By Patrick HuntÂ

After more than three centuries, Henry Purcell’s (1659-95) sole opera Dido and Aeneas remains a treasure. Considered the greatest operatic achievement of 17th century England [1] and the first great English opera, [2] even though a performance only takes little more than an hour, it is often justified as holding its position as the finest English opera ever written until the 20th century. [3] Despite the opera’s mostly forgotten status from 1700 to the 1890’s when it was revived by the Royal College of Music at the Lyceum Theatre in 1895, who could ever forget the haunting aria, Dido’s Lament, “When I am Laid to Rest� More on this incomparable aria follows shortly. The earliest full score of Purcell’s music for the opera is late, circa 1750 from a Bodleian Library copy in Oxford. [4]

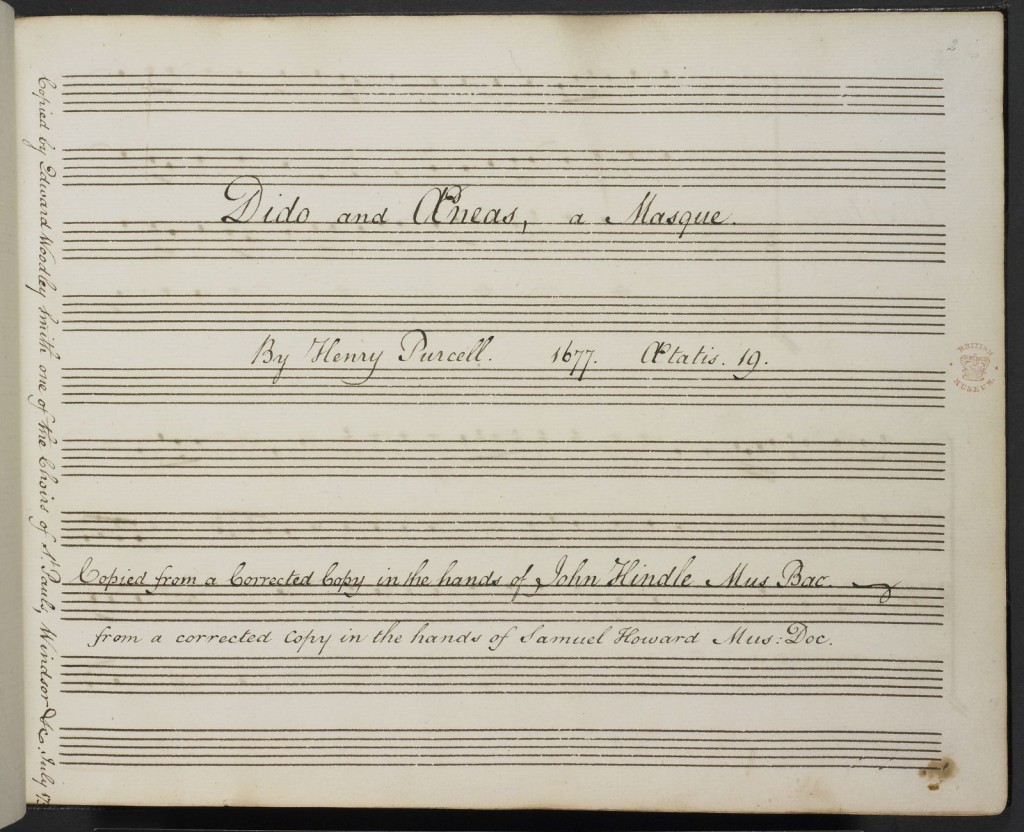

Although arguable, while Purcell was clearly influenced by his master John Blow, the question of how much Dido and Aeneas owes to Blow’s own 1683 opera Venus and Adonis remains to be seen. Debate continues because while traditionally thought to have premiered at Josiah Priest’s school for girls in Chelsea in 1689, good arguments for Dido and Aeneas’ earlier composition and performance in 1684 have been proposed and debated, with some claims of even having been written as early as 1677. [5] The storyline of Purcell’s opera is roughly taken from Virgil’s Aeneid, Book 4, as briefly discussed below.

