By Sylvia Rhyne and Eric Redlinger

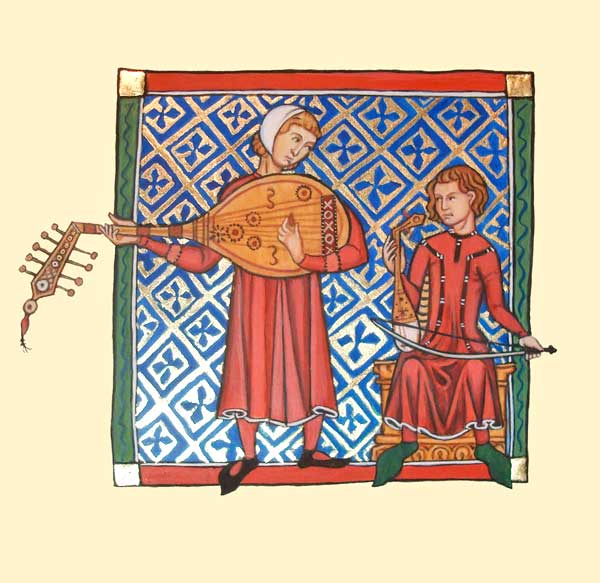

Editor’s Note: Sylvia Rhyne, Soprano, and Eric Redlinger, Tenor and Lutenist, are the musical group Asteria (Late Medieval Vocal and Instrumentalists) who share a Courtly Love story in following their passion and dream in Burgundy. Learn more about them and their music on their website: www.asteriamusica.com. They perform at Stanford University (free admission) Friday, Nov. 18, at Campbell Recital Hall, Braun Music Center, 8 pm. “Asteria – in Search of the Lost Song”

Editor’s Note: Sylvia Rhyne, Soprano, and Eric Redlinger, Tenor and Lutenist, are the musical group Asteria (Late Medieval Vocal and Instrumentalists) who share a Courtly Love story in following their passion and dream in Burgundy. Learn more about them and their music on their website: www.asteriamusica.com. They perform at Stanford University (free admission) Friday, Nov. 18, at Campbell Recital Hall, Braun Music Center, 8 pm. “Asteria – in Search of the Lost Song”

Emerging into the soaring, flamboyant gothic courtyard of the 15th century Hotel Chambellan in the heart of medieval Dijon feels truly like teleporting to another time and place. The effect is only heightened by the fact that to get there you need to duck through a narrow, dark passageway that departs from a non-descript, inconspicuous doorway opening onto the facing rue des Forges. The almost overwhelming sense of transition is not just an aesthetic one, although the setting, with its gothic spires, impossibly intricate lacy, filigree banisters and leering gargoyles, certainly plays a role. One realizes immediately that something more subtle and powerful is at play here, something that touches an emotional chord. In the Chambellan, everything feels right: the light, the air, the hand-cut stones that each bears a small mason’s mark, proof of its artisanal provenance. The magic works because the context feels complete. It is to a large extent this missing contextual framework that often leads us to find many historical works of art naive, lackluster or, in the case of performances of medieval music, simply boring.

When we first met, we were coming from very different musical backgrounds: Sylvia from the world of musical theater on Broadway, and Eric from the world of electronic music, where he spent time as an intern in the studio of composer Philip Glass. But we both had a deep love of renaissance music and had studied it at college. One day, Eric pulled out a stack of Burgundian chansons from the 15th century that he had gathered while at the Schola Cantorum in Basel, Switzerland. It was this repertoire that sparked our collaboration, one that has continued for the last ten years. As we explored these passionate love songs, we began to ask ourselves questions about the people who wrote them. Who were they? Where did they live? What were their lives like? What, in other words, inspired these remarkable, sometimes inscrutable lyrics? We were convinced that courtly life and behavior in the 14th and 15th centuries must have been anything but boring!

