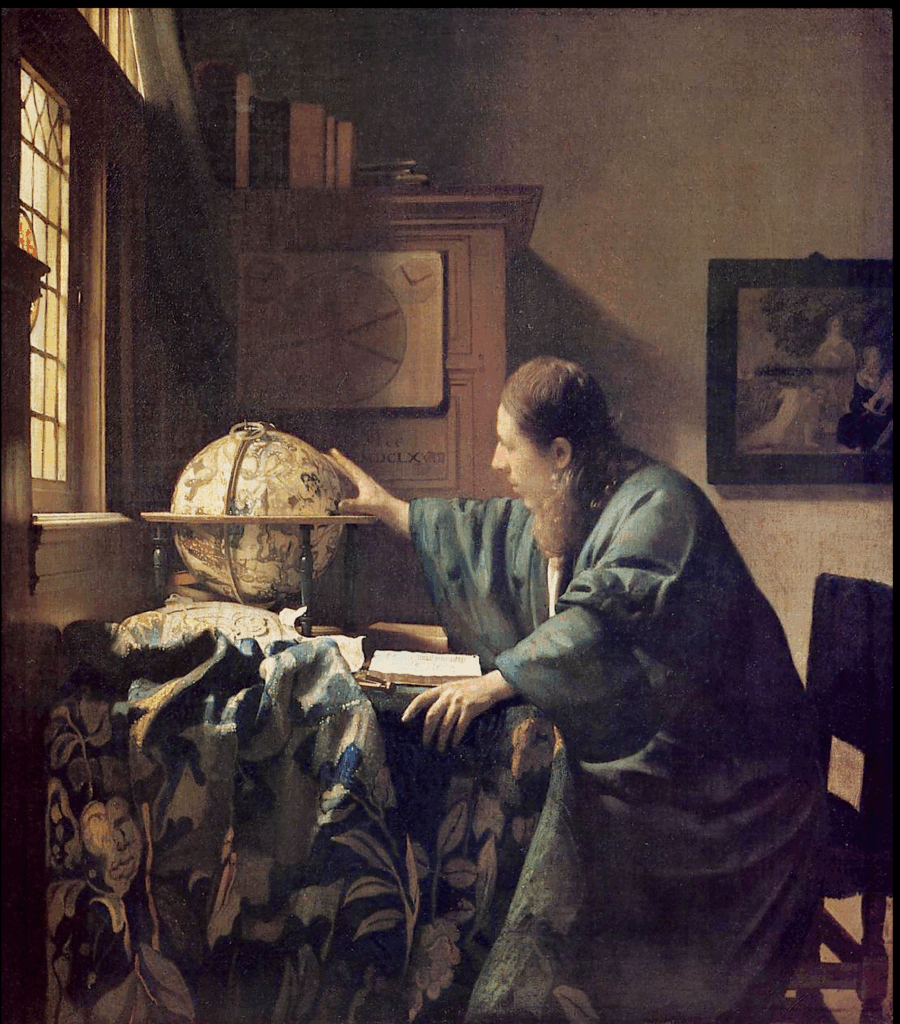

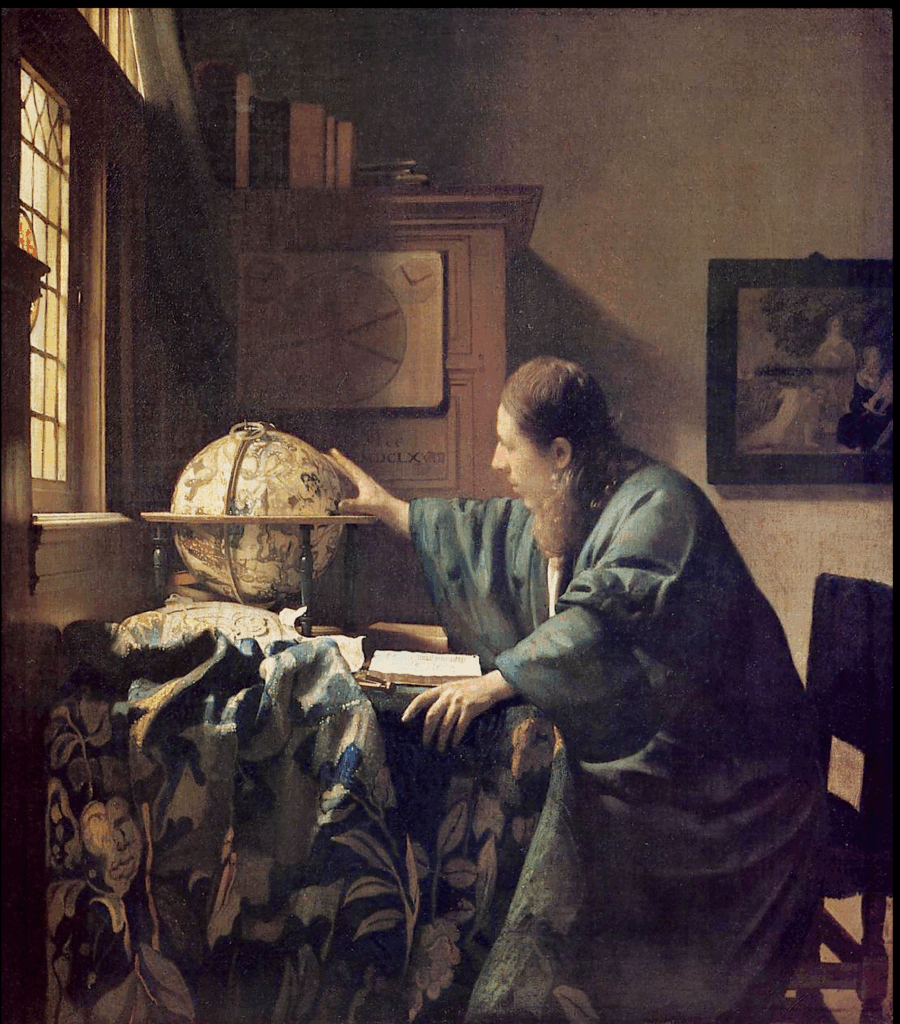

Jan Vermeer, The Astronomer, 1668, restituted to Rothschilds after WWII, then gifted to Louvre (Photo P. Hunt 2025)

By Jann Perez –

Deep questions about the ethics of collecting and also about repatriation of plundered art and antiquities are far more complex than they might at first appear from shallow or cursory approaches. While not always easily answerable, or often with two nearly equal opposing viewpoints, following are a few questions with wide-ranging implications that deserve attention. This brief article does not necessarily expand possible answers to address all viewpoints or ramifications.

1) How complicated is repatriation of art and antiquities when the original stakeholders are long gone (e.g., 19th c. Ottomans selling ancient Egyptian, Mesopotamian or Greek monuments to European powers)? A following question might be, if there are original stakeholders surviving into the modern world, should that help inform repatriation? For example, despite frequent calls for repatriation, most of modern Egypt is not much populated with the ancient stakeholders of Ancient Egypt. Clearly, Ancient and Modern Egypt differ greatly in ethnicity and DNA, language, culture and religion after thousands of years. Most of Modern Egypt’s population is of Arab (17%) or North African ethnicity (68%) and its DNA is mainly derived from those groups. Likewise, most modern Egyptians identify as Islamic in religion (~90%) and most speak Arabic by far (~98%). While the modern Copts in Egypt can be identified as closest to Ancient Egypt in DNA and ethnicity, they are clearly Christian rather than followers of Ancient Egyptian gods. So the calls for repatriation of ancient Egyptian artifacts are complicated by these acutely modern