By Hilary Letwin –

Sitting for one’s portrait is not the first thing one might expect to do in self-isolation during a global pandemic. But, that is precisely where I found myself on a recent gray Tuesday morning, posed on my balcony in Vancouver at 9 am, my morning coffee steaming beside me, the traffic noise from a nearby road punctuating my conversation with the artist, Harry Hancock.

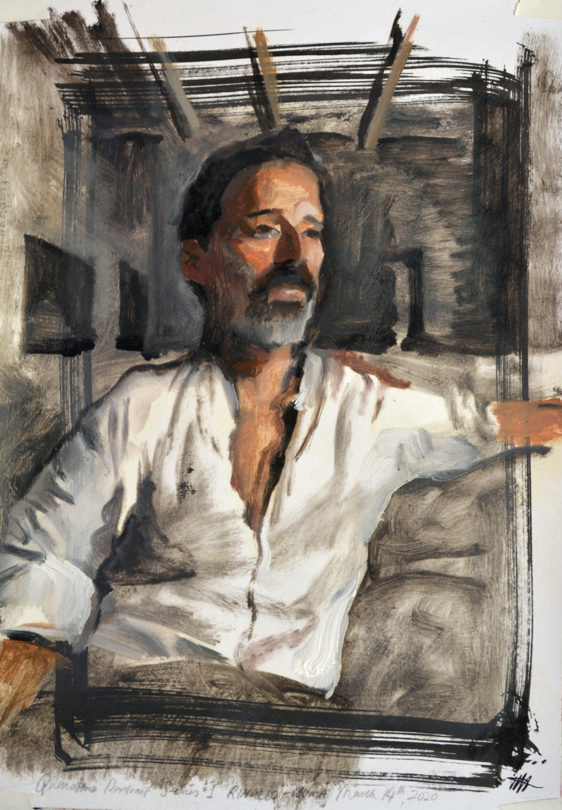

I met Hancock over a decade ago, while living in London. He trained in the materials and processes of Baroque portraiture and holds a degree in Renaissance art history from the Courtauld Institute of Art. He now works as a professional portrait painter, typically taking commissions, working in a traditional technique called “sight-size”, painting at 1:1 scale, informed significantly by historical painting. Hancock has worked previously as a Latin teacher and has a self-professed life-long passion for antiquity, specifically, and history in general.

“Painting likenesses of loved ones is a way of preserving their memories. This is why the idea of posthumous portraiture – or those of any absentee loved ones – appeals to me so much. There are eternal, foundational human needs being met through the technology of painted portraiture, which in my case extends to include videoconferencing. And it’s an act of love, to paint someone’s portrait.”

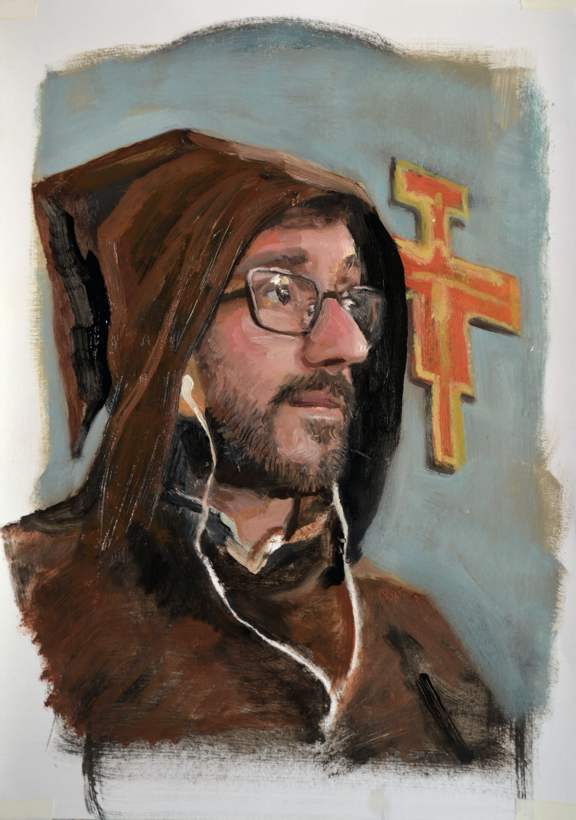

My picture is number 33 of 40 in a series of Quarantine portraits; the total number decided by the numerical source for the word “quarantine” or quaranta giorni, forty days in Italian. During this period, Hancock meets with his sitters on Zoom and spends a little over an hour creating remarkable oil sketches.

So far, he has painted people who are living in India, Spain, France, Greece, the USA, Italy and the UK: drawing poetic connections around a world that has been physically stilled.

“I wanted to focus on a project that would allow me to keep painting, giving me a fluidity that only comes from daily artmaking.”

Hancock, who currently lives in Barcelona, has been under a severe lockdown at home with his partner, for over 7 weeks at the time of writing, only able to go outside for essential groceries and the pharmacy. When Hancock first started these portraits, he saw it as an opportunity to reconnect with old friends.

It is an immensely relaxing experience to sit for a painted portrait, especially with an artist as genial as Hancock. So many of his sitters have ended the experience with gratitude for the opportunity to switch off, if only for a little bit. Our conversation switched fluidly between pandemic topics and those related to our “normal” lives: work, partners, families, and hobbies.

He has developed a technical set-up that enables him to work in this way. Hancock has his desktop with the view of his sitter, opened next to a livefeed showing his painting in progress. He admits that it took him a few portraits to work out this arrangement. As he nears the end of his series, he is running out of supplies and has yet to source some essentials. He is out of turpentine and has been using mineral oil instead. He is painting the portraits on an old sketchbook of heavy paper, over which he had, long ago and accidentally, spilled some India ink. Each page has a roughed-out abstract face, akin to those by Picasso, which he uses as a departure point for this series.

I watched in wonder as he transformed this older sketch into a likeness of me in so little time. Realistic portrait painting is an alchemy: making something out of nothing. Hancock’s portraits mirror our current days that are doubly charged with poignancy and vibrancy. These portraits are a souvenir of these bizarre, near absurd, times and a tangible reminder of why humankind has long prized portraiture. Collective and personal memory shapes us. May our memories of this time be not only about loss and insecurity, but also about how the arts offered comfort and crystalized us to our fundamental selves.

***

Hancock is presenting an Instagram Live talk about his Quarantine Portraits on Thursday, May 7 at 7 p.m. in Barcelona (Barcelona time). Join in @harryhancockart.

***

Hilary Letwin holds a PhD from The Johns Hopkins University in Art History. Her recent publications include Saints, Sinners and Souvenirs: Italian Masterworks on Paper and Talk of the Town: Molly Lamb Boback. She works as Assistant Curator at the West Vancouver Art Museum, Canada.