In fact, compared to today, the late Middle Ages appears to have been a time of exaggerated expression of the human condition. Lords, courtiers, pages — everyone rejoiced, wept and despaired with great frequency and passion. The chivalric tradition, first codified nearly four hundred years prior by the troubadours just after the turn of the first millennium, still held sway at the dawn of the renaissance. Life, for the nobility at least, involved an elaborate ritualization of virtually every aspect of public life. It is this context of emotionally charged expression that led to a blossoming of Burgundian poetry, and its musical vessel, the polyphonic chanson, its verses overflowing with praise to the Lady and promises of devotion to love’s decrees. But what did it all mean? And how were we ever going to get to the bottom of these questions from the reading room at the New York Public Library?

In 2006, we took the plunge and rented a small house for six months in the countryside outside of Carcassonne, in the Languedoc region in the south of France. The area near Carcassonne is decidedly not that “south of France”. There are no beaches, glamorous film festivals or endless fields of lavender here, rather a mostly parched landscape of craggy hills, rude valleys, and a predilection for fierce, days-long wind storms pushing chilly, dry air down from the north. But this is where the troubadours lived so long ago and in order to get to the bottom of the origins of “courtly love”, we were going to have get to know this place.

Standing upon the ramparts of storied castles such as Lastours and Puivert from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, we discovered that even today we were seeing a barren landscape such as the troubadours would have seen. The emptiness and isolation speak directly to the yearning one feels in the poetry they wrote – the longing for things far away and unreachable. As we explored those rugged landscapes, we began to understand themes in their lyrics that had seemed either mysterious or simply banal when viewed from the context of today.

It was a continuous surprise to us to discover that many of the elements of Western fairy-tales, so often associated with medieval life – such as the princess in a distant tower, or the youngest of three princes who must leave to find his fortune in a far off land–far from being debunked, in fact could often be directly traced to actual medieval customs or rituals. We discovered that it was indeed the youngest princes who really did leave their homes to seek their fortunes, although not necessarily for fairy-tale reasons: being the last in the succession ladder, their only hope for wealth and power was to marry into a different family clan. Thus were born some of the actual roots of the numerous “knight errant” stories that pepper Arthurian and other fantasy lore. Since most of the geographically closer landowning noble families were already effectively inbred through waves of power consolidation over the centuries, that “youngest prince” had often to go quite far afield to find new and suitable territory, sometimes even to other countries.

For us, this prince narrative highlighted a phenomenon that we encountered over and over again as we explored the roots of courtly love; stories and legends that seem at first to be merely concocted entirely from someone’s imagination, in reality often have historical precedents or were inspired in some way by real events. Realizing this helped us to resist the urge to discard certain poetic themes as banal or unremarkable because even themes that seem straight forward take on new shades of meaning when properly contextualized.

It was months later, after we had left the south for the decidedly more fertile territory of Burgundy that a different courtly motif began to reveal a part of its mysterious origins. Medieval verse is riddled with mentions of slander. The authors of the epic Roman de la Rose, one of the towering monuments of medieval literature, saw fit to create a major antagonist in the form of an allegorical figure named “wicked tongue” (malbouche) who continually thwarts the romantic intentions of the story’s hero. Characters such as “wicked tongue”, or one of his many equally gossipy variants, abound in the literature and songs of the time – why is this? Part of the answer is pragmatic: medieval culture was a profoundly hierarchal one. Wealth was almost entirely held and exploited by the noble elite, and only small amounts trickled down through the ranks of functionaries to the general population. Implied in such a social structure, however, is a responsibility of the lord for the general wellbeing of the people in their service, and this responsibility extends much further than such relationships today. In addition to food, nobles were generally required to clothe their attendants. Since the appearance of their servants was a reflection on themselves, large sums were dispensed regularly for clothing and again on special occasions for special outfits. During the reign of the Valois dukes in the 15th century, travel and related expenses were similarly paid entirely out of ducal coffers. All this dependence created a scenario in which you quite literally owed the duke your life and the threat of losing all this privilege must have seemed daunting indeed. Taken together with the medieval obsession with honor and protecting one’s good name, the very real threat of malicious slander throwing someone’s reputation in doubt must have been taken extremely seriously.

