By Andrea M. Gáldy –

Whether one likes dogs or not, the current exhibition Treue Freunde: Menschen und Hunde (“True Friends: Humans and Dogs”) at the Bayerische Nationalmuseum in Munich is a must-see. It charts the cultural history of the relationship between humans and dogs back to the earliest times when tame wolfs or early dogs started to share our lives, food and accommodation (Exhibition catalog, pp. 34-41). This long and symbiotic bond between humans and canines turned dogs into pets and, eventually, into family members few of us can do without. While it is difficult to pinpoint the exact start of this wonderful friendship, there are good arguments to date it to a period up to 40,000 years ago. Just recently the remains of a remarkably well preserved two-months-old puppy was found in the thawing permafrost soil of Yakutsk; the pup lived c.18,000 years ago and scientists are still trying to figure out whether they are dealing with a wolf or dog

(https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/02/science/frozen-puppy-found-russia.html).

The exhibition presents twelve particular themes from this shared history, during which dogs became all things to all men and women – a being onto which human needs and requirements have long been projected. Over 200 works of art, consisting of paintings, sculptures as well as graphic works and photos, are displayed and complemented by a video at the end of the show. A dog may be a status symbol, portrayed next to the aristocratic owner and wearing splendid and fashionable collars (Fig. 1 Mastiff with Pup, painting by Johann Georg Waxschlunger (?), Munich, early eighteenth century, oil on canvas, Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, © Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, cat. 12.4). Today, they are fashionable accessories of celebrities, film stars and politicians (Fig. 2 Uschi Ackermann and Pug Sir Henry, Gustl Vogl, Munich, ca. 2015, digital photo, © Uschi Ackermann, Munich, photo Gustl Vogl, Munich, cats. 2.18 and 10.12).

Nonetheless, Sir Henry Ackermann-Käfer who died of cancer in 2018 (pp.74-77, cats. 12.22 and 12.23) became a celebrity in his own right. His life and personality led to his owner’s social engagement for the benefit of dogs and humans in a project called “paw in handâ€.

Dogs are frequently shown in paintings or on tapestries displaying hunting scenes (Fig. 3 Hunting Dog and Hare, Johann Christian von Mannlich, Zweibrücken, 1773, oil on canvas, Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, © Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, photo Bastian Krack, cat. 6.6). In these roles, dogs contribute to the visualisation of character traits humans wish to convey, such as power, wealth, faithfulness etc. Nonetheless, the faithful partner in the strong but unequal relationship between dogs and humans is all too often the canine member who pays for being kind and loving by being exploited as a working dog and even tortured and killed.

(Fig. 3 Hunting Dog and Hare, Johann Christian von Mannlich, Zweibrücken, 1773, oil on canvas, Bayerisches Nationalmuseum

The exhibition thus traces dogs’ lives and careers in our world, opening with a presentation of a work of literature, in which the famous German writer Thomas Mann created a monument to his dog Bauschan. Herr und Hund (1918) attests to the close relationship between Mann and his dog, their shared life and walks in Munich, actually in the Museum’s neighbourhood (cat. 1.1).

