Giotto’s Navicella, ca 1305, Vatican (see below) public domain

By Timothy Demy –

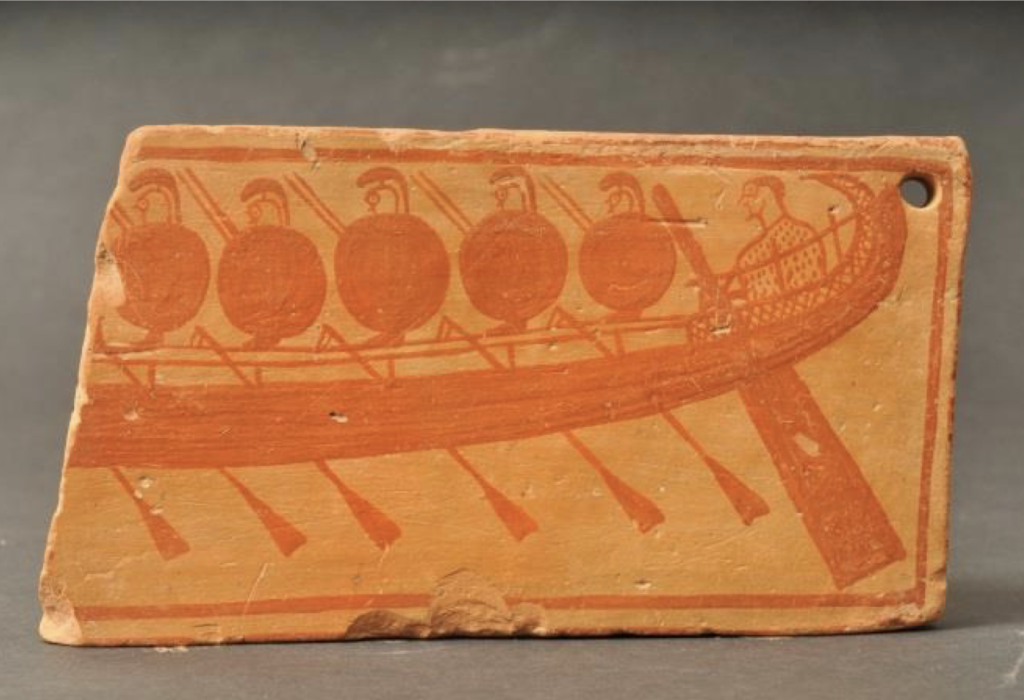

Consider the things one might expect to see in chapels, churches, and cathedrals—stained glass windows, altars, pulpits, pianos, pipe organs, Bibles, hymnals, prayer books, missals, vestments, candles, pews, embroidered kneelers, and a score of other items. What most people probably would not expect to see is a ship model. But if you are in the Mediterranean or Scandinavia or some places in the United Kingdom, and less so in Canada and the United States, such models are commonplace. They are known as “church ships” or “votive ships” and usually suspended from the church ceiling. There are naturally precedents of model votive ships in the ancient world, for example, from Classical and earlier Greece. As gifts to the gods of antiquity, a model of a votive ship was meant to symbolize the vowed request for and / or guarantee of safety for an actual sea voyage of a real ship, as Streuding and others have shown and seen below in the votive Sounion plaque ca. 700 BCE in the National Museum of Athens.

Sounion Votive Ceramic plaque, ca. 700 BCE (from Streuding, 2014)

This ancient votive practice was continued in novel ways into the Christian world, as the much later European examples below show. Because maritime travel was always risky, making a vow and dedicating a model of a ship was a sensible form of divine request for safety of the boat, its merchandise and of course its human crew. If Poseidon or Neptune, etc., were the intended votive deities in antiquity, this was easily transferred to the God of Christianity.

