By Patrick Hunt –

Every year for the past five years, after fieldwork in the Alps I come down to Torino (Turin) in August. Following Hannibal’s route, I come not to conquer the Taurini like Hannibal but instead to be conquered by Torino, so famous for its slow food – one should always look for the decorative snail motif on culinary establishments – among other equally mesmerizing cultural treasures. Other than gourmandaise, one of the world’s best museums is in Torino, properly named Museo delle Antichita Egizie, but generally abbreviated as Museo Egizio. One of its near unique hallmarks is that it is the only museum other than Cairo’s entirely devoted to Egypt.

The museum’s imposing red brick edifice takes up a whole block in the heart of the old city between Piazza San Carlo and Piazza Castello, also easily connected to the Biblioteca Nazionale and the Museum of the Risorgimento, each facing the Piazza Carlo Alberto only a block or so away. One almost expects to view the domed head of the alchemist Fulcanelli over a tome while browsing esoterica in academic bookstores nearby here in Torino’s intellectual center.

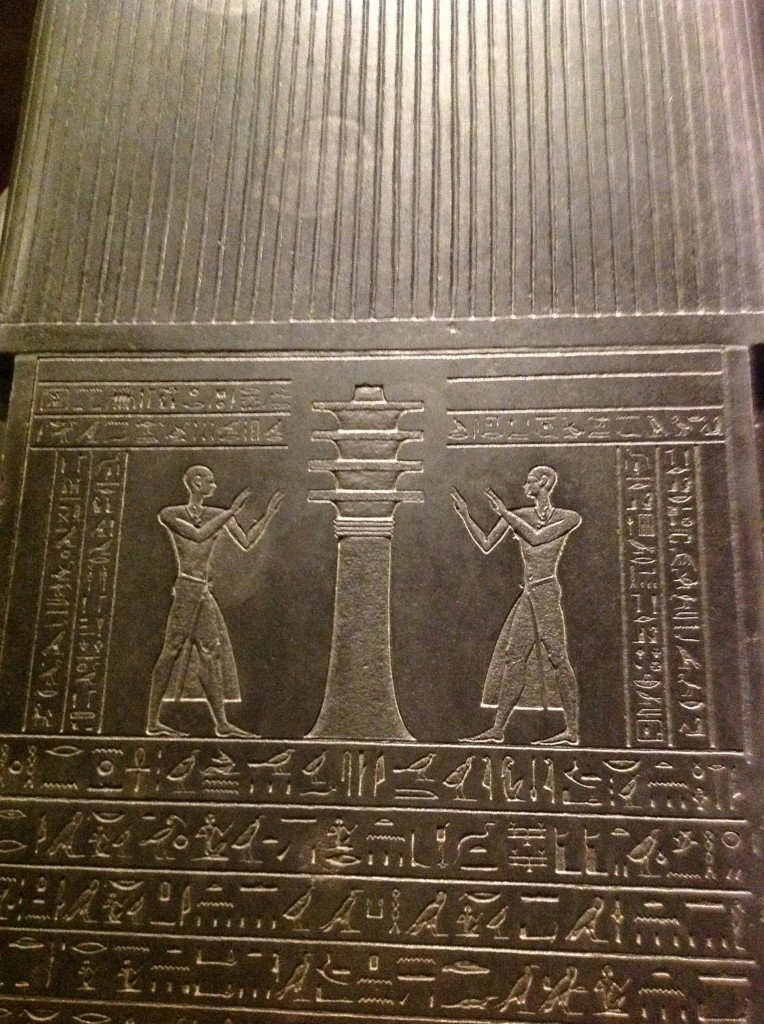

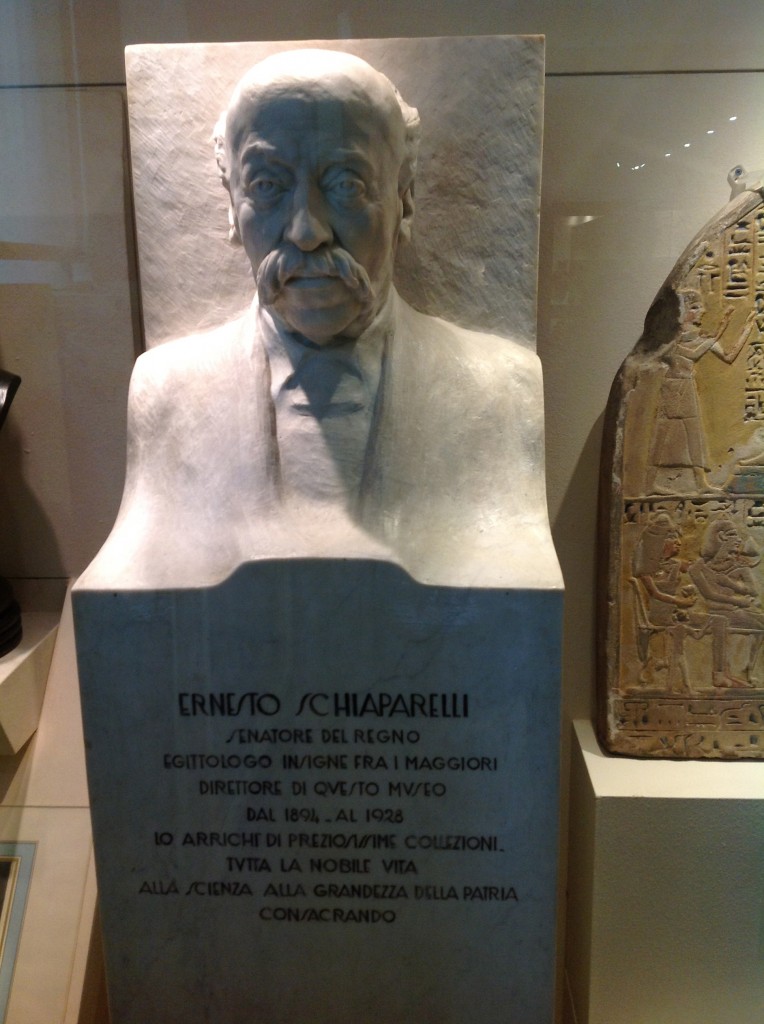

The Egyptian Museum was founded in 1824 under King Carlos Felix (1765-1831), king of Piedmont-Sardinia and of the House of Savoy,[1] and assimilated over 5,500 objects assembled by Bernardino Drovetti (1776-1852), colorful Piemontese diplomat, judge and antiquarian appointed by Napoleon to Egypt as French Consul.[2] Jean-Francois Champollion of Rosetta Stone fame studied this huge Egyptian collection in 1824, noting that the road to Memphis and Thebes passes through Turin. While many of the collections date back to the nineteenth century, material from excavations between 1900-35 add to the volume of artifacts. Ernesto Schiapparelli, Egyptologist and museum director between 1894-1928, brought many of