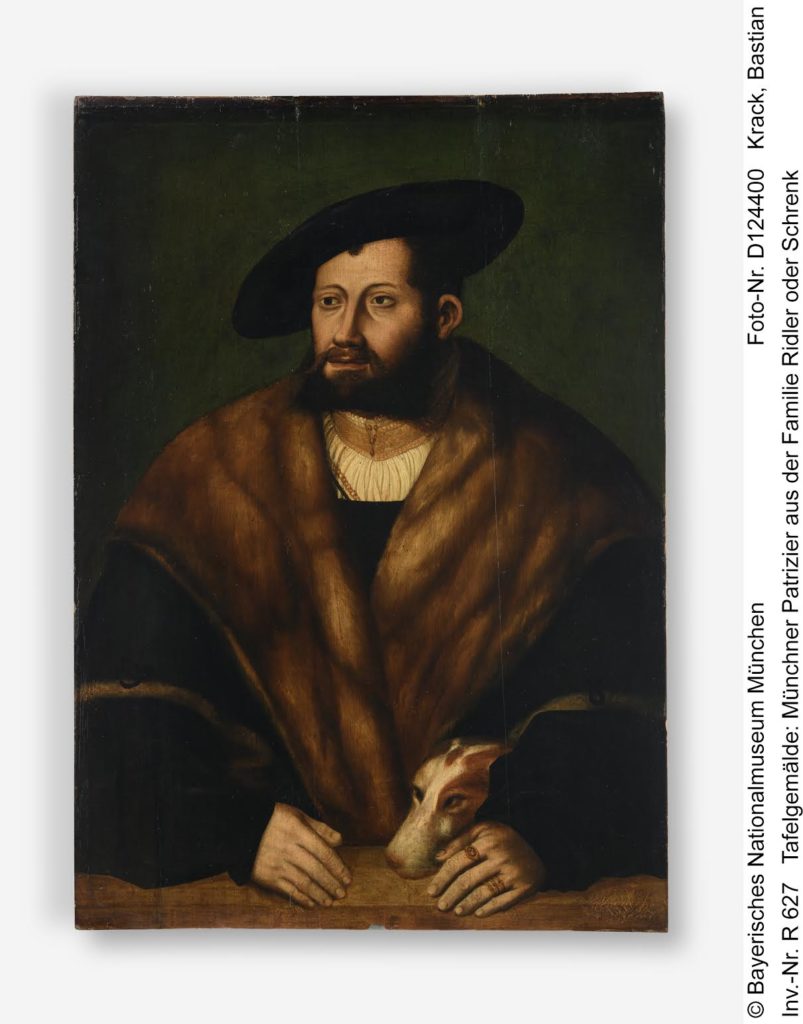

Related parts of the show deal with the mutual attraction between dogs and humans as well as the repulsion dominant in many cultures that see dogs merely as working animals and a source of food and clothing rather than pets living in the family and sharing our beds (Fig. 4 Big Dog in a Big City, Amit Elkayam, New York, 2018, digital print, © Amit Elkayam, New York, cat. 4.25). In the West, dogs are now mostly seen as friends and companions, while particular breeds still carry a connotation of wealth, rank and even power (Fig. 5 Gabriel Ridler, Hans Schöpfer der Ältere, Munich, 1532, oil on spruce, Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, © Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, photo Bastian Krack, cat. 4.4).

Fig. 5 Gabriel Ridler, Hans Schöpfer der Ältere, Munich, 1532, oil on spruce, Bayerisches Nationalmuseum

After all, many of us remember the dogs of Macron and Putin (cat. 5.17) attending political meetings and Obama jogging along the corridors of the White House in the company of First Dog Bo (cat. 2.17). Since dogs not only work for us but also help our emotional well-being, they have become part of literature, myths and legends; see Ulysses being recognised by his faithful dog Argos on his return from the Trojan Wars (cat. 4.2). Dogs play with us and entertain us, not always in ways that are good for them (e.g. dog fights and races). Particular breeds have become so fashionable that selective breeding caused defects that will mean live-long health issues, for example breathing difficulties for pugs. In especially serious cases the combination of inbreeding and ill-treatment is known to call forth increased aggression that may end with attacks including the owners’ deaths; think of Staffordshire Bull Terrier Chico driven to kill his owners in 2018 by a history of pain and neglect.