Århus Cathedral, Denmark: Votive ship Unity from 1720 (Photo by Jurgen Howaldt, public domain / Creative Commons)

Thus a votive ship is a model of a ship usually made by a Christian mariner and displayed in a church as an ex voto or votivius (“after a vow”). The models were crafted by seafarers and given to their churches in gratitude and thanksgiving to God for safe return from a perilous voyage. Some were made by the mariner (a common pastime for those with the skills and a unique variety of folk art that frequently were extremely accurate); others were commissioned by mariners. Yet other ship models in churches of maritime communities in Europe were symbols of the congregation being steered safely with Jesus Christ at the helm (a common image in 19th– and 20th-century religious art).

Traditionally facing east toward Jerusalem with the bow slightly raised, votive ships vary in the detail of their construction and sometimes have exaggerated details so they can be seen from below by parishioners and visitors and are more representative of folk art. Others are extremely accurate. Whether in parish churches, cathedrals, or seamen’s chapels, such models are reminders of life at sea, hazards of the sea, and prayers at sea and prayers by friends and loved ones ashore.

Some votive ships are naval vessels and yet others are commercial ones. Most date from the 1700s–1800s, but there are earlier ones as well, and at least one dating from the mid-fourteenth century found in the Maritiem Museum Rotterdam. In an era and regions where the maritime industry was a major economic factor and also an area of naval conflict, there were professional mariners as well as conscripts. Whether warships of naval fleets or fishing boats or trading ships of commercial fleets, seafaring and its vessels were common sights and well-known in coastal towns and villages. In nations where politics, economics, and national prowess were reliant on shipbuilding and seapower, symbols and artifacts associated with the sea would be as commonplace as agricultural symbols, implements of the harvests, and fruit, grain, and wine in other communities and countries. In some coastal towns and villages, church ship models were often carried in procession as part of the annual “Blessing of the Fisheries” or “Blessing of the Fleet.” Prayers for a safe and prosperous voyage, full nets, and naval victory were no different than prayers for a plentiful harvest. For the faithful, prayer and thanksgiving were part of daily life.

Navicella, after Giotto, in the Vatican. Copy in oils made in 1628 of Giotto’s art depiction of 1305–1313 (Image public domain)

There is a long history of nautical and maritime iconography associated with Christianity deriving primarily from the four Gospels in the New Testament and the lives of early followers of Jesus of Nazareth such as the Apostle Peter, a fisherman from Galilee. There is the story of the shipwreck of St. Paul found in the Acts of the Apostles (27:28–28:10); yet there are also stories from the Hebrew scriptures in the book of Genesis, the book of Jonah, and the book of Psalms.

Later Christianity not only has many depictions of biblical stories related to the sea, but also uses nautical terminology in its worship and architecture. Indeed, the nave of a church, the central part of the church where the congregation sits is derived from the Latin navis, meaning ship and referring possibly to either the Barque of St. Peter or Noah’s Ark. If the former, then it was reference to the 1298 mosaic the Bark of St. Peter, commonly known as theNavicella, “The Little Ship,” by Giotto that was commissioned for the Old Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome. The mosaic presents the account of Jesus walking on water as recorded in the Gospel According to St. Matthew 14:24–32 and summoning St. Peter to come to him on the water. The boat depicted is a bark/barque which has a square-rigged foremost mast. (Largely destroyed during construction of the new St. Peter’s Basilica in the 17th century, the work is commemorated in the full-scale copy in oil by Francesco Barretta. As a whole, it represents the ship as the Church, an image found in Latin Christian writings as early Tertullian (150–240 CE) in De Baptismo and Clement of Alexandria (c. 150–215 CE)_ in the Pedagogus (11). In Eastern Christianity, what became the nave was portrayed as the Ark of Salvation in its iconography, deriving from the story of Noah’s ark in Genesis 7–8.

At times, church buildings were sometimes referred to as St. Peter’s Ships and nautical imagery of the anchor was used as a Christian symbol of steadfastness and tranquility. So too did the compass card or compass rose, the circular card attached to the needles of a mariner’s compass on which are marked the 360° of the circle and 32 equidistant points, found in the ship’s binnacle, become a Christian symbol of divine guidance. There are also ship carvings in some medieval churches.