Notable too is the libretto by Nahum Tate (1652-1715), himself a Poet Laureate of England from 1692-1712, [6] and famous hymnist-poet, for example, of the circa 1703 carol “While Shepherds Watched Their Flockes.†Tate’s libretto for Dido and Aeneas was adapted from his own 1678 masque, Brutus of Alba, or The Enchanted Lovers. Tate was often vilified for his “mutilations and tortures†of Shakespearian plays like King Lear and Richard II, and while attacked by Richard Addison and Alexander Pope for his textual liberties with Shakespeare – already holy ground – no less than Samuel Johnson came to Tate’s defense on occasion, perhaps to be contrarian but just as likely because Tate’s tragic adaptations also had some merit of their own, like the later Charles Lamb’s Tales from Shakespeare. [7]  Tate was certainly recognized as a a celebrated poet and successful dramatist in 17th century London by royalty, his literary peers and theater-goers alike. [8]

Tate and his better-known poet contemporary John Dryden who translated Virgil’s Aeneid, collaborated on occasion, including in Absalom and Athitophel in 1682 and elsewhere in The Loyal General (1680). Both of these celebrated poets also wrote “Odes on St. Cecilia’s Dayâ€, Dryden’s 1687 poem receiving the greater, more enduring fame. [9] Given their collaboration, it must be Dryden’s Aeneid 4 translation that best informs Tate’s libretto. Comparisons of the Dryden and Tate texts, however, in the most dramatic moments shows they have little in common beyond plot highlights. This is best seen, for example, when Dido commits suicide (Act III of the opera, 4.642-705 in the lines of Virgil’s original epic Latin poem). In this tragic climax, the actual texts of Tate’s lyrics are clearly not derivable from Virgil via Dryden, and sometimes echo only the faintest of ideas of the mise-en-scène :

First Dryden:

“Then shalt thou call on injur’d Dido’s name:

Dido shall come in a black sulph’ry flame,

When death has once dissolv’d her mortal frame;

Shall smile to see the traitor vainly weep:

Her angry ghost, arising from the deep,

Shall haunt thee waking, and disturb thy sleep.

At least my shade thy punishment shall know,

And Fame shall spread the pleasing news below…”Â

Thus Dido prophesies that even before Aeneas goes to the Underworld in Aeneid Book 6 and while there on his journey, this scène noir is what he’ll find. Later in Dryden’s translation, Dido weeps to Juno and her Punic gods:

“…Receive a soul, of mortal anguish eas’d:

My fatal course is finish’d; and I go,

A glorious name, among the ghosts below.

A lofty city by my hands is rais’d,

Pygmalion punish’d, and my lord appeas’d.

What could my fortune have afforded more,

Had the false Trojan never touch’d my shore!”  [Dryden]

For comparison with Dryden, as well as Virgil’s own incredibly dark lyrics,  here is the most famous of Purcell and Tate’s collaboration in the aria lyrics of  “Dido’s Lament: When I am Laid in Earth†from Tate’s libretto:

“When I am laid, am laid in earth,

may my wrongs create

No trouble, no trouble in thy breast.

When I am laid, am laid in earth,

may my wrongs create

No trouble, no trouble in thy breast.

Remember me, remember me, but ah!

Forget my fate.

Remember me, but ah!

Forget my fate.

Remember me, remember me, but ah!

Forget my fate.

Remember me, but ah!

Forget my fate.â€

Without making any obvious borrowing of even a Virgilian-Drydenesque phrase, in the above text of “Dido’s Lament†Tate has tightly compressed Dryden’s Virgilian translation of several of Dido’s monologues into a highly distilled, emotionally powerful mournful lyric full of irony but stripped of all the venom against Aeneas.

Since he has elsewhere (Act II, Scene 1) invented sorceresses and witches in his libretto, characters who do not appear in the Aeneid, Tate is only loosely following Classical precedents. On the other hand, like Act II, Scenes 1 & 2, Aeneid 4:130-70 does indeed have a hunting scene with Aeneas and Dido and a cave where Venus brings the lovers Dido and Aeneas together by divine trickery. Tate’s messenger of the sorceress – disguised as Mercury – also hollowly imitates Virgil’s Mercury with both messengers’ commands from “Jove†for Aeneas to leave Carthage (Aeneid 4:220-75), thereby abandoning Dido. Finally, Tate’s Act III also parallels Virgil’s original contexts with both the harbor of Carthage (Aeneid 4:535-80) and the culminating palace scene with Dido’s suicide (Aeneid 4:642-705). Nonetheless, it is fair to say that Nahum Tate is a far more biblically than Classically-inspired poet.