differences from antiquity. On the other hand, the people of Modern Greece are mainly similar to Classical Greeks of several thousand years ago in language, DNA and ethnicity (~90%) as well as culture, including mythology (comparable as ancient religion). So it appears reasonable that modern Greece’s calls for repatriation of its lost antiquities are much stronger in authenticity than those of many other sovereign nations whose modern population is almost completely different than its ancient population. Many advocates of repatriating, for example, the 5th c. BCE Parthenon sculptures also add that the original Greek Parthenon temple on the Athenian Acropolis is still standing for the most part in its original location, which may enhance the validity of repatriating. But the most sensible advocates realize that the Parthenon sculptures cannot be exactly replaced in the original temple in their original contexts where they would be mostly unviewable high off the ground by at least 40 feet and in deep shadow above potential viewers who also have to stand considerably distant from the archaeological monument. In 1975, the Greek government began the modern process of cleaning and restoring the Parthenon along with the surrounding Acropolis, carefully restoring much of the Parthenon’s marble stone under architect and archaeologist Manolis Korres from the 1990’s until 2005. Greece finally built the new Acropolis Museum which opened in 2009 to house the Greek remnants while hoping for the return of the remaining sculptures in London and elsewhere (Paris, Copenhagen, Vienna, Wurzburg, etc). It is telling that only the Vatican under Pope Francis in the last decade returned its Parthenon fragments. There is certainly no easy answer to this particular international dilemma (more to follow in the next query).

