By Andrea M. Gáldy –

Southern Germany offers more than skiing holidays and the Oktoberfest, nice though they are. Traces of ancient Celtic and Roman settlements in the former Province of Raetia can still be admired, while during the mediaeval and early modern period the imperial free cities, bishoprics and monastic foundations acted as seats of learning and industry. This is the second part of a mini-series dedicated to “hidden gems” in Bavaria: while Part I looked at two Roman Foundations and their early modern afterlife, Part II discusses a number of small museums, which may be far from the bright lights of Munich but are no less interesting than the attractions of the Landeshauptstadt.

The pre-Alpine area of the Allgäu offers a wealth of diverse cultural sites. An important theme in the museums is the close connection between art and nature, a view that was not unusual until the eighteenth century. During the European Enlightenment with its growing focus on the natural sciences, these ties started to unravel. Events, such as the first balloon flight or the Venus transit of 1761, attracted large crowds of spectators; the latter also prompted the discovery of a new continent in the Southern Hemisphere.

One of the most recent additions to the museum landscape is the Südseesammlung (for more information and images visit http://www.suedseesammlung.de/index.php?plink=index) at the market town of Obergünzburg, which attests to the attraction far-away places have long held for the population of land-locked Swabia. About 100 years ago, Captain Karl Nauer sailed for Deutsche Lloyd to the Bismark Islands in the Southsea. The fascination with such distant worlds caused him to spend much time and effort to build a considerable collection of naturalia and ethnographica. In 2009, Obergünzburg thanked him for the bequest of these objects with a purpose-built museum dedicated to his memory. The Südseesammlung offers surprising insights in the history of an encounter between cultures staged in a state-of-the-art display and presented by an enthusiastic and knowledgeable team under the direction of Ulrich Habich.

Nearby Memmingen – a free city of the empire, which played an important role during the peasant wars of 1525 –was the location of the workshops run by the Strigel family during the fifteenth and sixteenth century. The Strigel museum under the direction of Axel Lapp, Ph.D. (http://www.memmingen.de/strigel-museum.html) is set up in a former hospital of the order of St. Anthony, which operated at Memmingen from the thirteenth century to c. 1562. The monks had found a treatment for patients infected with St. Anthony’s fire, a disease caused by the ergot fungus in grain. The display in the section dedicated to the order’s monastic history attests to this important chapter in medical history (http://www.memmingen.de/antoniter-museum.html).

Memmingen turned Protestant early during the Reformation, while the surrounding countryside stayed Catholic. Workmen active in Memmingen (for example Thomas Heidelberger and Josef Kels) were hired to create elaborate pieces of furniture for the Abbey of Ottobeuren and probably gained much righteous satisfaction from leaving the portraits of Luther and his wife in the form of beautifully made intarsiae on the finished product (in the Sacristy and not on public display).

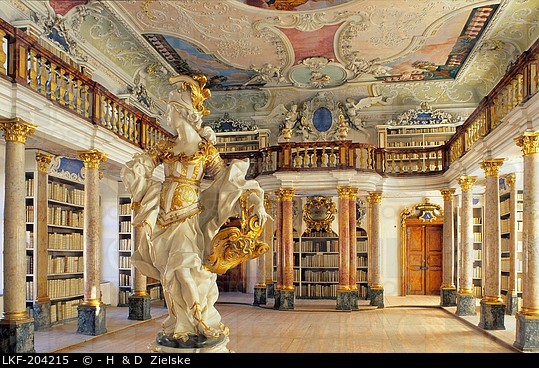

In the eighteenth century, monastic foundations of Southern Germany, such as the Abbey of Ottobeuren, were hubs of learning, which hosted vast libraries (see above Library photo) and rich collections of works of art as well as of naturalia. The monks taught day students at the monasteries while also lecturing to university students at Salzburg or Ingolstadt. Indeed, monks engaged in research on diverse disciplines of the emerging natural sciences and developed new school curricula in an attempt to include mathematics, physics and the life sciences in their teaching. By the mid-eighteenth century, the leading role of the clergy among the natural scientists of the era was acknowledged by the inclusion of a number of Benedictines among the founding members of the newly established Bavarian Academy of Sciences (1759). Monastic scholars often collected naturalia, such as birds and plants, displayed in special cabinets. Few of these cabinets survived the secularisation of 1803. Many of the books, works of art and preparations of fauna and flora were taken to Ingolstadt and found a new use as part of university collections.