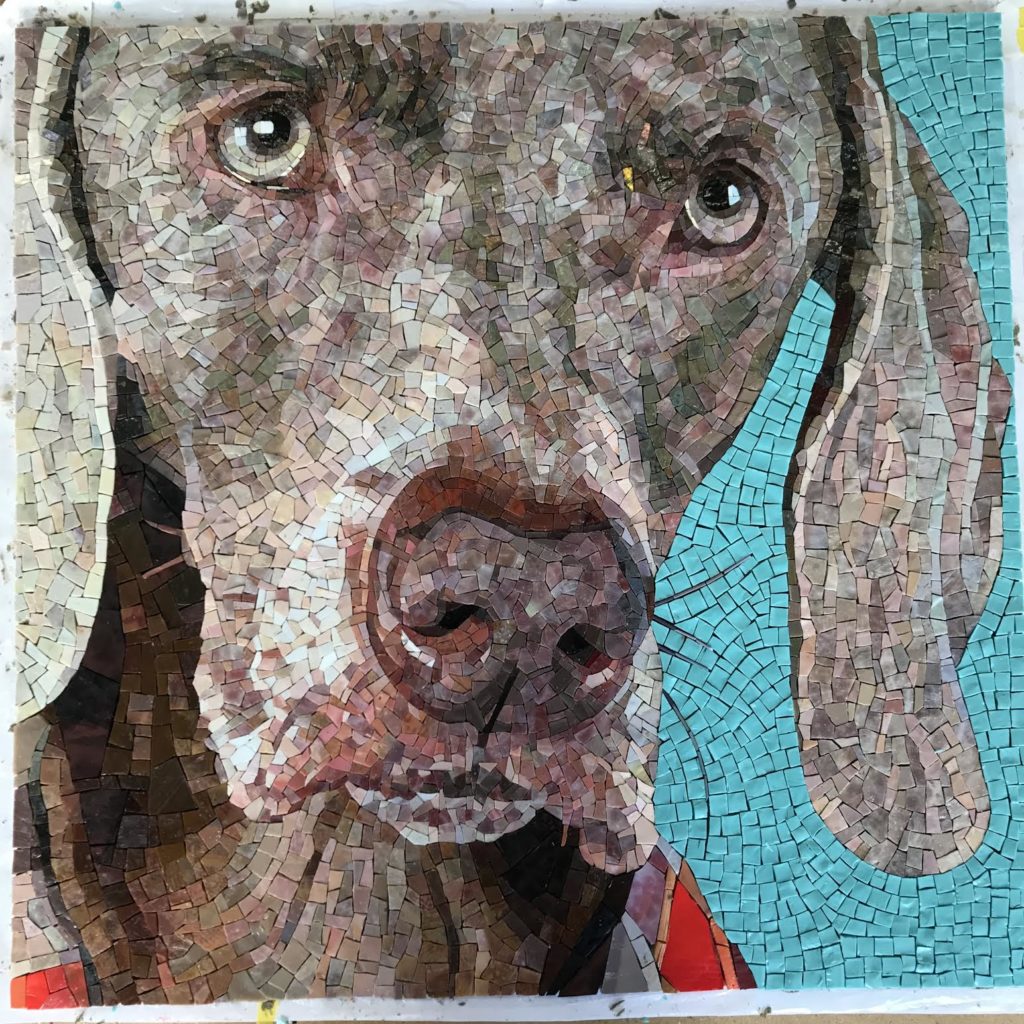

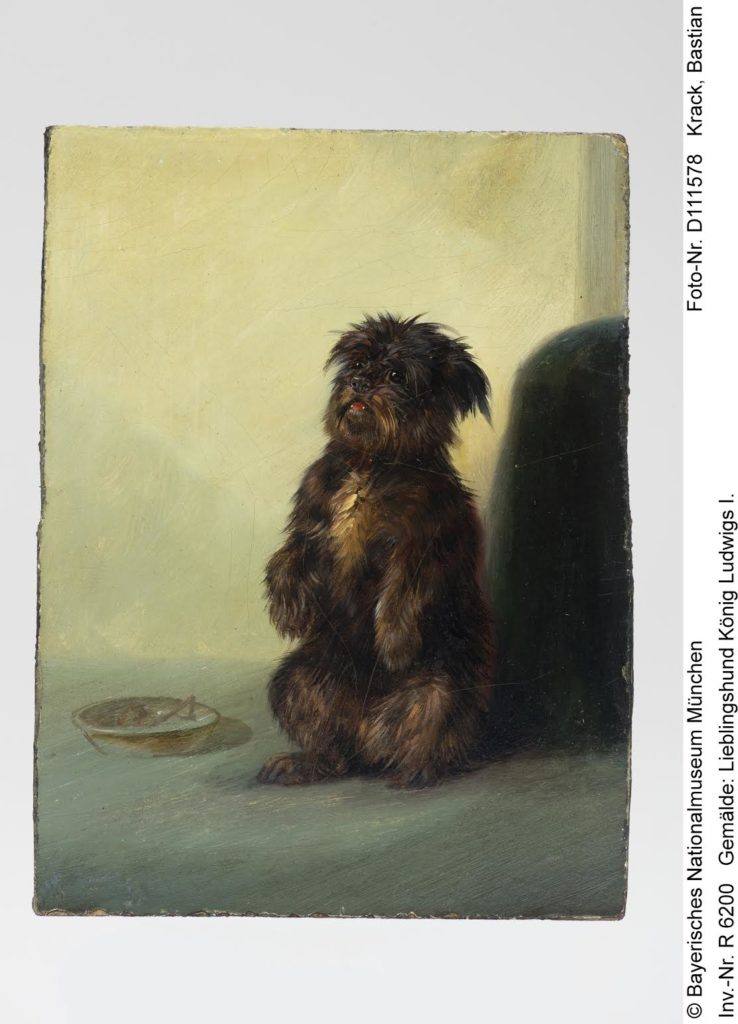

Although dogs may not be our closest relatives among mammals, they managed to become so like us (and we so like them) that they read our facial expressions and imitate them. Indeed, a major difference between wolf and dog is the ability to raise the levator anguli oculi medialis and thus the inner eyebrow in a way that gives them puppy dog eyes and makes it easier to communicate with humans who find it hard to resist (Fig. 6 Stationary Figures (detail), William Wegman, sketch, Mayer’sche Hofkunstanstalt, Munich, made for MTA Arts & Design, Munich/New York, 2017/18, © MTA Arts & Design, New York, cat. 10.13). Indeed, their manipulative looks and behaviour at times make them seem a more appealing furry version of humans and as a result many of us become so very attached to our canine companions that we seek to preserve at least their memory by means of a burial (cat. 4.26) or a fetching portrait (Figs 7 and 8 King Ludwig I’s favourite Dog, Munich, ca. 1850, oil on cardboard, Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, © Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, photo Bastian Krack, cat. 12.9; Empress Catharine II’s favourite Dog, Johann Joachim Kaendler, Porzellanmanufaktur Meißen, ca. 1770, porcelain with over glaze, Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, © Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, photo Bastian Krack, cat. 12.7). Today, there is also the possibility to clone your dog and fall in love with his or her genetic copy.

While the exhibition leads you through centuries of material culture created as a consequence of dog-human cohabitation from antiquity to the present day, it only occasionally dwells on the negative aspects. Most exhibits delight with their beauty and quaintness and, if you like dogs, confirm that they are the only true crown of creation. It takes the very well-done and interesting catalogue, unfortunately solely available in German, to give you