By Andrea M. Gáldy –

Prepare to get lost in ancient Egypt. Actually, prepare to get lost constantly for this is a museum cleverly hidden within the Munich Kunstareal (Fig. 2). As you approach the Museum of Egyptian Art you turn from a normal visitor into an archaeologist discovering a new royal tomb. The entrance looks much like a combination of an actual tomb somehow merged with an Egyptian Pylon gateway. Ramps lead you down into the lobby, more ramps conduct you into the museum space proper, and a bright metal strip inserted in the floor conducts you from one thematic section to the next.

Last summer Munich’s collection of Egyptian art finally moved to a brand-new, modern state-of-the-art museum. Brought together from three previous locations, the collection pieces no longer compete with the early-modern architecture, for example at the Residenz, but are enhanced by the time-less setting of their new home. Even the fashionable twilight interrupted by spotlights so beloved by designers creating museum interiors makes sense here (Fig. 3). It still gives me migraines, but it also draws the visitors’ attention to the objects which well deserve to be studied in some detail.

The visitor is supported in this endeavour less by information written on cards than by the presentations on touch-screen table tops and on audiovisual tablets (included in the museum ticket of €7, reduced €5, Tue to Sat, €1 + €1 on Sun; children under 16 go free but have to pay €1 for the mobile guide). The idea is not to detract from the impact of the exhibition pieces, which is all very well if you can be sure that every visitor is either a specialist in Egyptian art or is mainly interested in the aesthetic powers of Egyptian sculpture. I would think that most people know a bit about Egyptian art, some may have been to Egypt or have seen Antonius and Cleopatra at the theatre. Nonetheless, in my view at least, the information provided is too scarce and the tablets are helpful only to some extent: they do not cover every piece in the exhibition and where they give explanations, tempt one to look at the screen rather than at the objects. So far, they are only available as German-language guides but the courteous and well-informed staff confirmed that an English-language version is planned. The cards and touch-screen table tops are in both German and English. It astonishes though that in a place where quite obviously a lot of time, money and effort have been invested, most texts would have benefited from more careful proof-reading and that the English translations might have been less awkward. No doubt, the management and curators will soon sort out such minor flaws. And, the new media are used less obtrusively than in other museums, while offering a chance to see reconstructions of damaged pieces or give visual context.

What I appreciated most, however, was the broad range of topics discussed by and in the exhibition: Egyptian culture and artefacts consist of so much more than mummies, pyramids and pharaohs. It is true that death and the afterlife played an important role (Fig. 4) and that the Egyptian deities came in a bewildering variety of shapes. Nonetheless, this was a culture of amazing longevity which exerted considerable influence on later civilisations and religions such as that of Classical Antiquity in Greece and Rome as well as on Late Christian Antiquity. The figure of mother and child (Fig. 5), whether Isis or Madonna, can thus be shown to have been an object of veneration from Egyptian to our own times. Symbols such as the cross have also been adopted by diverse religions and cultures. Within the five millennia during which Ancient Egypt existed, art underwent many different phases and while some elements stayed the same throughout, certain stylistic details changed sometimes with the advent of a change in religion (Fig. 6), as in the Amarna period female statuette, and sometimes as the result of an encounter with people arriving from neighbouring countries or further afield.