the collections together and complemented by his own archaeological work in Egypt. Schiaparelli is most famous for finding the tomb (QV66) of Queen Nefertari, wife of Rameses II the Great in the Valley of the Queens in 1904. [3] One of the notable small room exhibitions is of Schiaparelli’s work at Gebelein and Asyut in the first half of the twentieth century, especially the wooden statues, granary models an related finds.[4] The necropolis artisans’ village, Deir el-Medina, is also a source for many of the most beautiful objects form Egyptian daily life.

The Tomb of Kha (Royal Architect) was discovered in 1906 by Schiaparelli and its excavated assemblage of 506 undisturbed objects is on display from the lives of Kha and his wife Merit, circa 1400 BCE. One of the most sanguine displays is of food preserved from tombs, especially grain and other comestibles that have survived in Egypt’s arid climate. After years of conservation, the 8 meter long papyrus of the Book of the Dead (“Book of Going Forth by Day”) of Tasnakht has been visible since July of this year, now shown in Room II. Other papyri forming a corpus of similar manuscripts include those of Rattaui, Hor Padikhonsu, Padiamon and Tasheritkhonsu.

Two of my favorite objects in the museum, as I view them dutifully on my annual Turin pilgrimage – include a c. 1200 BCE, XIXth Dynasty, Third Intermediate Period singular small painted limestone ostracon of a lithe dancer seemingly so flexible as to bend nearly completely over. Her hair touches the ground as she contorts backward with a proud bosom heavenward, practically a reversal of the sky goddess Nut’s downward earth-nourishing bend. In fact, her hair is natural and not a wig, as in so many tomb paintings. She probably derives from a Deir el-Medina tomb artist’s playful sketch of entertainment and may even be a fantasy sketch, but she is executed at the highest level of skill and imagination.

