Missolonghi. Attending doctors thought he suffered a high fever from a probable malarial relapse, but his adherents saw his death as Byron essentially becoming a martyr for the heroic cause of Greek independence from the Ottoman Turks. Against his wishes, his loyal friends, Thomas Moore, John Murray and John Hobhouse burned his memoirs to preserve his reputation and legacy. It is disappointing to not have those personal musings, but it was probably the right decision.

Epilogue

Ovid: Metamorphoses XV. 871-9 “Now my work is finished… I will live forever”

Lord Byron’s influence in the years following his death in 1824 were slow to take hold in Britain, but thanks to a better understanding of his ironic and satiric analyses in his more political writings, the “movement for nationalism with the spirit of ancient liberty helped effect a change of perspective” especially during the High Victorian era (Trueblood, 199). An older contemporary, William Blake, along with later writers such as Ruskin and Morris as well as G. B. Shaw in some ways shared some of Byron’s vision with their own passionate commitments. Later, also, W. H. Auden and George Orwell subscribed to Byron’s Liberal ideas. Byron with his success in Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage brought with it his advocacy of political freedom. Through his writings, the Byronic Hero, or ‘Tower of Strength’, encouraged people to rise up against oppression in countries across Europe. This feeling did not die with Lord Byron, he was viewed as the law-giver of revolutionary Romanticism on the Continent” especially during 1815-1848. Everywhere independent or rebellious peoples throughout Europe saw Lord Byron as the ‘Trumpet Voice of Liberty’, the poet-laureate of political freedom” (Trueblood, 203). His ability to transform vague ideals into social and political realism, his passion and eloquence made him a champion of political freedom and progressive liberal ideas throughout Europe, and not just to the downtrodden Greeks.

Byron’s posthumous laurel wreath at the Gennadion Library of the American School of Classical Studies, Athens (image in public domain)

While never an official British Poet Laureate given his religious independence and skepticism, Byron was posthumously “wreathed” ostensibly by decree of the Greeks via King George in a putative wreath made by Greek women in 1824; this wreath was placed on his funerary catafalque and eventually ended up in the Gennadeion Library of Athens at the American School of Classical Studies where it rests today on view in the library’s museum. (Hunt, 2009) Byron also has a monument in Poets Corner of Westminster Abbey, not an easily agreed-on monument since he was considered a rebel and possibly agnostic by the Church of England at the time. But his legacy of advocacy for Greek antiquities continues.

Even today, the controversy of returning the Parthenon Marbles is being debated in a ‘storm of controversy’ as to whether the British Museum should return the artifacts to Greece. Byron’s fierce cause to restore Greek culture has lighted fires across the United States, too. The question of provenance, repatriation and what guidelines should apply have prompted rules and regulations or frameworks to support legal responsibilities. For example, the Archaeological Institute of America has initiated a Code of Ethics for the collection of artifacts and protection of provenance. Recognizing the stakeholders, and preserving the context in collecting is essential for establishing ownership and is essential in preserving culture. UNESCO has also issued guidelines for establishing provenance. Museums as well as archaeologists, collectors and collection owners need to do their due diligence to investigate provenance. There are also legal challenges as well as the ethics of antiquities trafficking to address.

Fortunately, there are also positive instances of museums working to preserve cultures that might otherwise be lost because of war, deterioration or looting by safekeeping them and by working with the peoples of a culture to preserve what they have now, preserving with the approval of the stakeholders. Curating items and displaying them safely with respect to the culture not only can protect, but also can educate. A prime example is in the newly renovated Michael C. Rockefeller wing at the Metropolitan Museum of New York and its collection of work from Africa, Oceania and the Americas, wherein the Papua, New Guinea exhibition has been established by working with the people of Papua to respectfully preserve their heritage and to include them in forming their exhibit. Left in situ, most items probably would have deteriorated. This exhibit reflects Byron’s idea of preserving the soul of a place. Lord Byron’s passion, poetry and dedication to the cause of personal freedom and cultural rights have lingered long after his death in Greece over 200 years ago, and will most likely live on for decades to come. Both diplomat and writer, Sir Harold Nicholson, wrote Byron: The Last Journey in Italy in 1923 from the Villa Medici in Fiesole and knew well Johannes Gennadius, the Greek Minister in London 1910-18, whose library is now in Athens as mentioned above where Byron’s laurel wreath resides. Nicholson acerbically wrote, among many other things, “Lord Byron accomplished nothing at Missolonghi except his own suicide, but by that single act of heroism he secured the liberation of Greece” (Nicolson, viii).

Byron has become one of the most influential poets of the Romantic Period to leave this mark on cultural and political viewpoints during his lifetime as well as on viewpoints today. Thankfully, the power of Lord Byron’s pen has created a flutter that has changed outcomes over time…just another manifest of the Butterfly Effect.

Sources:

AIA, Archaeological Institute of America. “AIA Statement of museum Acquisitions and Loans of Antiquities and Ancient Art”, March, 2006. Access 3/15/25.

AIA Code of Ethics. 44 Beacon St., Boston, MA. rev. January 8, 2016 meeting.

Byron’s Poems. “To the Right Honorable Frederick, Earl of Carlisle, Preface”, Lord Byron. Author’s personal collection.

Eisler, Benita. Byron, Child of Passion, Fool or Fame, Vintage Books, Division of Random House, Inc., New York, NY. 1999.

Gerstenblith,Patty. “Meaning of 1970 for the Acquisition of Archaeological Objects”, Journal of Field Archaeology, Vol. 38.4 (2013) 364-373, Tayler and Francis,Ltd., https://www.jstor.org/stable/24408714. Access 4/15/2025.

Hunt, Patrick. “Re-Grafting Apollo’s Laurel Bough: Byroniana at the Gennadeion and Revival of Tradition.” Akoué 60-61 (2009) 7-8. American School of Classical Studies, Athens (GR) and Princeton NJ. (https://www.ascsa.edu.gr/news/newsDetails/re-grafting-apollos-laurel-bough).

___________. “International Law and the Ethics of Antiquities Trafficking”, Stanford Journal of International Relations, Spring, 2010. Access 4/21/25

MacCarthy, Fiona. Byron, Life and Legend, John Murray Publishers, London, England, 2014.

Miles, Margaret. Art as Plunder, Cambridge University Press, New York, NY. 2010.

Nicolson, Harold. Byron: The Last Journey, 1823-24. London: Prion Books (reprint from London: Constable Publishing, 1923) 1999.

Stafford, Fiona. Byron’s Travels, Poems, Letters and Journals, Alfred A. Knopt, ,New York, NY. 2024.

Stauffer, Andrew. Byron, A Life in Ten Letters, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 2024.

Steffan, T. G. E. Steffan and W. W. Pratt. “Don Juan”, Lord Byron, Penguin Books. UK. 2013.

Taylor, Derrick Bryson. “A Collaboration to Revere,’ The Spirits in the Ceiling’”, New York Times, Arts Section, 5/31/2025. Access 5/31/25.

Trueblood, Paul Graham, ed. Byron’s Political and Cultural Influence in Nineteenth-Century Europe: A Symposium, MacMillan Press, LTD., London, England. 1981.

UNESCO. “The Standard for Acquisition of Archaeological Materials”, 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property.