But there is another, more personal, piece of the puzzle that we observed during our stay that shed even more light on the mysterious prevalence of slander as a theme in the late medieval poetry. In 2007, we were invited to be in residence for two weeks in the only remaining palace belonging to the dukes of Burgundy in Burgundy. The Chateau de Germolles, today a private residence, was built by Philip the Bold at the end of the 14th century for his wife, Marguerite of Flanders. Philip, the first Valois duke of Burgundy and a brother of the king of France, spared no expense in renovating this residence for his duchess, and some of the best artisans of the age, including the sculptor Claus Sluter, and the painter Jean de Beaumetz, were engaged to decorate it. As with Dijon’s Hotel Chambellan courtyard, one feels at Germolles a palpable connection with history, particularly when standing in the duchess’ garderobe, a superbly preserved medieval chambre that is covered entirely from floor to ceiling in its original 14th century painted murals.

Documents chronicling the movements of the nobility in the late Middle Ages reveals that many courts were itinerant, moving from castle to castle to consolidate political and social power. The more land you owned, however, the more territory you had to cover regularly to insure fealty and loyalty from your subjects. Thus, the Duke of Burgundy would move with his entire retinue between his various castles, including about three hundred people comprising courtiers and other personnel, as well as dozens of wagons to carry his furniture and other possessions.

At first glance, life at court in a Burgundian palace appears to have been a gracious affair, with large rooms, each sporting large fireplaces. Even the duchess’ private ‘high chapel’ had its own fireplace. Rooms on the third floor are even more opulent, with loft-style rooms spanning the width of the castle. Large, medieval poster beds (a replica of which exists today in one of the upstairs rooms at Germolles) evoke luxurious spaciousness. That is, until one learns that these rooms were often shared by up to twenty people at a time, and beds commonly slept an astonishing eight to ten people each; those three hundred people had to live somewhere! Even the large “private” rooms of the princes served multiple functions by necessity; the duke routinely ate, relaxed, slept and held court in the same room, with furniture moved or repurposed as needed. With this contextual backdrop, life at court probably contained much less polite banter and a great deal more gossip that one initially imagines. In fact, the image it most conjures up for us today is one of a sort of perpetual high-school: certainly a fertile petri dish for slanderous gossip!

That year we also “discovered” an important 15th century manuscript in the municipal library of Dijon, which is fittingly located in an old Jesuit monastery – fittingly because monasteries were among the first places where books were manufactured (initially by hand, of course) and collected. We didn’t actually discover this manuscript in the literal sense; historians have known of its existence for years. It has never, however, been edited or transcribed. In other words, it hasn’t been translated into modern musical notation. This means that the manuscript and its contents were essentially unknown to musicians, even to many who specialize in early music. Over the course of the past four years, we’ve been returning to Dijon in the summer months to work with this manuscript, with the goal not only of performing and recording this wonderful, forgotten repertoire, but also to make our personal performance editions available to other musicians and enthusiasts. Along the way, we have made numerous friends in and around Dijon, and have become particularly fond of the Burgundian tradition of repaying offerings of music with offerings of wine, particularly when the place where this exchange is taking place happens to be called Volnay, Gevrey Chambertin or St Romain.

When medieval music and poetry is presented in a vacuum, that is without a sense of where it came from and for whom and by whom it was written, it is a bit like drinking one of the aforementioned vintages while holding your nose and with your eyes closed: you only get a small part of the experience. There is something tantalizing, but ultimately out of reach. To remain with wine for a moment, learning about the ‘terroir’ and amusing details like the Burgundians’ habit of aerating the wine in their mouth by slurping the first few sips makes the whole experience of drinking wine from Burgundy more pleasurable and, ultimately, more meaningful. In our experience the same thing happens with music. Just as you don’t have to be in Burgundy to appreciate a great wine, you don’t have to have visited a ducal palace to appreciate the beautiful music of that era (although it certainly doesn’t hurt), but to the extent that you (or the performers) are able to integrate some of the contextual underpinnings, the moment has the potential to transcend the aesthetic domain and become an emotional one.