One of the first pieces of keyboard music I learned to play was a Purcell ‘Hornpipe’, and I’ve never forgotten this delightful melody with its inverted second part and the austere but perfect counterpoint in this little gem. Although he also borrowed and adapted folk tunes, Purcell was a supreme melodist who created some of the best tunes in English music, [10] as his ‘Hornpipe’ and “Dido’s Lament” attest.

Thus, it is expected that I can hardly ever tire of the musical plangency of “Dido’s Lament: When I am Laid to Rest.†I can actually listen to recordings of it ten times in a row, either by the same soprano or by another, especially with its downward ground bass instrumental accompaniment in strings and/or keyboard. The song featured as a central highlight in the blockbuster BBC 1998 film version of Thackeray’s Vanity Fair 1998. My favorite recordings have included Dame Janet Baker’s, Leontyne Price’s, Jessye Norman’s, Rene Fleming’s, or Sarah Connolly’s interpretations, mostly mezzo solos. I seem to often prefer the richness of the young Leontyne Price recordings as most profound, but I also recently heard the non-operatic Alison Moyet’s version, and also found it stunning as an alto solo. Even though some “purists†could fault Moyet’s deeper interpretation as inauthentic and questionably Classical, perhaps it is as accessible as any piece of 17th music ever could be three hundred years after the fact. This is an eternal song that can color one’s dreams lifelong.

It is possible that Tate’s idea of a lament for Dido may also have been influenced by English biblical use of the Hebrew poetic form, the literary qinah, for example as found in the text of II Samuel 1 when King David mourns Jonathan’s and King Saul’s death by the marauding Philistines on Mt. Gilboa.[11]  Tate was certainly familiar with biblical texts, having poeticized Psalms and other texts, and his clergyman father Faithfull Teate (son Nahum changed his name’s spelling in 1677) had been a famous preacher and also a poet, both of them having graduated from Trinity College, Dublin, before moving back and forth to London. The qinah was a Semitic literary form, predating Hebrew in Ugarit, and if we can rightly expect Dido’s Punic descendants of Phoenicians to have had a similar lament as their ancestors it might not have been such an unlikely prescience for the biblically astute Tate to appropriate the biblical qinah lament form, although few before Bishop Lowth (1710-1787) had formally studied Hebrew poetry assiduously.

Whatever may be said of Nahum Tate’s liberties or weaknesses as his critics have claimed, his artful collaboration with Henry Purcell on this opera, and in particular this most haunting of arias (“Dido’s Lamentâ€) is as successful as any librettist-composer relationship in Classical music.

Notes:

[1] C. A. Price. Henry Purcell and the London Stage. Cambridge University Press, 1984; E. T. Harris. Henry Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas. Oxford, 1990.

[2]Â M. Kennedy, ed. The Oxford Dictionary of Music. Oxford, rev. 2nd ed. 2006, 699

[3]Â D. M. Randel. The Harvard Concise Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Belknap/Harvard University Press, 1999, 466.

[4]Â Â W. H. Cummings. Dido and Aeneas, Dover repr. 1995, x. There is another partial score copied by John Travers from 1720.

[5] Â B. Wood and A. Pinnock. ” ‘Unscarr’d by Turing Times’? The Dating of Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas.” Early Music 20.3 (1992) 372-90; A. R. Walkling. “The dating of Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas.” Early Music 22.3 (1994) 469-81. Note above image of a manuscript title page by the copyist hands of Hindle & Howard and claiming a date of 1677, very early indeed, which would certainly antedate John Blow’s 1683Â Venus and Adonis.

[6]Â Â B. Corman, “Nahum Tate”. The Literary Encyclopedia (2003).

[7]  technically Charles and Mary Lamb’s Tales from Shakespeare, circa 1807. My copy was published in 1964 by Paul Hamlyn in London. Although the genius twists of plots are Shakespeare, these 19th c. prose tales have a life of their own.

[8]  C. Spencer. Nahum Tate (Twayne’s English Author Series). Twayne Publishers, 1972.

[9]  D. Hopkins. “The London Odes on St. Cecilia’s Day for 1686, 1695 and 1696.†The Review of English Studies, New Series 45.180 (1994) 486-495.

[10]Â Â M. Adams. Henry Purcell: The Origins and Development of His Musical Style. Cambridge University Press, 1995.

[11]  Or likewise in Hebrew prophets like Jeremiah and the biblical book of Lamentations. Also see W. H. Shea. “David’s Lamentâ€. Bulletin of the Schools of Oriental Studies 221.14 (1976) 141-44, noting derivations from the Pre-Phoenician Ugaritic qinah form.

3 Comments