That Christians and seafarers more than a thousand years later would use ship models and art as part of daily worship as well as during holy days and festivals should not be surprising–especially for those whose livelihood came from the sea. Found in nations that were predominately Roman Catholic such as France and Spain as well as in predominately Protestant nations such as Denmark and Sweden, votive models integrated worship and work as part of a unified religious worldview beginning in the Middle Ages. There are fewer extant models in England, a nation rich in maritime history. Perhaps some were lost during the English Reformation–there are records of ships no longer seen. Even so, ships remain in Liverpool, Greenwich, as well as in Scotland in Aberdeen, Glasgow, and elsewhere throughout the British Isles. They are also quite common in Scandinavian churches.

The building of model ships has a much greater history than simply that of a hobby or pastime. In the naval and maritime world, ship modeling had an important purpose. In the ancient world, models were part of burial and votive offerings and occasionally as toys or pieces of art. In more recent centuries, they were part of naval architecture and the precursor to the construction of the ships of all designs and for all purposes—commercial and military. Built to scale, models enabled all involved with the construction and purchase of the new ship to see it in miniature before beginning or completing construction of the actual ship. During and after the Napoleonic Wars, prisoners of war were permitted to make ship models from bones and other materials to sell in order to purchase food and other necessities. More recently, very small models of ships have been used by military strategists as part of naval wargaming or instruction in ship recognition.

Votive ship Riksnyckeln (1630) in Gärdslösa Church, Borgholm, Öland, Sweden (photo Rottabaga)

Note there is an inscript of 1691 on the model of the Riksnyckeln and it commemorates a battle between the Danish and Swedish navies in the Kalmar Strait in 1679.

For those familiar with the sea and with the Scriptures, the words of Psalm 107:24–30 are a literary reminder of the nautical experiences that were the genesis of many of these ships of prayer and promise:

They that go down to the sea in ships, that do business in great waters;

These see the works of the Lord, and his wonders in the deep.

For he commandeth, and raiseth the stormy wind, which lifteth up the waves thereof.

They mount up to the heaven, they go down again to the depths: their soul is melted because of trouble.

They reel to and fro, and stagger like a drunken man, and are at their wit’s end.

Then they cry unto the Lord in their trouble, and he bringeth them out of their distresses.

He maketh the storm a calm, so that the waves thereof are still.

Then are they glad because they be quiet; so he bringeth them unto their desired haven.

(KJV)

Votive ships remain as a reminder to the curious and the faithful of the long and intertwined history of religion and the maritime world. For those who know and love the oceans, there are wonders in the deep and great respect for the sea, the sailor, and the wind that blows.

Further Reading

Davidson, H. R. E. “Church Ships and Ship-Festivals.” Folklore 64:3 (Sept., 1953): 433-36.

Freeston, Ewart C. Prisoner of War Ship Models 1775–1825. London, Conway Maritime Press, 1987.

Harley, Basil. Church Ships: A Handbook of Votive and Commemorative Models. Norwich, UK: The Canterbury Press Norwich, 1994.

Lavery, Brian & Stephens, Simon. Ship Models, Their Purpose and Development from 1650 to the Present. London: Philip Wilson Publishers, 1995.

Streuding, Jaclyn Haley. “Success at Sea: Maritime Votive Offerings and Naval Dedications in Antiquity.” Unpublished M.A. thesis, Texas A&M University, 2014.

Wegner, Dana M. “Ship Models,” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Maritime History, John B. Hattendorf, ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007, Vol. 3: 204-206.

Wester, William C. “The ‘Beulah’–Restored, Rededicated.” Journal of Presbyterian History 62:4 (Winter 1984): 283-90.

Westerdahl, Christer. “Medieval Carved Ship Images Found in Nordic Churches: the poor man’s votive ships?” International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 42:2 (September 2013): 337-47.

Timothy J. Demy is a professor at the U.S. Naval War College (Newport, RI) and retired Navy chaplain. He is a graduate of the University of Cambridge with a master’s degree in international relations. Elsewhere, he earned doctorates in historical theology and also in the combined fields of technology and the humanities. The author and editor of numerous books and articles, he is an avid bibliophile, classical music lover, and student of piano.