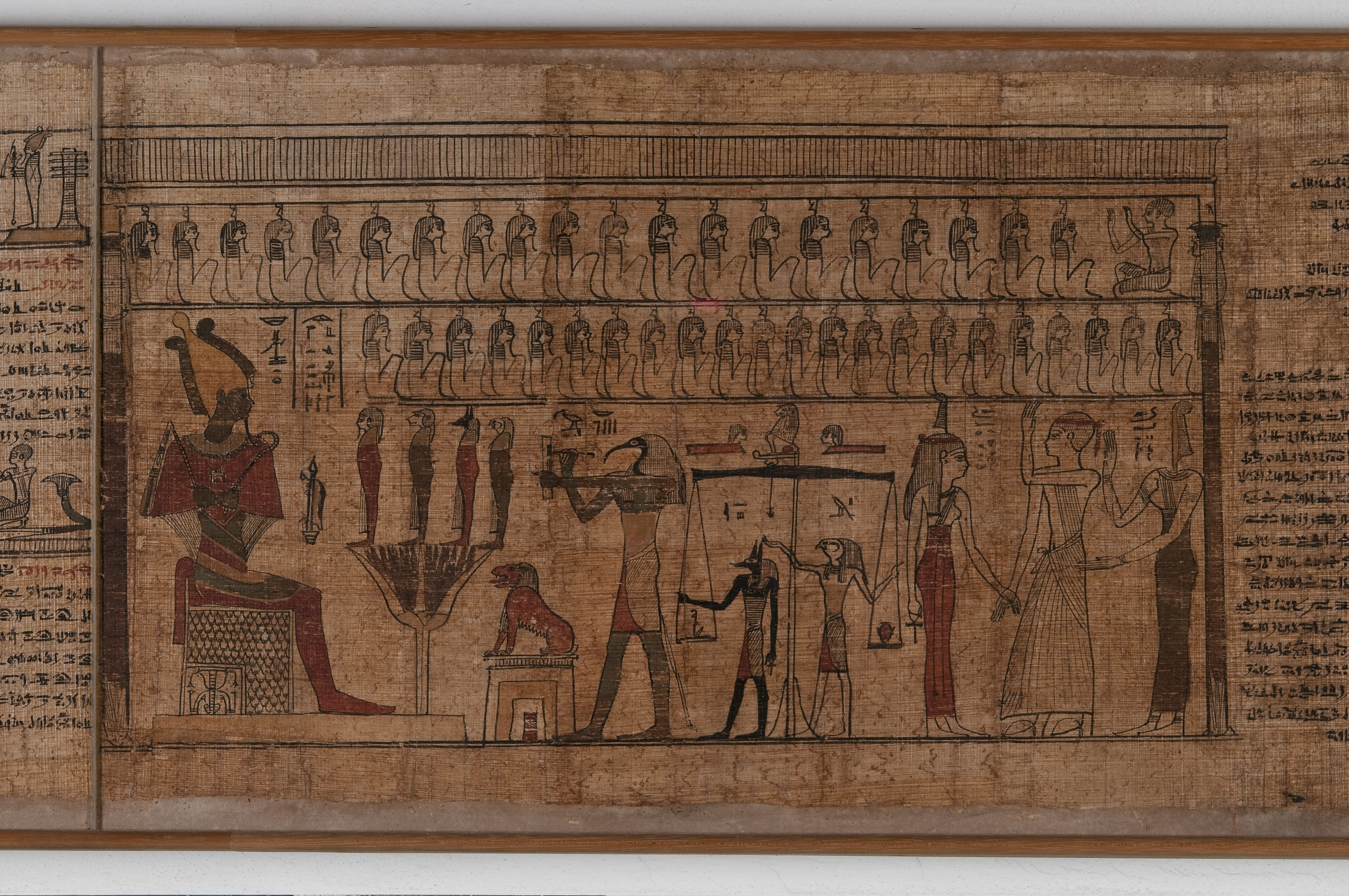

There is also a salutary reminder that our ancient Egyptian brothers and sisters were not so different from ourselves. The distance along the trajectories of Deep Time and Deep Space may have created mists of mystery. But these can be cleared away the moment one shifts one’s attention from the Book of the Dead (Fig. 7) – legible through the help of a translator screen – to investigate Egyptian achievements relating to the applied arts (Fig. 8) or the importance of the written word for record keeping and administration. No wonder, the deciphering of the hieroglyphics was such a breakthrough for it opened up the thoughts, dreams and fears of people living within a highly organised society. Note in this papyrus “Hall of Two Truths” (chapter or Spell 125) scene, from left to right the god Osiris, monster Ammit “gobbler of souls”, god Thoth, a small god Anubis at the scale with small god Horus (or Harakte-Ra), and the goddess Maat followed by the deceased.

In my view the strongest point of the museum is indeed the presentation of Egyptian art as far from homogenous but rather well-connected as part of the geographical neighbourhood. Objects from Nubia and the Sudan as well as from Assyria provide artistic and political context; they also attest to a lively exchange between cultures with influences travelling both ways. When Egypt ended up with a Greek ruling family (Ptolemies) as a result of Alexander’s conquests, the ensuing Egyptian-Hellenistic culture was successfully passed on to the succeeding Roman conquerors who absorbed the cults along with the material culture. Egyptian pieces have been found in Pompeii as well as in Rome and attest to a long-standing fascination with the kingdom and later province on the Nile. When Emperor Hadrian’s favourite Antinous (Fig. 9) drowned during a visit to Egypt in AD130, his imperial host dotted the Empire with statues of his beloved. The museum shows an Egyptian version of Divine Antinous, which probably was once part of the display of Villa Adriana at Tivoli.

This statue shows the well-known, idealised and identically reproduced portrait of the young Greek man in combination with the conventions of Egyptian dress. But long before the 2nd century AD Egyptian portraitists were well able to present facial traits, age and posture in their sitters. A copper statuette of a Vezir (Fig. 10) as well as the small portrait head of Sesostris III (Fig. 1) , also spelled Senoswret III, indicate the artists’ powers of close observation as well as of the faithful rendition of specific characteristics at least from the Middle Empire (12th Dynasty) onwards. For all its undoubted continuity, Egyptian art was constantly undergoing change and development. Even though this did not always happen as radically as during the Amarna period (Fig. 6), some of the works of art are so individualistic that they approach caricature, as in Vezir below.