Also perhaps the world’s most famous global cartographic relic is on permanent display: discovered around 1820 by Bernardino Drovetti in Deir el-Medina, the Turin Papyrus Map (12th century BCE) showing nascent geology of hard bekhen stone, quartz and gold mines in Bir Umm Fawakhir and related structures in the Wadi Hammamat, all with a commentary in hieratic text. [5] Auriferous geologists today know a secret that seemingly Ancient Egypt first noted: gold is found at the junction where quartz and serpentine meet (as in California’s Gold Rush where Sierra granite plutons are in contact with serpentine along what is now Highway 49); serpentine is naturally the state rock of California. Painted in a range of colors and with a length of 2.82 meters and a width of 41 cm, this map demonstrates that ancient Egypt could differentiate stone masses during the quarrying expeditions of Rameses IV. Both of these objects are very close to each other and are not to be missed in Room V despite being in the sequence of the last galleries upstairs. Room VII also displays caricatured animal mummies of crocodiles and cats as well as feline bronzes of Bastet, the cat goddess. A box for ushabti statutettes, one of many in the collection – the ushabtis themselves made of bronze, faience, wood or even ceramic, each with his or her own name – demonstrates how important it was for even tomb workers in the afterlife to be properly housed. The one in the photo below is from the XXI-XXII Dynasty and has seated Isis and Nepthys, goddess wives of Osiris, painted on the side.

The museum’s extensive chronological collections range from Predynastic Egypt (Naqada Culture 4000-3200 BCE) including slate palettes and Naqada I pottery with its distinctive black rims from oxygen reduced firing, all the way through time to Romano-Egyptian hybridization of gods and ultimately to Coptic Egypt with fifth and sixth century CE textiles.

Perhaps the grandest gallery honor goes to the statuary collection of over 50 colossal stone pieces in basalt, Aswan pink granite, sandstone, limestone, greywacke, including images of Thutmose III, Amenhotep II, Tutankhamen, Horemheb, Rameses II, Seti II, among other rulers and high nobles. Gods are also well represented, with Amun, Hathor, Ptah and over 20 statues of the goddess Sekhmet on display. The brilliant design with dark mirrors offsetting the sculptures was by Dante Ferretti, 2005 Academy Award winner for design in Martin Scorsese’s Aviator film. This dramatic gallery is a magical amalgam of ancient art with canny modern presentation.

Turin’s Egyptian Museum is now administered and funded by the generous Fondazione Museo delle Antichita Egizie di Torino in cooperation with the Soprintendenza per Beni Culturali e Archeologica di Piemonte (Superintendence for Archaeological Heritage of Piedmont). The Gli Scarabei, an association of private sponsors also funds vital conservation projects, like the recent Tomb of Kha work, for which the association raised 80,000 euros. Professor Rocati Alexander has recently been named by the Ministry of Heritage and Culture as Chairman of the Scientific Committee of the Museum Foundation and his tenure is paying off with renewed precise conservation efforts like what is now being innovatively done for papyri, textiles and wood objects. The museum’s inexpensive entry fee (3.50 euros to 7 euros) to view the entire museum is well worth every cent. In fact, it is such a bargain that visitors will have added incentive upon exiting for a two minute stroll to visit the nearby famous Grom store for the best sorbetto gelato in Italy to cool off from realistic visions of an arid Egyptian sojourn with a precious global collection.

Notes:

[1] Roland Sarti. Italy: A Reference Guide from the Renaissance to the Present. Facts on File/ Infobase Publishing, 2009, 199-200.

[2] Brian Fagan. Rape of the Nile: Tomb Robbers, Tourists and Archaeologists in Egypt. New York: Basic Books, 2004, 58-9, 61-5, 81-8 & ff.

[3] Joyce Tyldesley. Chronicle of the Queens of Egypt. London: Thames and Hudson, 2006, 146-52.

[4] Angela M. J. Tooley. Middle Kingdom Burial Customs: A Case of Wooden Models and Related Material. vol. 1. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Liverpool, 1989, esp. Asyut material, 351-2.

[5] James Harrell and V. Max Brown. “The World’s Oldest Surviving Geological Map: The 1150 BC Turin Papyrus from Egypt.” Journal of Geology 100.1 (1992) 3-5 & ff.