By Laura Rehwalt –

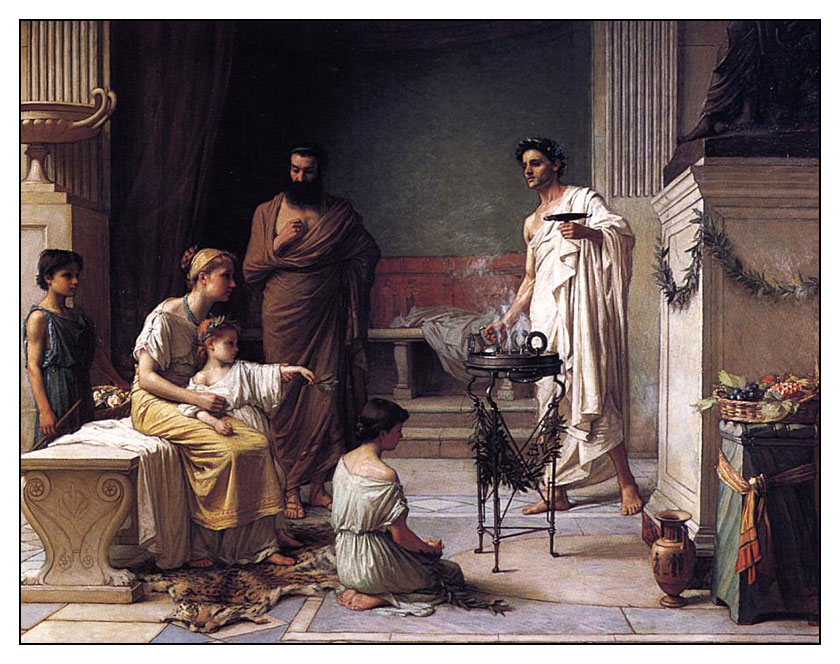

How old is the idea of psychiatry and how long has psychotherapy been practiced? Most likely the Greeks and Romans had an inkling, even if these two words are fairly modern. And given that Plato and Galen had a few things to say as well, it should not surprise us that doctors have known for thousands of years that mind and body are connected. “Soul Healing”for the Ancient Greeks – practicing psychotherapy or psychiatry – was not only relevant but also studied in seminal ways by the medical profession, just as it continues to be studied today. We may often refer to anything related to the study of the mind as modern psychology, but the ancient Greeks and Romans saw psychology, medicine and philosophy in a more integrated way since the idea of mens sana in corpore sano or “healthy mind in a healthy body” as a latin paraphrase of the ca 600 BCE Greek sage Thales. Body and mind together was an important principle linking both parts of our human experience, the internal and the external. Perhaps one place to look for this soul healing would be in the Asklepeian tradition where healing sanctuaries not only addressed the body but the soul, especially at Epidauros where patients laid down in a special room and slept and afterward related their dreams to the doctors-cum-priests. [1]

Some forms of mental health therapy and psychological diagnoses can be traced back to antiquity. The Greeks and Romans were among the first to recognize mental illness as a medical condition that also influenced physical health. At times, of course, they may also have had some bizarre ways of treating certain conditions. For example, many believed that hysteria (from hyster or “womb” in Greek) was a condition for which only women were treated, or that depression could be treated by bathing – although this may not be so strange – or that psychosis was treatable by “blood letting” of n excess of black bile ( hence melancholia). However, at the same time, many ancient cultures had a sensible realization that positive words and hope had value in healing the soul – even the biblical Proverbs 17:22 said, “A merry heart does good like medicine, but a crushed spirit dries the bones” or Proverbs 15:1 “A soft answer turns away wrath but a grievous answer stirs up anger.” On the other hand, where superstition and ignorance prevailed, proper medical treatment was limited by false diagnosis and false or even harmful practices.

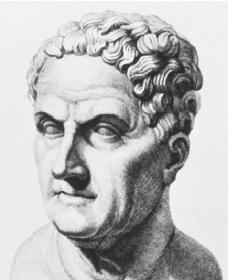

But the Ancient Greeks partly led the way in scientific study of psychology and understanding of some psychosomatic conditions like depression or loss of desire. In fact, Aristotle can be given credit for formulating the foundations of psychology. Because Greek philosophers studied how human personality and character were expressed as either part of rational, deductive processes or as impaired irrational processes, it should not be surprising that Aristotle mixed psychology with a philosophy of the mind and thus his empirical approach was a forerunner of modern psychological approach.