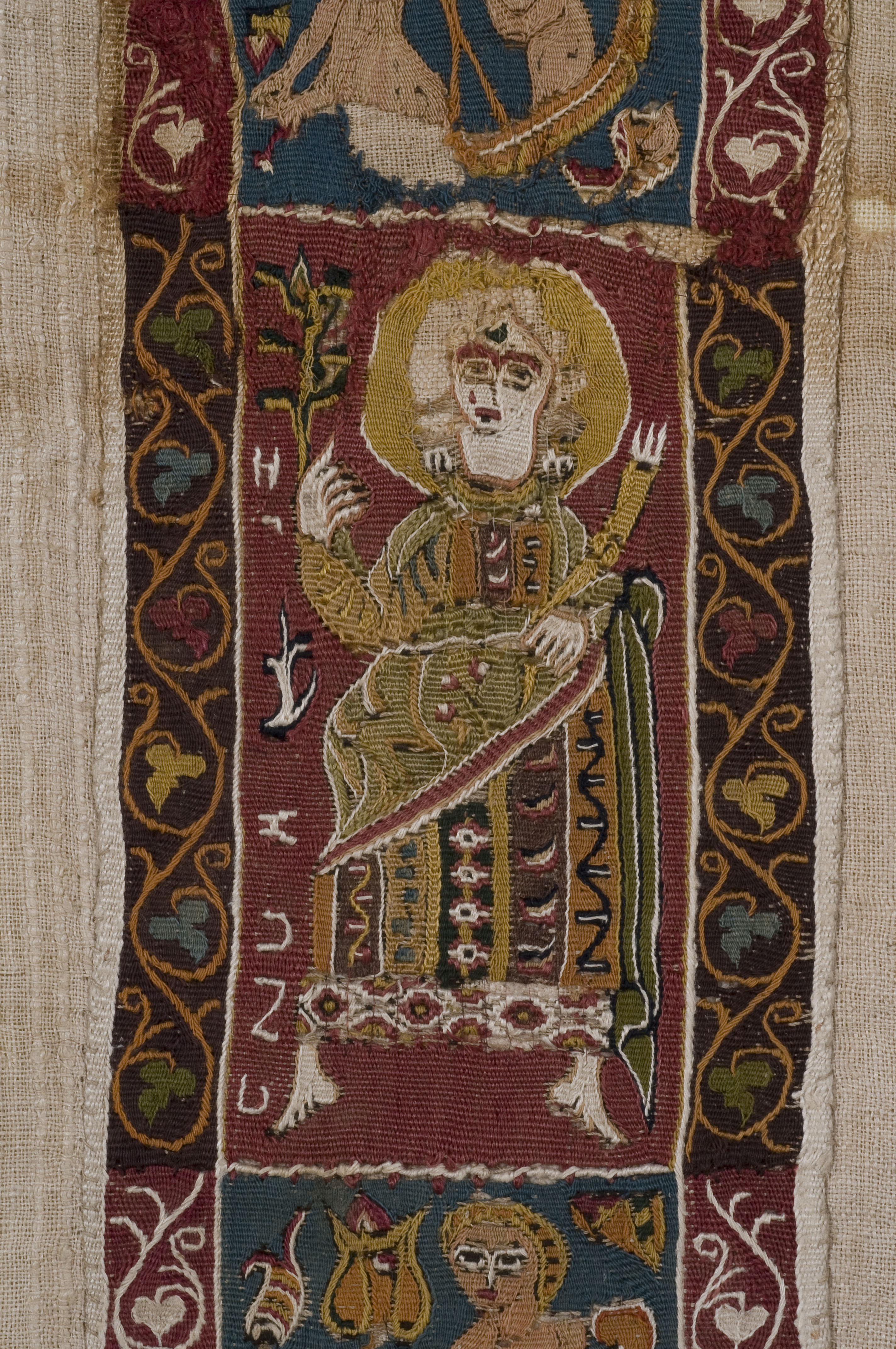

It is particularly interesting that the museum display does not take the transition from pagan Antiquity to Christian Antiquity as its cut off point but rather continues deeply into Coptic Egypt. The Pharaohs are gone, Greece and Rome are distant if important historical models, but communities of Coptic Christians do still exist. The Coptic tunic (Fig. 11) of the 5th/6th century AD is thus able to act as a cultural and religious bridge today as much as it did at the time of its creation when the artist combined traditional Mediterranean visual language with the symbols and narratives of a new religion.

Altogether this museum is a great addition to the Munich museums and if you visit you will enjoy exploring its Egyptian legacy. I will certainly go back for more.

http://www.aegyptisches-museum-muenchen.de/

Staatliches Museum Ägyptischer Kunst München, Arcisstraße 16 , 80333 München

If not otherwise stated, the copyrighted photos are from © Staatliches Museum Ägyptischer Kunst

Photographer: Marianne Franke