Nevertheless, the Abbey of Ottobeuren – famous for its Baroque Basilica and internationally renowned concerts – hosts a museum founded in 1881 but actually going back to the collections of Abbot Rupert (1724) and, thus, to the period when the present church and monastery were constructed. The monastic foundation itself is even older and celebrated its 1250th anniversary in 2014. The museum’s modern exhibition was originally created by P. Egidius Kolb in 1984 and is, after the monastic museum at Kaufbeuren, the oldest such display still in existence. For the past two years, Brother Tobias has been in charge of the museum. He started with a major construction overhaul of the premises, while also working on a new exhibition concept. For this endeavor, outside expertise has been sought but Brother Tobias plans to include in the final museum narrative a strong focus on Benedictine life over the centuries. The new concept emphasizes the role of religion and faith as necessary context for the creation of the works of art displayed at the museum.

Unfortunately, many of the objects once owned by the Abbey are no longer at Ottobeuren: many objects were confiscated after 1803; other collectibles such as shells were sold after WWII or given to specialised museums. The collection of stuffed birds was taken to the Abbey of St. Stephen at Augsburg in the 1980s, while many of the scientifica are now at the Bayerisches Landesamt für Vermessung und Digitalisierung (Munich). A terrestrial and a celestial globe as well as a telescope are, however, still at Ottobeuren and the recent construction work has led to the discovery and restoration of the ceiling decorations in the erstwhile cabinets of mathematical and scientific instruments.

What makes the museum so important is that, despite numerous losses over the centuries, it is still a display of at least part of the original collections within the original premises. These consist of two interconnected parts, the former staterooms of the prince abbot and the art gallery. The paintings and sculptures, including fine examples of late-Gothic altar panels as well as Renaissance and Baroque art, were already part of the Baroque collections and displayed in these very rooms, even though one cannot be sure about the original picture hang. Transported to Munich from 1803, the works of art were held in a deposit, some were sold off, others returned to Ottobeuren for the Abbey’s 1200th anniversary in 1964 as a loan from the Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlung who is the current owner. Apart from the late-Gothic works mentioned before, the Abbey also acquired more modern works of the Renaissance and Baroque period, on display in a dedicated room. Abbot Kindelmann attempted to introduce Renaissance style works of art, for example, the so-called Kindelmann altar (1535-40) and lime wood reliefs by the so-called “Ottobeurer Meister” created during the first half of the 16th C (known for the typical “Parallelfaltenstil” attr. to Hans Thoman, active in Memmingen 1514-1525 – also see limewood relief at left).

While the necessary building work in the museum and princely apartment was completed in 2014, the future will bring a thorough re-conceptualisation of the display. An educational outreach programme will engage the interest of a young audience, while multimedia displays aim to take full advantage of current technical possibilities. Nevertheless, until these projects can be completed, the Klostermuseum is well worth a visit: art, nature, architecture, scholarship and monastic spirituality combine to an intriguing mixture as attractive for today’s beholders as they were in the eighteenth century. For more information about the Abbey of Ottobeuren, visit http://abtei-ottobeuren.de/pages/home/museum.php. The Abbey of Ottobeuren is well worth a visit all year long and offers a rich programme of concerts, conferences and educational seminars. The region of Unterallgäu invites scholars and tourists to discover architectural and historical gems as well as the beauties of its landscape off the beaten tracks.