In early anticipation of Freud, one of the most interesting critical approaches and therapies the ancient Greeks used to understand individual human anxiety was dream interpretation. The Greek thinker Artemidorus (2nd c. CE) wrote Oneirocritica, the first Greek book of dream interpretation after he traveled and collected people’s recollection of dreams and whether what could be called their outcomes matched their dreams by some form of logic. He divided dreams into at least two basic types:

“Some dreams, moreover, are theorematic (direct), while others are allegorical (figurative). Theorematic dreams are those which correspond exactly to their own dream-vision. For example, a man who was at sea dreamt that he suffered shipwreck, and it actually came true in the way that it had been presented in sleep. For when sleep left him, the ship sank and was lost, and the man, along with a few others, narrowly escaped drowning…Allegorical dreams, on the other hand, are those which signify one thing by means of another; that is, through them, the soul is conveying something obscurely by physical means.” [2]

Artemidorus also tried to understand both the personal immediate circumstances and overall context of the dreamer as a holistic approach, believing that the least possible item could greatly influence the dream and how to understand its meaning. This anticipates modern diagnosis as well and is also part of the scientific method of isolating variables in an experiment.

“It is profitable – indeed, not only profitable but necessary – for the dreamer as well as the person who is interpreting that the dream interpreter know the dreamer’s identity, occupation, birth, financial status, state of health, and age. Also, the nature of the dream itself must be examined accurately, for…the outcome is altered by the least addition or omission, so that if anyone fails to abide by this, he must blame himself rather than us if he goes wrong.” [3]

While Artemidorus on occasion might have been able to work out some causal relationships in direct or theorematic dreams, he could not really provide a key to interpret figurative dreams. We now know it is so complicated that it still remains elusive two millennia later, but we can laud the logical approach Artemidorus was attempting. He was seminal in believing that every dream is unique to the dreamer and that waking life influenced dream life. He also tried to verify at least 95 dream outcomes he wrote about in order to be as scientific as possible, which make him appear very modern in his “systematic” outlook. [4]

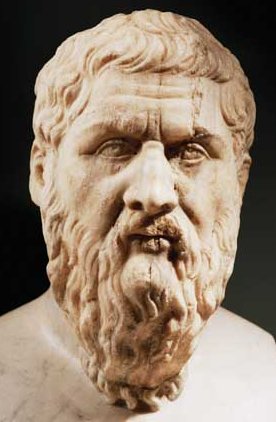

Although other civilizations contributed to the forefront of the development of psychology, much of their contributions were lost through the lack of written transmission. Plato, Aristotle’s teacher, developed insights into the human mind. He developed the Theory of Forms in which it was stated that the psyche defined the mind and the soul. With the Theory of Forms, Plato then developed a framework of human behavior as he attempted to learn and study how humans reason and how impulses are developed.

Plato’s Republic Book 4 theorized what Plato developed as three interconnected parts of the Tripartite soul (psyche). First, logistikon was the intellect or part of the mind as the seat of reasoning and logic. Second, epithumetikon was the appetitive part of the soul focusing on base desires. Third, thumoiedes was the emotional part of the soul or mind that dictated feelings. The thumoiedes also invoked and enforced logistikon to govern desires and appetites of the epithumetikon, in some function possibly parallel to what some have later called will. According to Plato, the healthy mind maintained a balance between the three parts. For example, for Plato the appetitive part of the soul seeking base desires for food and drink should nonetheless be governed by the other two parts, intellect or logistikon and emotions or thumoiedes. [5] Even today we identify that organ of the chest – which we now know is tied to our immune system – where the Greeks thought emotions were felt, still named the thymus in a sense after Plato.

Comparatively, Plato’s theory anticipates the model of Whole Health that is currently used by many therapists. The basis is similar to Plato’s logic in that the whole person must be treated; treating one symptom will not alone cure the individual’s mental malaise.

To paraphrase Plato elsewhere, his Phaedrus suggests our soul is like a chariot “driven” by two horses, the horse of passion and the horse of reason; the horse of passion is needed to move us toward our desires but the horse of reason examines and qualifies those desires, honing desire by a sense of what is right.[6]

Plato’s focus on examining human behavior to gauge what internally “drives” it also parallels Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), currently used as one goal-oriented treatment model in mental health aimed at changing how thought impacts behavior in dysfunctional emotions and maladaptive behaviors such as anxiety or mood disorder, among others. Only one working example is that CBT has even been strongly connected to healing eating disorders and is a forerunner in treating anorexia and bulimia, in a sense parallel to Plato’s theory of exercising self-control through internal change. [7]