the fuller story. Mann’s liking for dogs and his love for Bauschan were not in keeping with today’s tenets for animal welfare (pp. 22-33). His dogs were beaten, discarded and put down without compunction. After all, western attitudes towards dogs changed but recently and butchers offered meat from freshly slaughtered dogs until the later twentieth century. In the 1980s, coats made from so-called “gaewolf†pelts, also labelled animal by-products or Asian jackals, were a cheap and fashionable luxury (cat. 3.8). The dog-fur coat seems to have been removed from the exhibition in response to protests but, of course, it would be much better to remember how popular they were at the time and how many dogs had to die for them. Amulets made from dog teeth (cat. 3.7) and dog fat (cat. 3.6), axungia canis, were appreciated for magic or medicinal properties until the nineteenth century at least. Before then, dogs played a role in capital punishments (pp. 58-60), for example in the execution of Jews (cat. 3.3). Dogs are still being used for experiments, in particular for new medicinal products; few of them acquire any fame or receive our thanks for the service provided at the cost of their health and lives. An exception was the Russian dog Laika who died in 1957 as a victim of the Soviet space programme and whose end caused massive protest in Western Europe (cat. 6.24).

With Treue Freunde the Bayerische Nationalmuseum created an unusual exhibition that is well worth your visit. Here, the shared history and material culture come together to make one appreciate the closeness of dogs and humans and may make visitors reconsider our relationship to the animal kingdom at large.

Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Munich

29 November 2019 to 19 April 2020

Treue Freunde: Hunde und Menschen

https://www.bayerisches-nationalmuseum.de/index.php?id=1169

Frank Matthias Kammel, ed. Treue Freunde: Hunde und Menschen. Munich: Bayerisches Nationalmuseum/Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2019.