The Parthenon with Manolis Korres’ restoration, Acropolis view from southeast (Photo P. Hunt 2016)

2) How does collecting antiquities stimulate looting (basically an economic application of the law of supply and demand) ? If there is demand for antiquities, the market will supply it because the looters see financial reward and profit from looting. If dealers or potential collectors fail to conduct due diligence regarding the true provenance or history of the objects, mainly if the trail of ownership is either absent, murky or not genuine, then the other sad result is that site history and individual context are lost, likely forever, since the thieves rarely record their looting because of a logical fear of being liable. Major art auction houses and museums in London, New York and Los Angeles have been under the microscope about purchasing stolen Greek or Etruscan antiquities, resulting from a long supply chain of site or tomb raiders (tombaroli) to corrupt dealers to museums or rich collectors. The famous Euphronios Krater (ca. 515 BCE), one of the most exemplary Classical red-figure Greek vases, is an excellent case in point. This Greek krater was stolen from the Etruscan site Greppe Sant’Angelo in Cerveteri in 1971. The trail then implicates middlemen purveyors and dealers like Giacomo Medici and Robert Hecht all the way to the Metropolitan Museum in New York which bought the krater in 1972 for around $1 million. The haunting question is whether or not or how much they knew about its dodgy recent past. A fascinating book, Peter Watson’s and Cecilia Todeschini’s The Medici Conspiracy (Perseus Books Group, 2007) expansively details this sometimes astonishing story with many photos. Sadly, a disappointing flip side to repatriating this beautiful vase back to Italy from where it was stolen is that viewership in New York from 1972 onward went from an annual average of millions of viewers, then to the Villa Giulia – the National Etruscan Museum in Rome – (where it was returned in 2008) with an annual average of 90,000 viewers and finally to the Cerveteri Museum (where it was returned in 2014) with around 26,000 annual viewers. So in light of the Euphronios Krater’s diminishing visibility, it is no wonder that advocates for keeping the Parthenon Sculptures at the British Museum in London argue not only that these materials were legally acquired – of course, from the Ottoman occupiers, not the Greeks – but that far more of the world will see them for free in London than in Athens. These arguments are all moot. British Museum proponents also argue that Britain will return such objects when France, Germany, Russia and the U.S. also return their thousands of contested objects. So repatriation remains an internationally contentious matter in the 21st century.

Jan Vermeer, The Astronomer, 1668, restituted to Rothschilds after WWII, then gifted to Louvre (Photo P. Hunt, 2025)

3) How many major European and American museums may still own contested pieces taken from Jewish owners by the Nazis but whose provenance mostly disappeared between 1937-1950 ? From 1945 onward – for example with former Jewish art dealer Max Stern’s efforts to recover art he was either forced to sell or leave behind in Nazi Europe – and snowballing in 1998 with redoubled efforts led by the United States, Western governments began to more seriously heed the demands of the survivors of the Nazi attempted genocide of the Jewish people and their culture. This culminated in a worldwide push to reunite them with their looted possessions, most significantly, their works of art. Thousands of art pieces that have been installed in museums around the world after 1945, most notably in Germany, France and the U.S. that have a questionable or absent provenance between the late 1930’s and early 1950’s are now far more scrutinized. Note the above Vermeer painting THE ASTRONOMER from 1688. This was confiscated by the Nazi ERR (Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg) from the Rothschild Family collection along with hundreds of other masterpieces during the Nazi occupation of France and hidden in the Altausee Salt Mine in Austria, but found in 1946 and restored to the Rothschilds, who then gifted it to the Louvre to share with the world.