Greek doctors were trying to find treatment and solutions to medical issues just as researchers do today. But because our understanding of chemistry and brain physiology is much more advanced and detailed, mental health as a holistic approach was significantly different than it is today. Although not limited to psychological matters, even our word for “therapy” derives from the Greek word therapeia, which eventually came to mean in ancient Greece “a medical or surgical treatment or cure”. [8] Galen (ca. 129-210 CE) was another Greek doctor, in fact, the imperial physician to the Emperors Marcus Aurelius, Commodus and Septimius Severus. Among over 600 medical treatises, Galen wrote much on psychological maladies (along with dream diagnosis) and also thought of himself as a philosopher – he wrote “the best physician is also a philosopher” – because of his experience as one who dealt with mental as well as physical malady, strongly believing in some psychosomatic connections from empirical experience. He once described a stressed-out patient who tossed all night, dreaming and worrying whether Atlas the Titan could hold up the sky (and the world in it) if this Titan got sick. Galen called this a case of dysthymia – a severe case of depression as a dysfunctional expression of maladjusted desire and will – and he believed that mental and emotional stress could cause physical sickness, especially as he followed Plato in his own “anatomy of the soul”. [9]

Although the external template of life may appear different than in antiquity, the basic body and psychology of human beings has not changed. Until recent history, people traveled by slower and more sedate modes. Communication was either by word of mouth or completed in the transmission of paper or scrolls when dissemination of information was controlled by limitations not encountered today. Our modern world may not really be any “busier” or more filled with activity, nor is the actual physical metabolism of life necessarily accelerated – after all a day is still only 24 hours long – but there is a glut of information with a faster rate of transmission of information that has increased exponentially. By gaining so much technology, we may have lost something in human transmission in that we may not take the same time to carefully read or study what our ancestors did only a few generations past because of the sheer volume of material now available. Perhaps it could be stated that the template of our world, of life, has changed. It is likely, however, that people and the individual human psyche have not necessarily changed.

Family trauma for weeks during severe illnesses cause intense grief and emotional stress. But in Ancient Greece, we can assume that individuals and families probably experienced similar emotions during a life crisis. Even our modern medical knowledge cannot simply alleviate fear or grief. Stress in today’s world may not be exactly ignited by the same causes, but nonetheless, the physical process that the body goes through in a stress event is and was the same. The adrenal gland kicks in, cortisol is released and we go into a “fight or flight” mode. In antiquity the stress reaction may have had different causations but individuals experienced stress and their bodies went through the same physiological response to the stress. Wars and battles were fought differently, but the process of how individuals responded to the stress was almost certainly the same as it is today, even if our physical stresses themselves have changed: we may not face a lion or dire wolf but our physiochemical and emotional response to an immediate threat or danger involves the same chemical triggers and other physiological change like endorphin neurotransmitters.

So are we that different from the Greeks millennia past? Again, the template of how the world looked in that era compared to today’s world in terms of social and political structure, language, modes of communication and other external stimuli may have been considerably different, but human beings respond internally in much the same ways. However our perceptions differ, the material body and the emotional and cognitive person (much of what Greeks called the psyche) have many of the same tensions as today. We are most likely not very different in the realm of mental health realities of what we experience relative to our ancestors. Even if they did not necessarily combine the two words as we have from their language, the Greeks had both the word for the “soul”, psyche, and a word for “healer”, iatros; with ancient practitioners like Artemidorus, Galen and Asklepian doctors engaging in some forms of “soul healing” we could recognize today.

Notes:

[1] For the bridging between ancient and modern also see C. A. Meier. Healing Dream and Ritual: Ancient Incubation and Modern Psychotherapy. Daimon Verlag, Einsiedeln, Switzerland, 2012 ed. (a different Northwestern University Press earlier edition in 1967); for one of the most representative or comprehensive studies that range on Asklepian topics, see Louise Cilliers’ editorship of Asklepios: Studies on Ancient Medicine, Acta Classica Supplementum 2, 2008, Bloemfontein, Classical Association of South Africa.

[2] Artemidorus, Oneirocriticon I. 1.2. Robert J. White tr.

[3] ibid., I.1.9

[4] Robert L. Van De Castle. Our Dreaming Mind. Ballantine Books, 1995, p. 68.

[5] Plato, Republic Book 4.436 & ff.; also see Charles Siewart . “Plato’s Division of Reason and Appetite.” History of Philosophy 18.4 (2001) 329-52.

[6] Plato, Phaedrus 246a-b.

[7] R. Murphy, S. Straebler, Z. Cooper and C. G. Fairburn. “Cognitive behavioral therapy for eating disorders.” Psychiatric Clinics of North America (Elsevier) 33.3 (2010) 611-27.

[8] Henry G. Liddell and Robert Scott. A Greek-English Lexicon, Oxford, 1996 ed., 792-3.

[9] R. J. Hankinson. “Galen’s Anatomy of the Soul.” Phronesis 36.2 (1991) 197-233; also noting Prof. Susan Mattern’s invited lecture at Stanford University Classics Dept., May 2009 on “Emotions in Galen”.

**********************

Editor’s Note: Laura Rehwalt, M.A. is licensed as LMHC (Licensed Mental Health Counselor) and therapist.