Cretan antiquities crime ring busted in April 2025 by Greek authorities (Photo courtesy of APNews, 2025)

As of the year 2000, there were close to 30,000 works formerly owned by Jewish families or countries such as Poland that are still in the possession of European and U.S. museums. The laws of repatriation are continually evolving, creating an environment for museums to refuse to share their collections with other institutions due to possible confiscation. The Royal Academy in 2010 had to guarantee Russia that the traveling Russian art collection – including many Impressionist paintings taken from Berlin in 1945, but which were also likely taken by the Nazis from Jewish owners – to be exhibited in London would be indemnified against claims of prior owners. In Vienna, much of the work of Gustav Klimt housed at the Belvedere Palace is closely guarded as some of its original ownership before 1945 is contested.

The number of museums holding contested works is unknown. In 2006 a survey of Nazi-looted art was sent world wide and the response was only 44%. Groups such as the WJRO (World Jewish Restitution Organization) kept sending questionnaires, calling and emailing until the end the year. They received responses from only the large museums in Europe which shall retain anonymity here. Smaller museums in many European countries have mostly not participated by nor returning the questionnaires. A better answer, which is what I attempted to do is: how many contested items are still in the hands of worldwide museums. The Harry Fischer List which was comprised by Nazi art historian Rolf Hershey is the gold standard for the search. Unfortunately, the list contains the item and from whom it was acquired but not always which museums or individuals received the pieces. This list is at the V&A Museum in London and use is limited to credentialed researchers.

A better question could be more narrow: How many museums within the US contain contested art? From the 2006 questionnaire only 5 U.S. museums did not reply, including the Getty and Guggenheim although both have contested items in their collections. This is a quote from Gilbert Luger: “If you now conclude that every museum will have to make their documents available to the public then you have to think again. This is the beginning of a very complicated process focused on privacy and where can you even go to gain access?”

After WWII, there was a mostly invisible scramble by museums, including the US, to acquire Nazi looted art. The rationales may have been to not let German and Russian museums have it all, that many original collectors were dead, and that the documents were likely destroyed (this supposition turned untrue). However one could try to identify or speculate about the psychological terms of acquisition of this looted material, perhaps it is best to describe it as a very competitive but ultimately rationalizing process.

The age of tomb raiders may be a closing window, but organized crime remains noticeably present, often using looted art and antiquities to launder and hide dirty money from drugs, arms and human trafficking. Just in April, 2025, the tip of the iceberg is visible from Crete where an antiquities trafficking ring was busted with possibly millions of dollars in scores of pieces of looted ancient art. The thieves linked to organized crime were shown to be also possibly involved in smuggling arms and narcotics as well, most likely using antiquities for money laundering because it was seemingly less degrading about human life on the surface, since other than how it is acquired, the art market is not as objectionable as arms or drugs or slavery. This last point underscores the idea of caveat emptor : “buyer beware”. Buying antiquities or art without a transparent legal provenance, one that shows not only point of origin and historical context with a full record, means that ultimately the collector is complicit with whatever crimes transpired along the way. Other than in scale, this is really philosophically little different than the Herman Goerings and other Nazis who amassed immense loot from Jews who could rarely cry out from the grave or the gas ovens of Auschwitz.

A lost culture cannot so easily cry out when its legacy is stolen.

Euphronios’ red-figure krater with ‘Death of Sarpedon’, ca. 512 BCE, now back at Cerveteri Museum, Italy (Image public domain)

Sources:

Lynn H. Nicholas. The Rape of Europa: The Fate of Europe’s Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War. Vintage, 1995.

Colin Renfrew. Loot, Legitimacy and Ownership:The Ethical Crisis in Archaeology. Bristol Classical Press, 2000.

Roger Atwood. Stealing History: Tomb Raider’s, Smugglers and the Looting of the Ancient World. St. Martin’s 2006.

Margaret M. Miles. Art as Plunder: The Ancient Origins of Debate about Cultural Property. Cambridge University Press, 2008, esp.

“The Parthenon/ Elgin Marbles Debate: Return or Retain?” Antigone Journal, December 17, 2023

(https://antigonejournal.com/2023/12/elgin-marbles-debate/)

Peter Watson and Cecilia Todeschini. The Medici Conspiracy: The Illicit Journey of Looted Antiquities. Public Affairs-Perseus Group 2007.

WJRO: World Jewish Restitution Organization (https://wjro.org.il/).

“Dozens of ancient artifacts seized in Greek island smuggling raid.” APNews.com, April 24, 2025

(https://apnews.com/article/greece-antiquities-smuggling-crete-police-59b29b3b9aaa9cd403d95526d09e0071).